Cutting Edge: Modernist British Printmaking on show at Dulwich Picture Gallery

By James Brewer

A wonderful surprise awaited Gordon Samuel in summer 1983 as he began stock-taking at the Redfern Gallery in Cork Street, London, where he was a director and partner. Opening a dusty white drawer, he came across a neglected batch of linocuts produced some 60 years earlier.

They were the type of prints and posters in designs that “sang” with rhythm and vitality – some of the artists had been accomplished musicians, and many shared in the 1920s and 1930s craze for jazz or loved going out to classical concerts. Art historian Hana Leaper refers to a “syncopation of colour” redolent in the confident, exhilarating style of the images.

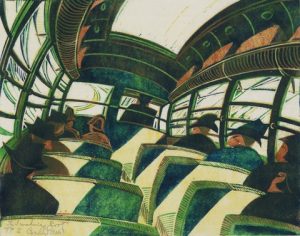

Prominent among the works rescued from obscurity at the Redfern was the 1934 print The Tube Train by Cyril Power, a characterisation of a carriage congested with stoically suffering commuters that many years later chimes with the slog of travelling on public transport at peak times.

Recovering the cache led Gordon Samuel to promote the artform widely and seek out similar treasures. From a chance meeting with Power’s son, the dealer learnt that a cousin of the artist had for decades stored six precious linocuts on top of his wardrobe. There was an international surge of interest in the genre which led to examples changing hands for six-figure sums.

Now, Dulwich Picture Gallery is helping re-popularise these joyous works in an exhibition guest-curated by Mr Samuel, who in 2004 founded the Osborne Samuel Gallery with Peter Osborne. The partners’ Mayfair gallery is described as the leading international dealership in the linocuts of the Grosvenor School of Modern Art, which was the font of a brief but intense period of dynamic block printmaking. Dulwich calls its exhibition Cutting Edge: Modernist British Printmaking with the sub-title Ten artists. One revolution.

The Grosvenor School which attracted students from as far away as Australia to become a leading force in modern printmaking was founded in 1926 at 33 Warwick Place, Pimlico, by the Scottish wood engraver Iain Macnab. There were no set courses, and to enrol, you did not need an exam qualification – you bought a book of tickets for the classes you wanted. Students eagerly learned from each other, in workshops in the basement.

The practitioners revolutionised linocut by taking fully on board the machine age and urban modernity. They “made waves” both in terms of rendering accessible their subject matter and in variously flowing and regimented line they employed. Here are mesmerising – sometimes in the optical sense of the word — works by the influential teacher and artist Claude Flight, and nine of his leading students including Cyril Power, Sybil Andrews, Lill Tschudi, William Greengrass and Leonard Beaumont.

Claude Flight lectured on the art of lino-cutting, and Cyril Power on architecture. Sybil Andrews in addition to studying was the school secretary. It was truly a “cutting edge” explosion of talent.

Notwithstanding the glory of an inaugural exhibition of British linocuts at the Redfern Gallery in 1929 and exhibitions overseas, their brilliance did not sustain public and commercial interest, and members of the original group already having dispersed, and with the disruptive effect on the arts of the outbreak of World War II, the institution closed in 1940.

These works – often on fragile, thin Japan paper – were largely forgotten until the 1970s. The Dulwich display of 120 prints, drawings and posters ensures the genre will continue to be celebrated well past the centenary of their production.

These “joyful and optimistic” linocuts were most famously used on posters – to which they lent themselves perfectly – by the predecessors of London Transport, in classic advertising campaigns urging the public to make the most of the Underground and private and public bus services.

In a few strokes of the blade, the artists could encapsulate the excitement of Wimbledon tennis, cricket and rugby matches, speedway and the Epsom Derby. The designs were sometimes spare, but were figurative and accessible, unlike the output of some modernist movements of the early 20th century. The economy of their outlines might well have been enjoyed by followers of the Bauhaus school or Russian proponents of utilitarianism in construction and community living.

They brought modernism in art to a wide audience, and affirmative messages at a time of poverty and unemployment suffered by many.

For any London resident or visitor, the most fascinating rooms at Dulwich will be the two dedicated to transport in the capital.

Especially riveting is The Tube Train, a linocut from around 1934 by Cyril Power, and which spent several years in the dealership drawer. It has the tube carriage as a “cocoon” of behatted commuters on a packed District Line journey. What were known as F stock trains ran on the Underground from 1920 to 1963 with stops in Power’s home borough of Hammersmith. The wagons were mockingly nicknamed tanks because of their steel construction.

