A Century of the Artist’s Studio. Glimpses of the “coalface” at latest Whitechapel Gallery exhibition

By James Brewer

Highly controlled chaos: that was how the painter Francis Bacon, known for his distorted and nightmarish figurations of man and animal on the canvas, viewed his studio. Amid seeming disorganisation, the implication is: “It might look a mess, but I know I can find anything I want.” It is a natural milieu for artists with their sheaves of brushes, panoply of paint pots, and splotched working gear.

Such is the contradiction of any studio, every one of which reveals a great deal about the occupant.

In a packed new exhibition, London’s Whitechapel Gallery gives over its four main galleries and an auditorium to an insightful display of the role of the studio over the last 100 years, through the eyes of artists and image-makers from many disciplines and from many countries and periods. It is an eclectic, to say the least, collection of objects and representations, but a fascinating one – ranging from the greats who are no longer with us, to our contemporaries, the most recent being a Cypriot who has lent her room-high textile curtain which was previously on show in a 2021 exhibition at the library of the Greek parliament.

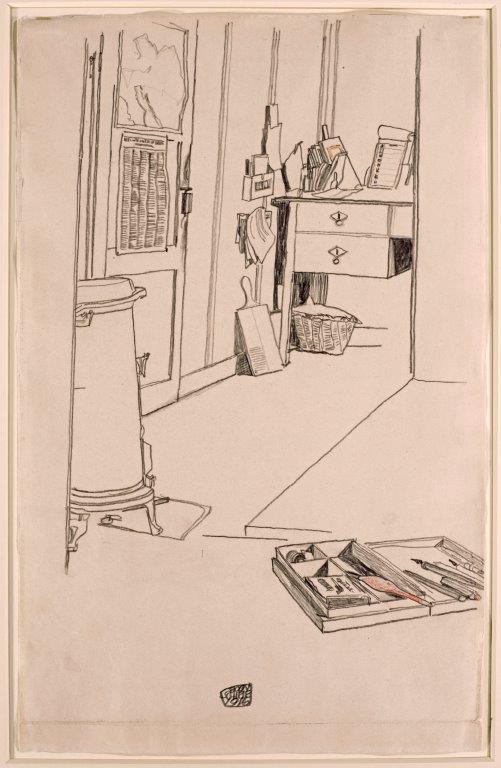

Among unexpected environments, we learn of the constrained circumstances in which one of Egypt’s first female political prisoners for more than four years portrayed her fellow inmates, and of World War I conscript Egon Schiele who set up studio in his commander’s office in a prisoner of war camp.

In all, here are more than 100 works by 80 artists and collectives from Africa, Australasia, South Asia, China, Europe, Japan, the Middle East, North and South America. This seam of the ‘coalface’ where artists work has been expertly quarried by outgoing Whitechapel director Iwona Blazwick as lead curator of her team.

They give glimpses of the processes of practitioners ranging from much talked-about icons such as Bacon, Louise Bourgeois, Pablo Picasso, Frida Kahlo, Egon Schiele, and Andy Warhol, to contemporary figures such as Walead Beshty, Lisa Brice and Kerry James Marshall.

Of the studios featured, there are few pristine examples. The impression lingers of the messiness of many of the masters.

