Lady Liberty on the cover.

American P&I Club launches masterly centennial history of its role in global insurance

By James Brewer

Poetry and P&I is an unlikely partnership, but it was there at the foundation of the American Club. A propitious collaboration of a ruthless broker and a frustrated poet in 1917 created a protection and indemnity insurer that went on to weather immense turbulence, emerging after 100 years as a solid and expanding institution.

The New York-based mutual is now navigating confidently its specialist market, having steered into the mainstream after clinging to a patriotic but basically unviable “American only” ethos for its first 63 years.

A symbol of this triumphant survival is a book commissioned by the club and entitled The American Club: A Centennial History (published by CorporateHistory.net), fit to grace any coffee table, boardroom, captain’s table or shipboard library.

United States Lines offered passenger and cargo services

The volume is a paean to P&I and its manifestations and can serve as a primer for anyone who wants to know about the genesis of this branch of insurance, and how it functions. More broadly, the book articulately puts the evolution of the club in the context of ten dizzying decades of maritime, marine insurance and social history as it has affected the US and the whole world.

The author Richard Blodgett, a former Wall Street Journal reporter who has chronicled the stories of the New York Stock Exchange, manufacturer Kohler & Co and JP Morgan Chase, relates the ups and downs of the club sympathetically, without sparing details of earlier misguided policies – policies in both senses of the word. In one of its early years, the club was briefly the largest P&I club on planet ocean, only to dwindle to one of the smallest.

Blodgett declares from the outset in Chapter One that P&I clubs are among the most unusual insurance companies in the world, citing authorities including Lloyd’s List, the Journal of Commerce and the Nautical Institute. Putting aside the mystique, the basics are that the clubs are groups of shipowners or related interests who insure each other against liability risks.

P&I clubs, it is claimed, invented liability insurance. They took off in the UK after a judge ruled in 1836 that a shipowner’s hull policy did not cover collision damage inflicted on another ship.

The first P&I club, in 1855, was Shipowners’ Mutual Protection Society, the forerunner of today’s Britannia. By 1900 there were nearly 20 P&I clubs in ports in the UK, Norway and Sweden.

Shipowners in the US bought their liability cover from clubs in the UK before the outbreak of World War I. Once the war began, American shipping pulled out of its recession to revel in a global shortage of vessels and booming freight rates. Shipyards were called on to build hundreds of new vessels.

Strangely, it was British jingoism that led to the formation of an American P&I association. While Washington kept out of the war, ships continued trading with Germany. This went down badly in London, which sought to punish 82 American corporations, mostly New York-based companies with German-sounding names, for “trading with the enemy.” Among other sanctions, UK-controlled seaports denied access to cargo from the corporations.

The Royal Navy was ‘illegally’ boarding and searching American ships bound for Germany. and US steamship lines were barred from buying cover from British P&I clubs. They were caught between a rock and a hard place: the US Justice Department warned the shipowners that they would violate US antitrust law if they refused to carry freight for the 82 firms.

Robert Dollar (Library of Congress).

The simplest way out was for the US owners to form a P&I insurer based in the homeland to provide a reliable source of coverage. This was vigorously driven through by WH LaBoyteaux, president of Johnson & Higgins, the leading US marine insurance broker at that time.

LaBoyteaux – a stern and intimidating boss and a keen racehorse breeder – worked on the project with Russell Loines, a poet who had been unable to make a living out of his literary talents and joined Johnson & Higgins, where his father was a senior partner.

At the broker, Loines became manager of a department for placing business on behalf of clients with P&I clubs in the UK. As early as 1904, he toyed with the notion of creating an American P&I club. He lived to see this dream come true, but sadly the popular broker died in 1922 at the age of only 48.

LaBoyteaux had entered Johnson & Higgins at the age of 22 as an average adjuster and in 1916 rose to the rank of president, where he exercised absolute authority – and collected one of the highest salaries in the nation – for 31 years until his death.

LaBoyteaux and Loines modelled their enterprise on the structure of London P&I Club, where Loines had worked for a short time. The formal name of the new club, American Steamship Owners Mutual Protection and Indemnity Association, was based on that of London Steam-ship Owners’ Mutual Insurance Association.

