Richard Duda

Heritage of a reviving Jewish community comes into view in Košice, Slovakia, By James Brewer

Lay and religious devotees are unlocking the story of one of the most important Jewish communities of the past century and a half in Europe, creating renewed interest in Judaism and expressions of its culture.

Tourists and historians who visit regions such as east Slovakia are able to follow heritage trails that bring out both the fearful tragedy of a persecuted people and elucidate poignantly the tenacity of the survivors.

Even non-Jews, for example living in and around Košice, the elegant second-largest city of Slovakia, are unaware of how deep was the impact of Jewish residents on the commerce and culture of their region before the Holocaust did its horrendous work.

Dome of former synagogue, Košice.

To their credit, tourist officials in Košice and in other areas are actively fostering the spread of knowledge of the patrimony.

Albeit with few public signposts, and without dedicated visitors’ centres or car parks, specialised one and two-day tours focusing on Jewish heritage are being promoted in the East European nation.

Learning in detail how the Nazi cataclysm devastated once thriving populations, and seeing the sometimes ruined bricks and mortar of bygone epochs of Judaic life is a moving experience and repays the effort of tracking down the sites.

Orthodox synagogue, Košice.

Before the Shoah, Košice hosted one of the biggest and most prominent Jewish congregations in the territory that comprises present-day Slovakia. All this rich communal life was destroyed principally between May 16 and June 5, 1944, when almost all Jewish citizens of Košice were deported to Auschwitz.

The community never recovered numerically. Today, it has only between 280 and 300 members. Still, it is the second largest Jewish community in Slovakia, and it strives to pursue an active life.

Around 30, 000 Jews found themselves within the boundaries of present-day Slovakia following the end of World War Two, and sought to reconstruct their social life and businesses, but thousands left after the establishment of the Communist regime in 1948 for Israel, the US, Canada, Australia and other countries. An official silence fell over what had happened during the darkest days. Since the post-Communist dawn many of the 3, 000 Jews living in Slovakia have worked to recover and preserve their heritage.

Memorial plaque on Orthodox synagogue, Košice.

Jewish customs and traditions can be traced in buildings, not always easy to identify, scattered in the central streets of Košice, and are now celebrated more patently in the annual festival of culture Mazal Tov that has made a great contribution to the city since 2012 and brought deserved praise for its organisers and participants.

Reflecting its importance across the Hebrew kaleidoscope, Košice had flourishing congregations following the Hassidic, Orthodox, Neological, and Status Quo Ante branches. The improving social and economic status of the Jewish population during the 19th century to a great extent stemmed from a charter of religious toleration enacted by the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II in 1789.

Austria-Hungary granted the Jews equal rights In 1867, when the city population numbered about 300 families. Most of them made their living through trade, craftsmanship, free professionals, or entrepreneurs who set up factories, mostly to process agricultural products.

Richard Duda, current secretary of the Jewish community in Košice, speaks of the terrible days when between 12, 000 and 15, 000 people were deported from the city to death camps. Where once there were five synagogues, there are two, only one of which is fully functioning.

Menorah with symbols of the Holocaust, Orthodox synagogue, Košice.

There has been a long-running legal dispute in which the Jewish community is seeking to recover property confiscated in 1956. A law was introduced in 1993 following the split of Czechoslovakia into Slovak and Czech Republics, allowing Jewish and other religious groups to claim restitution. “We are optimistic there will be a resolution this year, ” says Mr Duda. It has been a bitter wrangle, with documents going back many decades having to be unearthed, and undertones of anti-Semitism emerging from some quarters.

Mr Duda says that the community is trying to become more open and take part in more cultural events. Among other things, the community has its own klezmer music group.

“We want to provide more information for the majority. We are only 300 people – that is a major concern. The majority [of the community] are over 80 years old. It is not an easy job to provide relevant information on our community.” Košice in 2013 was one of the two European Capitals of Culture, and the community used that as a platform.

Resources are a huge problem though. “The total in Slovakia is only 3, 000 Jews, but we have 900 cemeteries and sites to look after, ” says Mr Duda.