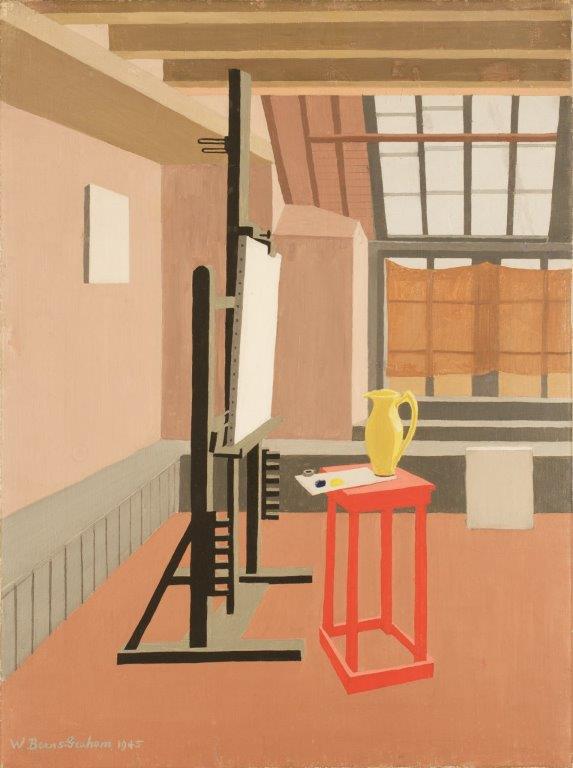

Someone who did seek to put things in order, in her oil painting Studio Interior, was one of the foremost painters working in St Ives after 1940, Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (1912-2004). In this 1945 work, she imagined a pristine studio, although the reality for her and everyone else was different. Her workspace was well used, and that is the point – she retained her studio in the Cornish town renowned for its quality of light and attractive landscapes until her death. Studio Interior presents the opposite of Bacon’s controlled chaos in his small first-floor Chelsea atelier which measured only 4 by 6 metres.

The charismatic, generous, champagne-quaffing Bacon worked for more than 30 years at 7 Reece Mews amid a jumble of photographs, books, catalogue pages, newspaper cuttings, discarded canvases, painting materials, and other clutter.

The harshness of Bacon’s portrayals is a turn-off for many people, but he is recognising what he calls “the brutality of fact,” a phrase scrawled on a memo pad on the wall of his studio. The art critic David Sylvester used The Brutality of Fact as the title of his 1987 book of interviews he had conducted with Bacon during a period of 25 years.

After Bacon’s death in 1992, his companion for long years and heir, John Edwards, determined to preserve what he could, and arranged for art historians, conservators, and archaeologists to dismantle the room for shipping and resurrecting at the Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery of Modern Art, Dublin, the city where Bacon was born in 1909. With 7,000 items including old corduroy trousers which he used to cut up to add texture to his paint, the reconstruction in a purpose-built compound was opened to the public in May 2001.

Another London luminary and merciless chronicler of the uglier aspects of the human body, Lucian Freud (1922-2011), allowed very few people in his studio. His home and studio from the late 1970s to the 1990s was a fourth-floor walk-up in a Victorian townhouse – some people dubbed him the hermit of Holland Park.