Using their influence and contacts, the two men managed to get the necessary legislation approved unopposed by New York State, just over a month before February 20 2017, that date being the annual renewal day globally for P&I cover. The new law paved the way for incorporation and charter papers to be granted on St Valentine’s Day, and the club began recruiting members – Johnson & Higgins had been canvassing since early that year. It was all the easier because the war had eroded the loyalty of American shipowners to clubs based in Britain.

Who was the first member of the American Club? You might be hard put to guess correctly. It was Cuba Distilling Co, a New York-based company which produced 80% of the molasses in Cuba. It was owned by the United States Industrial Alcohol Co, which in turn was a subsidiary of Standard Oil of New Jersey. The company enrolled in the club the five tankers which it used to transport molasses for conversion into industrial alcohol in New Jersey.

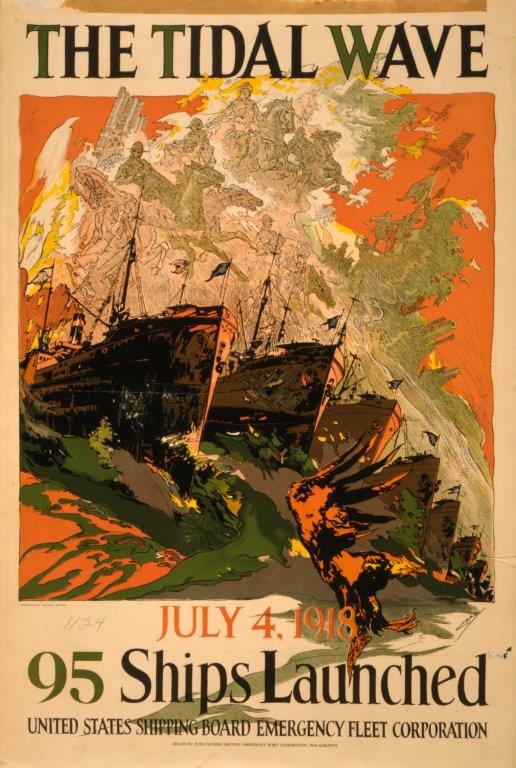

Patriotic poster, 1918. (Library of Congress).

Following this were enlisted eight passengerships of Old Dominion Steamship Co, the dominant line between New York and Virginia, in an era ahead of airliners and interstate highways.

The minimum book for the club’s insurances to become effective was 200 vessels of 500,000 tons – and this was exceeded on the first day, but it took five days for a document to reach New York from California, so the directors changed the rules to accept applications by telegram. By the end of August, the club had 50 members who controlled nearly 1.2m tons. Included were some of the biggest names in the sector, including American Hawaiian Steamship which was benefiting from the opening of the Panama Canal and deploying oil-fired tonnage, and banana importer United Fruit and its London subsidiary Elders & Fyffes.

The first claim paid by the American Club in 1917 was $20, to a seaman who was injured in an accident on an oil tanker. Today’s clubs are strong enough collectively, thanks to powerful reinsurance backing, to pay claims as large as the record $1.5bn occasioned by the Costa Concordia disaster in 2012.

Unsurprisingly, Johnson & Higgins was appointed club manager, having brought in the early business. Half of each risk was reinsured with the London Club, which reinsured American tonnage for other competitors, more than making up for the loss of many of its US members. The friendly relationship would be rewarded many years later when the London Club manager A Bilbrough & Co supported the American Club’s application to join the International Group of P&I Clubs.

Despite a brisk start, the American Club faced a potential deathblow a couple of months later. When the US entered the war in April 1917 the need for a large merchant fleet posed the question of whether to nationalise the maritime industry, or to provide huge subsidies to the lines. It chose the former option. The federal Shipping Board requisitioned ships, chartering them back to the original owners, took over the nation’s shipyards and ramped up production. Industrialists such as Robert Dollar, president of Dollar Steamship Co, railed against this government “interference.”

Old Dominion Line – an early club member.

Ships were withdrawn from the club, and the government took on self-insurance. The scheming LaBoyteaux came up with a rescue plan for the club: he allied himself with the Shipping Board, became chairman of its advisory insurance committee and convinced the board to enter its ships in the club. Loines finalised terms with the board for its purchase of cover, which not only saved the club, but gave it an enormous boost in tonnage. P&I was the only function outsourced by the board..