Jews numbered 17, 000 among Košice’s 60, 000 inhabitants in 1939, and they were hit by one of the toughest anti-Semitic codes of boycotts, forced divestment and other sanctions. In the summer of 1940 hundreds of the Jews of Kosice were enlisted into forced labour units, and sent to work camps. Four years later, 40 leaders of the community were taken by the occupying Nazis as hostages, for whom a huge ransom was demanded. The ransom was paid, in vain. Soon afterwards, it took just under a month for almost every single Jew to be transported to their deaths; and it took more than 40 years for the community to recover.

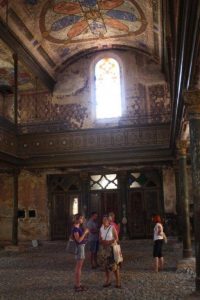

Inside the Orthodox synagogue, Košice.

Opening the synagogue in 2013 was a big step forward and there had been a lot of co-operation from the mayor of Košice. “He is very supportive – a driver [of making things happen]!” enthused Mr Duda.

The mayor is Richard Raši, a Slovak physician who was the country’s Minister of Health for two years until mid-2010. Mr Duda, a businessman whose company sells leather products for the interiors of premium brand cars, is keen that his community continues its excellent relationship with Mr Raši and like-minded people.

A guided tour that can be booked via www.visitkosice.eu begins in front of the House of Art, which was the site of the first synagogue in Košice, razed at the beginning of the 1960s. Between 1926 and 1927 a Neological synagogue was erected next to it with capacity for 1, 100 people and distinguished by a huge dome, reminiscent of the Roman Pantheon and with herringbone decoration. The dome was once topped by a six-pointed star of David, which is now to be found on the Holocaust memorial in the Jewish cemetery. The star was replaced by a gold-painted lute. The synagogue ceased to serve its original purpose after World War II and in the 1950s was used as a grain warehouse, before being rebuilt into the House of Art.

Windows of Orthodox synagogue, Košice.

Nearby is a former educational centre, with an impressive façade, that was linked to the synagogue on the first floor; and a few minutes‘ walk further on is an art nouveau house that was once the Jewish casino – not a gambling hall, but a social meeting place which had a different function from 1962 until the beginning of the 1990s, as a puppet theatre.

The tour culminates at the reconstructed (with oriental and cubist influence) orthodox synagogue on Puškinova street. The premises dating from the end of the 1930s are the work of Košice architect Ľudovít Oelschläger and the builder Hugo Kaboš. Inside, the walls are movingly inscribed in pencil with the words of Jews who were gathered there awaiting transfer to the concentration camps. The Menorah, the candelabra that spreads light, wisdom, and divine inspiration, has symbols of the Shoah, including the rail line that led to the death camp.

Interior of central Synagogue in need of repair, Košice.

It is the only city synagogue to have served its religious purpose perpetually. In the basement of the adjacent Jewish school there was a popular matzo bakery, and the building was a place of hiding for refugees escaping via Košice during World War II from Poland and other countries to Palestine. Local people would feed them and arrange forged papers for them.

The tour sometimes includes the old Košice Jewish cemetery used from 1844 to 1889, and the new cemetery established in 1890.

Košice’s main Orthodox Jewish compound developed near the city centre on Zvonárska [Bellmakers] Street, after the city fortifications there were demolished in the mid-19th century. The Orthodox synagogue built in the 1880s in Moorish style stands empty and in sore need of the restoration that is beginning after decades of use as library storage.

Women’s gallery in central Synagogue, Košice.

Designed by János Balog, a local contractor, its Rundbogenstil western façade, topped by the tablets of the Ten Commandments, fronts onto Zvonárska Street. The currently dusty interior has evidence of its former glory, with richly decorative wall-paintings in geometric and Moorish patterns, and the ark and a basin on the western wall near the main entrance. The compound includes a mikvah (ritual bath) dating from the mid-19th century, the offices of the community and rabbinate, a kosher kitchen , and a prayer room enabling regular services to continue.

It is a symbol of hope for the Jews of Košice.

1 comment

Well done, James! You said it all. What a moving story and what a privilege to be part of this group. We certainly learned a lot about Kosice Jewish culture.