The Chariot of the Sun, 14th century BC, National Museum, Copenhagen, Photo Roberto Fortuna and Kira Ursem

From a Hellenistic king, to the guiding hand of da Vinci, amid 5, 000 years of sculpture

By James Brewer

Even the great Leonardo da Vinci had his disappointments. Credited with designing the prototype modern submarine, he shrank from pursuing the project when he realised its potential for military destruction.

Another grand design that was frustrated – as he turned his versatile and restless hands to painting, architecture, mathematics, anatomy, and civil engineering – was to see his major sculpture projects turned into reality.

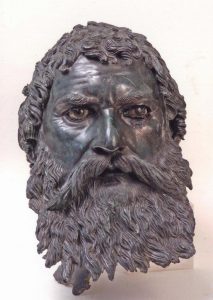

Portrait of King Seuthes III, Fourth century BC., National Institute of Archaeology, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia.

Although he loved sculpting from his early days, the closest work we now have to a sculpture by the quintessential Renaissance man was created, with his guidance, by one of his colleagues. It will go on show in September 2012 at the Royal Academy, London, in an exhibition entitled Bronze, which will cover 5, 000 years of artistry in that solid and enduring medium.

Leonardo was constantly at the shoulder of his fellow lodger Giovanni Francesco Rustici (1474–1554) who was working on monumental bronze figures that for nearly 500 years graced the north door of the Florence Baptistry. The ensemble St John the Baptist preaching to a Levite and a Pharisee which will be a feature of the Royal Academy exhibition, was commissioned in 1506. According to biographer of old Giorgio Vasari, while Rustici was fashioning the clay model for the group, Leonardo was making the moulds and preparing the armature, and up to the casting of the statues, never left his side; hence some believe that Leonardo worked at them with his own hand, or at least was a fount of advice.

Leonardo had told Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan, that he could build portable bridges, ships, armoured vehicles, and other war machines, and that he could execute sculpture in marble, bronze, and clay. In 1482, the Duke commissioned him to build a 7.3 metres high bronze horse in honour of his father. Leonardo got as far as making a full-size clay model, and even consulted cannon and bell makers on foundry techniques, but the bronze was never cast, for such metals were rather in demand at the time to build canons to keep the French army at bay. Leonardo’s sketches were eventually put towards a completed work – in 1999 for an American enthusiast, when bronze versions were installed in Milan and in Michigan.

The Pharisee, St John the Baptist and the Levite, 1511, Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore., Restoration with the sponsorship of the Association Friends of Florence., Photo Antonio Quattrone, Florence

In its show, the Royal Academy is to fill the main galleries with 160 bronze objects from more than 100 lenders, many of the pieces leaving their countries of origin for the first time. As an alloy of copper, tin, zinc and lead, bronze has an ideal resilience, and part of the exhibition will be devoted to the complex processes involved in making it – which have not changed much over the years, especially since the lost-wax technique became popular.

Among many outstanding pieces being shipped to London for the first time will be the early Hellenistic Portrait of King Seuthes III which has been on show in the National Archaeological Museum, Sofia, since only 2004. This commanding, luxuriantly bearded bust has never featured strongly in any survey of classical art. Some people believe that the severed head must represent a defeated enemy (the king rebelled against Alexander the Great), but Professor David Ekserdjian, who with Cecilia Treves curated Bronze, doubts that. He said that the head of the Thracian ruler was similar to that found on coins of the time, it came from his tomb, and was therefore a statement of his importance.

Spider IV, 1996., Louise Bourgeois, Collection the Easton Foundation., Courtesy Hauser & Wirth and Cheim & Read. Photo Peter Bellamy. Copyright Louise Bourgeois Trust.

From the 14th century BC we shall see the magnificent bronze and gold Chariot of the Sun lent by the National Museum of Denmark. Ancient Greek, Roman and Etruscan bronzes will sit close to works by Rodin, Picasso and others of the modern era – and one of Louise Bourgeois’s spiders, large enough to terrify any arachnophobe.

The exhibition will run from September 15 to December 9 2012.

1 comment

a wonderfully concentric selection of bronzes and a medium that always excites us.