The deal lasted well after the war, making the board the club’s largest member by far, at 9.4m tons. Indeed in 1922 the American Club was probably the largest in the world. Its miscellany included 74 old-fashioned French full-rigged sailing ships under condition they stuck to “safe waters.” Another quirky entry was a batch of 323 wooden, steam-powered freighters built for Emergency Fleet Corp “as part of our plan to crush the German Kaiser,” as a magazine put it.

The fruitful relationship between the club and the board snapped when the latter failed to pay its premiums in time, blaming procrastination by Congress. Tonnage slumped to 1.7m, although the club was financially sound and included “the cream” of the American-flag industry: 90% of the country’s privately-owned ships.

The problem for owners was that with high operating costs, ships were being forced into lay-up. Overtonnaging – a familiar story periodically ever since – hit freight rates and profits, so that in 1921 half the world’s oceangoing tonnage was idled, and some club members went bankrupt. Those which thrived were Alaska Steamship thanks to the protectionist Jones Act, and operators that played the secondhand market skilfully.

In 1927, amid signs of a market upturn, the club moved out of the offices of Johnson & Higgins, which formed a new subsidiary named Shipowners Claims Bureau, as club management. The same year it won as a member Standard Oil of New Jersey with its 450,000 tons of tankers, barges and workboats. That company remained a member until 1942.

The Great Depression was not the only enemy of shipping. Prohibition which lasted from 1920 to 1933 was a drag on the American industry. What with illicit drinking and bootlegging by seafarers and others, Prohibition was a nightmare for the steamship industry and there was enormous relief upon its repeal, says Blodgett.

After a brewery chief found that German beer was being sold on an American ship, the attorney general proclaimed that all domestic ships had to be “dry” wherever they sailed. United American Lines switched to the Panama flag and other lines sought to do the same, until the Supreme Court changed the official line.

By 1938 American-flag tonnage accounted for only 13% of the global total, which was bad news for a club insuring domestic tonnage only, and again world war saved it from collapse. In an unprecedented shipbuilding spree, the US Maritime Commission backed construction for the War Shipping Administration of nearly 6,000 cargoships and tankers between 1941 and 1945.

This time many of the shipyard workers were female, replacements for men who had gone off to war. A photo courtesy of the US National Park Service shows smiling women at a shipyard posing with signs listing their jobs – machinist, pipefitter, tank cleaner, welder, sheet metal worker, rigger, welder and so on. By 1943, nearly two thirds of the shipyard workers on the US west coast were women.

Women were linchpin of American shipyards.

Through an agency, the government divided P&I coverage equally among four insurers including the club, but nearly all of it was on fixed-premium rather than mutual basis, and there was little profit in it. The four underwriters insured 5,400 vessels and paid nearly 350,000 losses.

After the war was over, club member United States Lines and its competitors bought scores of ships surplus to military requirement, and many of them came off the club’s books. At the same time, British and Scandinavian clubs became more active. The American Club had to rely on its loyal, long-term members, and the years to 1971 were difficult for the club, which admits it almost went out of business. One of the compensatory successes was providing cover for the large transatlantic liner SS United States, launched in 1952.

From 1950, the worldwide merchant fleet grew steadily, but the main growth was outside the US, with Greece and Panama playing facilitating roles.

Havana port as used by Cuba Distilling Co.

As early as 1949, the managers recommended the club begin insuring foreign-flagged ships, but the question was shelved for 22 years. Membership dwindled to nine companies, and claims costs were rising, although the big broker Marsh & McLennan began placing business. But the club struggled to maintain its reinsurance cover, after an American backer upped its prices. Leading Lloyd’s underwriters Peter Cameron-Webb and then Peter Green gave the reinsurance a shot. United States Lines switched to the UK Club. At renewal in 1971, half the members left after Marsh assessed the business had too little spread of risk and was too pricy. Even Johnson & Higgins deserted. Tonnage slumped to 1.4m tons (at that time the UK Club had 44m tons). Charles and Adolph Kurz (“a 100% American Club man”) of Keystone Shipping provided a bedrock of loyalty; but when the managers met George Handley, head of Marsh’s marine department, and other brokers, the club was urged to admit foreign-flag tonnage.