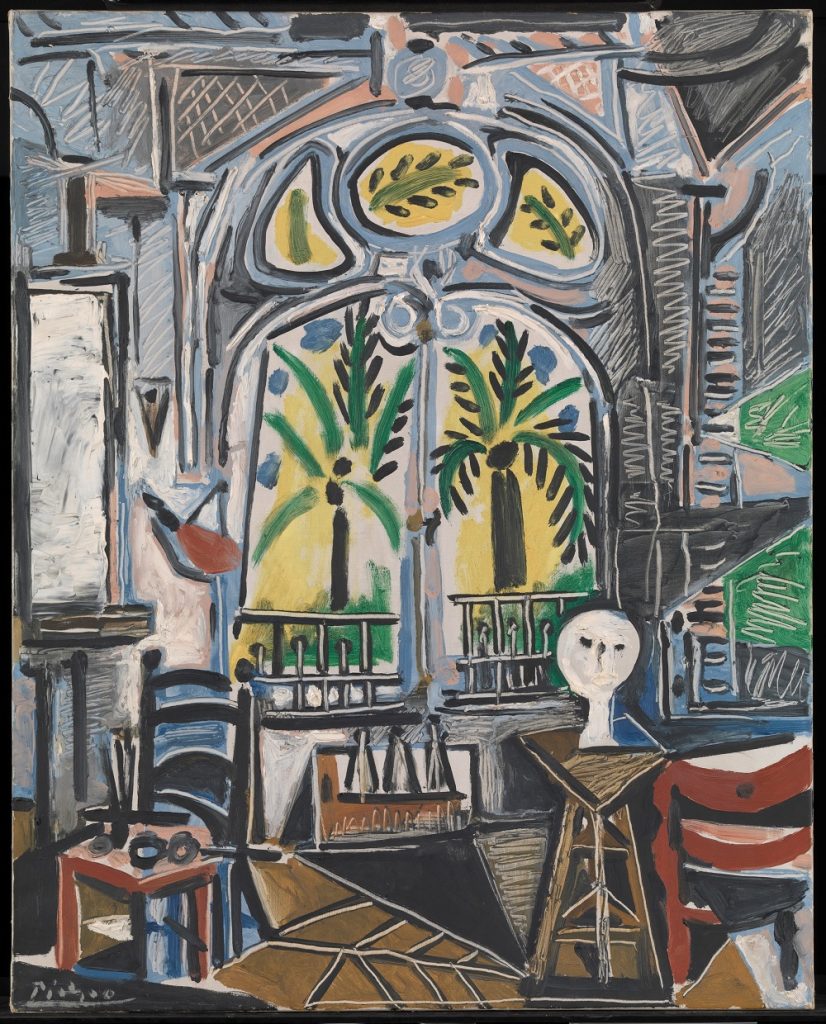

Picasso with his partner Jacqueline Roque was able to work from a much more comfortable base, to which they had moved in the summer of 1955. He used the large main salon on the ground floor of the 19th century Art Nouveau villa La Californie near Cannes as his workplace and to receive friends and dealers.

Among memorabilia from Henri Matisse’s finely furnished lair in Nice can be seen a 1950 sepia illustration of a woman of Martinique to Poésies Antillaises by John-Antoine Nau This picture is from the ISelf Collection which was established in 2009 by Maria and Malek Sukkar and curated and managed by Anderson O’Day Fine Art. Matisse (1869-1954) shared with Nau a love of the West Indian island and he made 27 drawings to illustrate the book, published only in 1972.

One of the starkest settings for a studio was in a wartime prison camp. Egon Schiele. the controversial pioneer of Austrian expressionism (one might almost say, a forefather of Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud) brought his watercolours and drawing materials with him when he was conscripted, three days after his wedding in 1916. Schiele began sketching Russian prisoners, whom he was ordered to guard. His commanding officer gave him a disused storeroom to use as a studio, which he depicted on paper in pencil and black and red crayon. He and his wife Edith died from the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918 – he was 28 years old, and she was pregnant.

Occupying a corner of one room at the Whitechapel is a partial reconstruction of the studio of Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948), who variously favoured dadaism, constructivism, surrealism, and sculpture. Originally from his house Merzbau (he called his collages Merz Pictures) in Hanover from 1923-33, it was a “spatial collage that was both studio and art” and has been an inspiration for many installation artists. Schwitters started his Merzbau over again whenever he moved home, and a travelling version has been mounted and dismounted many times. The original Merzbau was destroyed by a British air raid in October 1943.

Another home as studio replicated here is the cottage of the Canadian folk artist Maud Lewis (1903-1970) who, suffering from arthritis from childhood, covered all the surfaces of her Nova Scotia home with bright and joyous paintings of flowers, birds, butterflies and cats.

Displayed after being exhibited in the newest arts attraction of Athens is a curtain-like site-specific installation in cotton, linen, silk threads and metal by Cypriot-born Maria Loizidou. Called A Monumental Lightness, it was commissioned by NEON, a non-profit organisation founded in 2013 by the collector and entrepreneur Dimitris Daskalopoulos, for the exhibition Portals, which was at the library of the Hellenic Parliament, in the Colonus district of the capital, in the second half of 2021.

The 19,000 sq m library building is the former Public Tobacco Factory, constructed in 1930, which ceased production in 1995. In 2000, the building was transferred to the Hellenic Parliament, as storage for its library and publications department, and a €1.2m renovation funded by Mr Daskalopoulos was carried out. The Portals exhibition commemorated the 200th anniversary of the Greek War of Independence and featured 59 artists from 27 countries.

Maria Loizidou, from Nicosia, works extensively with fabrics and has said that “a work of art can only be considered such if it offers a new message to the world.”

Her artwork is placed adjacent in the Whitechapel show to the ostentatious chimneypiece decoration that Duncan Grant (1885-1976) carried out at Charleston, the country home in Sussex of Grant and Vanessa Bell. In 1916 the artists enthusiastically went to work to transform the place, a residence beloved of members of the Bloomsbury Group.