In the linocut, which in its careful draughtsmanship reflects Power’s training as an architect, most of the passengers seek distraction in their morning newspapers beneath the yellow glow of the electric lights, and at the far end of the carriage some hang on to the straps as the train sways and jolts.

One of the best-known images from the era is Power’s The Tube Station (1932). A crowded train whooshes away from the platform into the curved tunnel, a guard – in standard cap and double-breasted jacket – having just given the departure signal. The gallery shows the original blocks with colours that made the print.

Directly evocative of the 1930s are the original tube posters designed by Power and Andrews (working under the pseudonym of Andrew Power). The posters were commissioned by the far-sighted Frank Pick (1879-1941), managing director of London Underground. All eight prints are seen together and encourage use of the London Transport network for reaching leisure and sporting activities. Changes in society and working (and workless) patterns after the Great War gave sections of the population free time, and sometimes money., to expand their horizons.

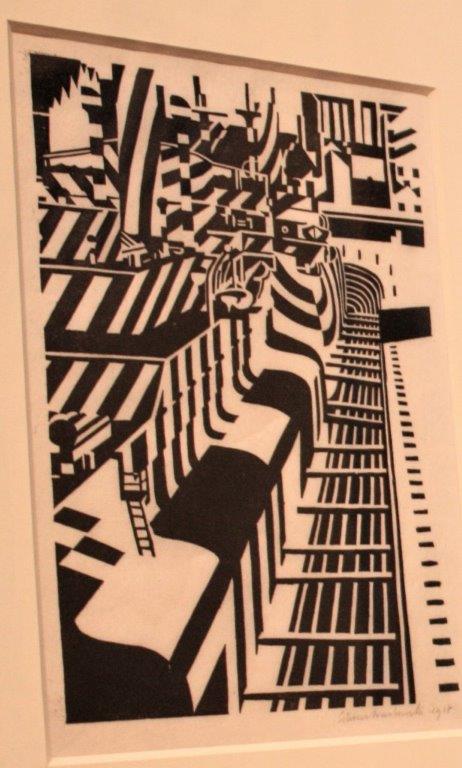

Cyril Power and his fellow artists were drawn to the originality of Tube infrastructure and even its passageways. Power’s Whence and Whither is a study of commuters descending the escalators at Tottenham Court Road on the Northern Line. The robotic, identikit passengers are on their daily dive into the dim subterranean world.

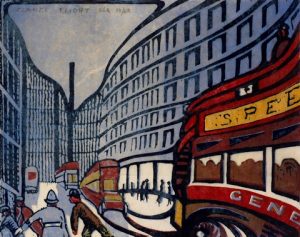

The artists especially loved London’s red double-decker buses, which are the “heroes” of several studies. Claude Flight’s Speed is one of several celebrations of buses plying streets lined with faceless buildings. Scenes of this type pack in so much movement that they appear to create an expanded field of vision. Cyril Power takes us for a bumpy bus ride in The Sunshine Roof.

Sports illustration was in a fledgling state, and benefits from the imagination of the Grosvenor group. One of the Andrew Power posters shows the agile players of Wimbledon seemingly leaping from a two-dimensional court to aim their shots beyond the picture frame.

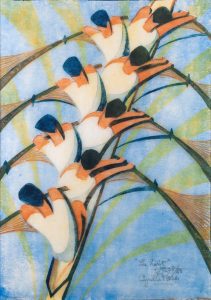

Many of the racing and entertainment depictions seem to jump off the wall. Power’s Speed Trial is a motor race that has the force and coloration of a roaring sea. A similar verve animates his madcap Merry-Go-Round, and his tribute to team rowing The Eight.

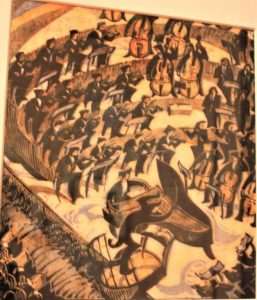

Enthusiasm for music is echoed on a grand scale in Concert Hall, from 1929 by Sybil Andrews. In Power’s 1935 linocut The Concerto, orchestral players and their conductor are almost transformed into musical notation. Power, a talented violinist and pianist, and Andrews had squeezed a piano into their shared working studio.

Among international loans receiving their first major UK showing are prints by the Australian students Dorrit Black, Ethel Spowers and Eveline Syme. Spowers might have been less than impressed by the London weather, if the geometric arrangement of umbrellas in Wet Afternoon is anything to go by.

Claude Flight’s genius was to recognise the ability to create memorable works from linoleum, which had been invented in the 1860s as a cheap floor covering, by coating cork and linseed oil on a canvas backing. He wanted there to be “a linocut in every home, affordable to an ordinary working man or woman,” although the modest prices for such works were beyond the means of many who would have loved one. Flight envisaged linocut lending libraries, and exhibitions in cinemas.

