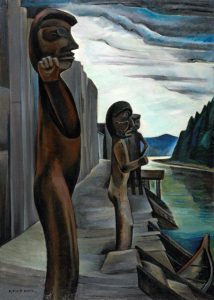

Indian War Canoe (Alert Bay), 1912. Oil on cardboard. By Emily Carr. Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Purchase, gift of A Sydney Dawes.

From the Forest to the Sea: Emily Carr in British Columbia. Dulwich Picture Gallery’s new exhibition celebrates a remarkable artist, By James Brewer

In everything, Emily Carr kicked against the traces. She spent years travelling on her own through the forests of northwest Canada, turning out paintings of “inexplicably beautiful” trees, and sailed up and down the coast in steamers, fishing boats and hired canoes to capture the image of summer seas and skies.

Her glorious spirit of independence and her love of indigenous culture pulse throughout the new exhibition at the Dulwich Picture Gallery, From the Forest to the Sea: Emily Carr in British Columbia.

Her success as an artist and author challenged the status quo to the extent that Georgia O’Keeffe – another great independent artist born in the late 19th century – called her a “darling of the women’s movement, ” although she was not politically active in the conventional sense.

Emily Carr in San Francisco.

Dulwich has assembled a stunning collection of the work of Emily Carr, in clear and passionate context of the lands she worshipped. This rounded show will stop in their tracks even Canadians who have taken their national artist to their hearts.

It is the first major solo exhibition in Europe dedicated to Emily Carr (1871–1945), the youngest of five daughters of a well-to-do merchant and his wife. She grew up in a fine mansion in Government Street, Victoria, the seaport city on Vancouver Island and capital of British Columbia. After the early deaths of her mother and father, Emily set off to train in fine art in San Francisco, and then London (which she apparently hated) and Paris. Her later travels among what are today known as the First Nations established her distinct contribution to the artistic world.

Ian Dejardin, Sackler director and joint curator of the show, said Emily Carr’s determined progress as an artist “makes for an inspiring story of driven creativity, against the odds.

“Her passionate engagement with both northwest coast indigenous culture and European modernism produced a body of work that is unique, rooted in the forests and landscapes of British Columbia. Powerful and evocative, her late images of shimmering sea, living forest and ecstatic skies are a pinnacle of Canadian landscape painting. Her story is one of extraordinary determination.”

Emily Carr, Happiness, 1939. Oil on paper. By Emily Carr. University of Victoria Art Collection, gift of Nikolai and Myfanwy Pavelic.

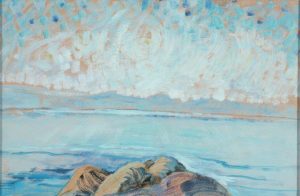

She marvelled at the beauties of nature and railed against ruthless industrial logging. In a book she kept of poetry by Walt Whitman, she highlighted the poem Perfect Miracles, which includes the lines To me the sea is a continual miracle, The fishes that swim – the rocks – the motion of the waves…

In fact the oceans, as the curators say, have always been the source of life and sustenance for the indigenous peoples of the province. Emily Carr’s paintings of seas and skies “surge with cosmic energy and joy.”

Her seascapes are most prominent at the close of her painting career – she turned to writing books after a heart attack – and on show at Dulwich is one of her untitled works on the subject.

Her seascapes are most prominent at the close of her painting career – she turned to writing books after a heart attack – and on show at Dulwich is one of her untitled works on the subject.

In 1934 she had what she calls her “moment of happiness” – she bought a caravan and draped it with various tarpaulins. Between 1934 and 1937 this contraption transported her and her dogs and other pets thousands of kilometres. She bought cheap paper by the quire and thinned her oil paint with … petrol. Plunging into landscape painting, she conveyed with her bold brushstrokes the majesty of the trees around her: all defiant trunks and branches, but few leaves.

The paintings reflect the ecstatic view she had of the forest – one painting that might have been called A Tree, is instead Happiness (1939, oil on paper). She bends the sky round the tree. She saw human attributes in trees. “It is a unique and special vision of hers, ” said Mr Dejardin. “In this gallery, you are looking at Emily Carr. You are looking at nobody else.”

Untitled (seascape), 1935. Oil on paper mounted on board. By Emily Carr. Art Gallery of Greater Victoria.

Sarah Milroy, a Toronto-based art critic who is joint curator, emphasised that the surrealists who were her contemporaries were just as deeply affected by the atmosphere of the northwest of Canada and its shores. There was an affinity although no visible connection.

Despite her frequent isolation, Emily was up to date with the latest trends: she was in touch with Canada’s renowned Group of Seven artists, her closest friend among them, Lawren Harris, telling her in 1927 “you are one of us.” Those words encouraged her take up her brushes again after several years of dispiritedness.

The following year she talked to the artists in Seattle, which was a hotbed of modernism. There are works in which she is toying with Cubism: most people would never recognise Emily Carr in those, said Mr Dejardin.

Emily Carr, Self-portrait, 1938-39. Oil on wove paper, mounted on plywood. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Gift of Peter Bronfman, 1990.

Her near-forgotten works in charcoal are included, and on display for the first time are the ‘momentary records, ’ sketches she left in a trunk for all to see after she died, including View in Victoria Harbour.

Many of her works betray a fascination with aboriginal totems, and Dulwich has set out cabinets with a total of 30 aretfacts including masks, baskets and ceremonial objects by local craftspeople, and on loan from Damien Hirst’s Murderme Collection (the contemporary UK artist is an aficionado of totem poles) and Horniman Museum and Gardens.

From the Forest to the Sea: Emily Carr in British Columbia encompasses more than 140 works, and includes the recently discovered illustrated journal, Sister and I in Alaska, a chronicle of her 1907 trip along the northwest coast. The exhibition is organised by Dulwich Picture Gallery and the Art Gallery of Ontario in collaboration with the National Gallery of Canada, Vancouver Art Gallery and the Royal BC Museum, BC Archives.

Blunden Harbour, c 1930. Oil on canvas. By Emily Carr. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa.

A Haida hereditary chief and master carver and sculptor, James Hart, launched the exhibition with a traditional Haida dance. The Haida people have struggled against the British Columbia provincial government to assert what they see as their rights in the territory they call Haida Gwaii (otherwise known as the Queen Charlotte Islands), an archipelago on the north coast, .

From the Forest to the Sea: Emily Carr in British Columbia Exhibition runs from November 1 2014 to March 8 2015. www.dulwichpicturegallery.org.