Jack Cassedy, a Johnson & Higgins man today in his eighties, became without any P&I experience president of Shipowners Claims Bureau in 1972 and heroically led innovation. The club expanded its recruitment in the tug and barge sector, which remains one of its strengths. On the disbandment of the Great Lakes Pool, the club moved into that sector. To assist the cash flow of owners, the clubs allowed premiums and supplementary calls to be paid in instalments.

These efforts, together with a marketing drive, brought newfound confidence and the club even won some tonnage from UK-based clubs. In December 1973, the club “bowed to reality,” as the book puts it, and voted to admit foreign-flag tonnage, although the first “foreign” member, Netumar of Brazil, was signed only in 1980. The first Greek-flag member was Trade & Transport Inc in 1985, opening the way for other Greek members and more recently for the establishment of a Piraeus office to serve their needs more fully.

Opening the doors wider was the beginning of a complete overhaul. As of 2016, nearly 90% of club tonnage was controlled by members domiciled outside North America.

American Club directors today.

Efforts to achieve full internationalisation in the 1970s had stuck on the thorny question of reinsurance. Talks were held with West of England P&I to take on the reinsurance role, but this hit came to nothing. For 17 years, the club had to buy reinsurance independently, via Green and Cameron-Webb, until at last it gained access to the International Group pool. It was also thwarted in its attempts to provide liability cover for oil spills, when it found reinsurance terms quoted by London, New York and Bermuda too expensive. This was a hurdle which American owners needed to see resolved, following the Torrey Canyon disaster of 1967, which prompted fears of even bigger spills as crude carriers were built on an ever-larger scale.

Another blow was the filing of claims by seafarers who had worked on American ships insulated by asbestos, a material that had been mandated because of its fire-resistant properties. By 1987 the club had paid 127 disease claims related to the carcinogen, and was processing 1,400 more.

It was an insidious threat both to health and finances, because asbestos-related illness could manifest itself 20 or more years after exposure. Perhaps the biggest shock of club’s history was to be slammed in 1993 by an order to indemnify bankrupt Prudential Lines against asbestos-related claims to the tune of $66m – this was only a partial judgment and it was feared the figure could spiral into hundreds of millions. The judgment was thrown out on appeal, but this was just the beginning of a tortuous process to sort out the claims of dozens of former owner-members. It took until 2008 until a solution could be devised, by means of a cut-off date of 1989 for paying claims of former members.

American Club managers.

As so often before, despite the headaches, the club directors decided that theirs was an institution worth saving, not least because they appreciated the “excellent claims service.”

In 1994 the club called in management consultants who drew up a plan called Vision 2000, which included setting up a London office (headed for many years by now retired Ian Farr), aligning more closely with practices of other P&I clubs including a system of release calls to cover possible future liabilities on open years from members leaving, and the appointment of a new chief executive – enter Joe Hughes, lured from Jardine Insurance Brokers and previously at Gard and Steamship, who is at the helm more than 20 years on.

Hughes vigorously pursued the ambition of membership of the International Group, and after many rejections the club was finally admitted in 1998. It was a life-changing experience for the club. Entered tonnage grew and the membership profile changed, tilting towards the eastern Mediterranean and Asia. “It was now an American club serving the world,” writes Blodgett, adding that American companies too recognised the mutual was no longer a “fringe player.” Vince Solarino came on board as chief operating officer and guided the club into strengthening its balance sheet, especially building a strong ‘free reserve’ safety net.

Shipowners Claims Bureau (Hellas) team.

The Piraeus office opened in 2005, from where its managing director Dorothea Ioannou is global business development director. Shanghai office followed in 2007 and Hong Kong in 2013. Members domiciled outside North America now account for some 85% of insured tonnage.

The club has looked further afield in product, too. It opened Eagle Ocean Marine, a fixed-premium P&I and freight, demurrage and defence provider for smaller ships, with one company for non-US trade operations and another for US operations.

In 2016, it entered the hull and machinery market by investing in a new insurer, American Hellenic Hull, based in Cyprus.

The current club chairman, Arnold Witte of Donjon Marine, said: “This book celebrates the club’s first century with an eye to a bright future.”

Certainly, every page – all 150 of them – crackles with fresh aspects of marine and social history and underlines the often-understated role of mutual and commercial insurance over the past 100 years in supporting global trade and transport.