Dulwich’s layout begins by putting in context the influences on Flight and his students. These included the avant-garde movements of Futurism, Vorticism and Cubism, and the impact of World War I. Especially moving is the 1916 depiction in drypoint of Return to the Trenches by Christopher Nevinson. Edward Wadsworth (1889-1949), a member of the Vorticists, was involved in supervising the camouflage of Royal Navy ships with dazzle designs, the subject of many of his woodcuts, including Camouflaged Ships in Drydock, a 1918 engraving on Japan paper. The dazzle pattern was meant to confuse enemy gunners about a ship’s direction and speed. Wadsworth and others went on to use printmaking to create work derived from their wartime experiences, while the Grosvenor School followers focused on representing everyday objects and activities.

Flight and Nevinson had been fellow students and developed in common a way of relaying the pace and dynamism of urban life.

The Grosvenor School artists were inspired by Futurism but translated everyday scenes including manual labour into their compositions. The Swiss artist Lill Tschudi was attracted to themes such as Sticking Up Posters (1933) and Fixing the Wires (1932).

A wall panel quotes the words from 1915 of the Russian Futurist Kazimir Malevich: “There is movement and movement. There are movements of small tension and movements of great tension and there is also a movement which our eyes cannot catch although it can be felt. In art this state is called dynamic movement. This special movement was discovered by the Futurists as a new and hitherto unknown phenomenon in art, a phenomenon which some Futurists were delighted to reflect.”

Of the new show, Gordon Samuel said: “What will strike visitors are the vivid colours and the modernity of the work – amazing to think that these were made over 90 years ago and remain just as compelling today as back in the 1930s!”

Jennifer Scott, the Sackler director of Dulwich Picture Gallery, hailed a “brilliant exhibition within [Dulwich’s] theme of innovators. It captures a movement at a moment when Britain needed art in that interwar period.

“With instantly recognisable and relatable themes, the rhythms of daily life represented in these artworks created nearly 100 years ago still feel immensely poignant today. There has never been a better time to bring together such important reminders of the essential links between life and art.”

In the splendid catalogue for the exhibition, the historian Dr Leaper concludes that this was “one of the most aesthetically cohesive, yet critically undervalued groups in British art.

Captions:

The Tube Station, 1932. By Cyril Power. © The Estate of Cyril Power. All Rights Reserved, 2019/Bridgeman Images.

The Tube Station (proof in Chinese blue, 5 of 6 colour proofs), c.1932, © The Estate of Cyril Power. All Rights Reserved, [2019] / Bridgeman Images/ Photo The Wolfsonian–Florida International University, Miami Beach.

The Tube Train. Linocut, c 1934. By Cyril Power.

Wimbledon. By Andrew Power. 1933, © The Estate of Cyril Power. All Rights Reserved, 2019 / Bridgeman Images/©The Estate of Sybil Andrews © TfL from the London Transport Museum Collection.

Speed. By Claude Flight. 1922, © The Estate of Claude Flight. All Rights Reserved, [2019] / Bridgeman Images/ Photo © Elijah Taylor (Brick City Projects).

Speed Trial. By Claude Flight. c 1932, photo Osborne Samuel Gallery London/ © The Estate of Cyril Power. All Rights Reserved, [2019] /Bridgeman Images.

The Merry-Go-Round. By Cyril Power. C 1930, © The Estate of Cyril Power. All Rights Reserved, [2019] / Bridgeman Images/ photo the Wolfsonian–Florida International University.

The Eight. By Cyril Power. © The Estate of Cyril Power. All Rights Reserved, [2019] / Bridgeman Images/ Photo © Elijah Taylor (Brick City Projects).

The Sunshine Roof. By Cyril Power. C 1934. © The Estate of Cyril Power. All Rights Reserved,

[2019] / Bridgeman Images/ photo Osborne Samuel Gallery.

Wet Afternoon. By Ethel Spowers. 1929-30., Photo Osborne Samuel / ©The Estate of Ethel Spowers.

Concert Hall. By Sybil Andrews. 1929, © The Estate of Sybil Andrews/ photo Osborne Samuel Gallery.

Cyril Power. The Concerto. Linocut. 1935.

Camouflaged Ships in Drydock, 1918. Wood engraving. 1935. By Edward Wadsworth.

Cutting Edge: Modernist British Printmaking is at Dulwich Picture Gallery until September 8, 2019. Open 10am – 5pm, Tuesday – Sunday (closed Mondays except Bank holidays).

1 comment

Quality posts is the important to interest the users to visit the website, that’s what this site is providing.