In striking cobalt blue hues, Lisa Brice (born 1968) depicts assertive women as she considers the female figure as both artist and studio model. She seeks to dispense with the hierarchy between artist and model inferred in historical studio scenes of male painters and their female muses. Lisa, who is based in London, cites her experiences growing up in South Africa during political upheaval, and time spent living and working in Trinidad where she had a residency, as among her influences.

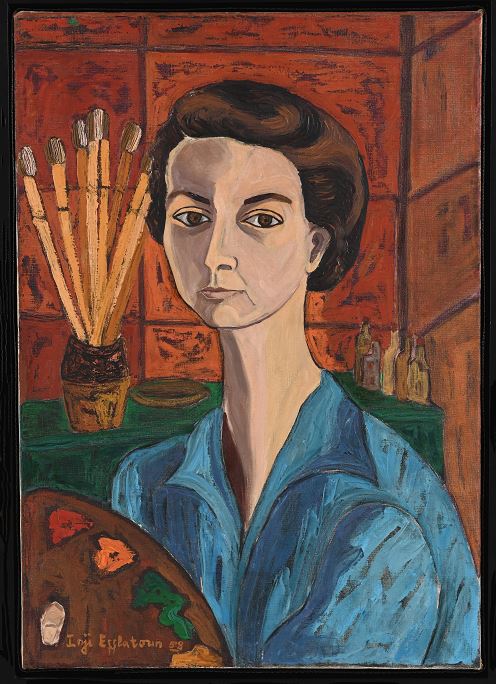

A demure self-portrait of Inji Efflatoun (1924-1989) with its jar of brushes in the background looking almost like a vase of flowers, belies her impressive struggle for human rights. An Egyptian painter and activist in the women’s movement, she was born into the aristocracy but in her paintings pointed to social injustices. Jailed from June 1959 to July 1963 by the Nasser regime for belonging to the Communist Party, she was one of Egypt’s first female political prisoners. She sought every opportunity while behind bars to practise her art and show the world the grim reality of women’s prisons, even though she was banned from time to time from doing so. She smuggled each canvas to the outside world by giving it to a warden to wrap around her body under her clothes. “Prison was a very enriching experience for my development as a human being and artist,” declared Inji Efflatoun.

Praise is being bestowed on Iwona Blazwick who is leaving Whitechapel Gallery in April 2022 after 20 remarkable years of leadership. She will continue to work as an independent curator with the institution into 2023, and on other international projects. She expanded the gallery’s exhibition, education, commissioning, and publishing programmes, and in 2009, doubled the size of the site by transforming the adjoining former Whitechapel Library into new galleries and studios. She notably strengthened Whitechapel Gallery’s commitment to showing pioneering women artists.

Captions in full:

Untitled. By Lisa Brice. 2019 Oil on trace. © Lisa Brice. Courtesy the artist; Stephen Friedman Gallery, London; Salon 94, New York; and Goodman Gallery, South Africa. Katrin Bellinger Collection.

Portrait of Inji Efflatoun. By Inji Efflatoun. 1958. Oil on canvas. Courtesy Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art.

Studio Interior (Red Stool, Studio). By Wilhelmina Barns-Graham. 1945. Oil on canvas. © Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust.

Office at the Mühling Prisoner of War Camp. By Egon Schiele. 1916. Black and red crayon on ivory wove paper. Katrin Bellinger Collection.

Illustration to Poésies Antillaises, 1950, from the book by John-Antoine Nau, printed in sepia, ink on paper. By Henri Matisse (1869-1954). ISelf Collection.

A Monumental Lightness by Maria Loizidou (1958 Cyprus). 2021/2022, Site-specific installation cotton, linen, silk threads and metal. Commissioned by NEON for the exhibition Portals, Library of the Hellenic Parliament, former Public Tobacco Factory, Athens.

Chimneypiece by Duncan Grant (1885-1976). Oil on board. Courtesy the Charleston Trust.

L’Atelier (The Studio). By Pablo Picasso. 1955. Oil on canvas. © Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2021

A Century of the Artist’s Studio is at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, until June 5, 2022.