Straight, 2008-12. Steel reinforcing bars.by Ai Weiwei. Lisson Gallery, London/image and copyright the artist.

Triple challenge as outspoken Chinese artist Ai Weiwei prepares to ship work to London for Royal Academy solo show in September 2015, By James Brewer

One of the greatest living artists, Ai Weiwei, is hard at work in his Beijing studio preparing for a huge exhibition of his output at London’s Royal Academy of Arts starting in September 2015. The challenges for the show are threefold – artistic, political, and logistical.

The artistic test is that the dissident has yet to complete some of his ambitious projects for the London event, which will attract worldwide interest.

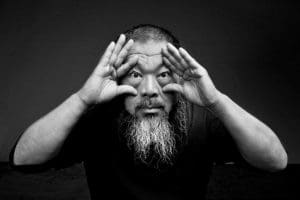

Ai Weiwei in his studio in Caochangdi, Beijing. Photograph April 2015 Harry Pearce, Pentagram.

The political predicament revolves around hopes that the artist, who has had his movements restricted for five years and his passport confiscated, will be allowed to travel to the UK; some observers believe the Chinese authorities may be softening their attitude as they recently sanctioned an exhibition of his work in their capital. Ai Weiwei is known for mocking his detention as though it were part of a grand episode of ‘performance art.’

The logistics task will be sending to the UK a large part of his most physically substantial work. Subject to Customs and other permissions, this needs to be shipped by container 12, 600 nautical miles. As such a voyage will take around 52 days the goods will have to be loaded on board shortly after mid-July.

Normally, curators seek to despatch art and museum artefacts by sea wherever appropriate, as the freight charges are considerably lower than on aircraft, but the sheer size and nature of the installation in question here means that ocean transport is the only option.

Surveillance Camera, 2010. Marble. By Ai Weiwei.Courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio. Image and copyright the artist.

Called Straight, 2008-12, the installation is part of a series stemming from the Sichuan earthquake of 2008, a catastrophe in which sub-standard building work was blamed for much of the huge death toll of around 70, 000.

Ai Weiwei asked his team to collect 200 tonnes of twisted and bent rebars (a frequent cargo on merchant ships: steel rods used for reinforced concrete buildings) and get them to his studio, where they were straightened out by hand. The bars would otherwise have gone into an industrial recycling mix.

The resulting artwork is a dense array of 150 tonnes of steel laid out to symbolise seismic waves and cheap housing construction methods: a sombre monument of silent contemplation of the victims of the quake. This is in line with a recurring theme for Ai Weiwei: the subject of destruction, whether by demolition or natural disaster.

Co-curator Adrian Locke said that the Academy would be able to show 90 tonnes of the colossal composition, and it would be the largest object the institution has ever handled. It is to be situated inside gallery III, which means the in-house architects and engineers must ensure the flooring is structurally sound enough to bear it.

Free Speech Puzzle, 2014. Hand painted porcelain in Qing dynasty imperial style. Courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio. Image and copyright the artist.

Details of shipping this and a good deal of other work from the studio have yet to be finalised, but Tim Marlow, Royal Academy artistic director and co-curator, said “we do not envisage problems with the authorities. He is working up to deadline and is still having ideas. So there is this sense of excitement until the shipment arrives.”

Ai Weiwei is to be celebrated as an Honorary Royal Academician in what is described as the first major institutional survey of his artistic output. He will create new, site-specific installations and interventions to be placed throughout the Academy premises.

Sponsorship for the show comes from London jewellery company David Morris of New Bond Street, just round the corner from the Piccadilly base of the Academy.

Considering this as primarily an artistic venture, the Academy has yet to have contact with the Chinese authorities and embassies, although Mr Marlow and Mr Locke have travelled to Beijing for discussions with the artist in his compound. Mr Marlow said of the artist: “He is eloquent and there is an extreme charisma about his physical presence. He is incredibly smart and there is a generosity of spirit about him that I find touching. I sense an inner sadness. I don’t think he wants to be in the position he is.”

Coloured Vases, 2006. Neolithic vases with industrial paint. By Ai Weiwei. Courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio. Image and copyright the artist.

Mr Marlow said: “He really does not see the world in black and white, ” and his artistic gestures “speak for themselves in complicated, layered ways” and were “not reducible to one definitive interpretation.”

Ai Weiwei’s work has been rarely seen in Britain (apart from his installation Sunflower Seeds at Tate Modern in 2010), and the Royal Academy will present works from the period since 1993, the date he returned to China following more than a decade in New York. In 2011, he was jailed for 81 days by the Chinese authorities, and later slapped with a huge tax bill, which was met by unsolicited donations from around the world. In an act of support from fellow artists and architects, he was elected an Honorary Member of the Royal Academy in May of that year.

“Will he come to London – unlikely, but we should be honoured if he did, ” said Mr Marlow. “I do not think it is as straightforward as him getting a passport.”

Mr Marlow said that in his home country “in public places, it is amazing how many people come up to him and express admiration.” Mr Locke added that his oeuvre was “not that visible in China, but you cannot contain him in the conventional sense. He is breaking these barriers.”

Mr Locke said: “Working with Ai Weiwei has presented us with new challenges but his ability to comprehend space, even without having experienced it first hand, and the clarity of his vision for the use of that space in relation to his work has been revelatory. A lot of what we want to show is under wraps [at present].”

Ai Weiwei. Photo copyright Gao Yuan.

As far as possible the artist, who is taking an architectural approach to the layout, is keen to take responsibility for the show. He has ‘navigated ‘the spaces available by means of video footage of the galleries and architectural plans.

It is still a show in progress, said Mr Marlow. “All artists like to work as close to deadline as possible.”

This exhibition is part of a series in which the Academy works with major artists to make landmark monographic shows, thus ranking Ai Weiwei with the likes of Anish Kapoor, David Hockney and Anselm Kiefer.

The Chinese artist creates new objects from old, ranging from Neolithic vases (5000-3000 BC) to Qing dynasty (1644-1911) architectural elements and furniture, thus questioning conventions of value and authenticity in modern China.

He buys vessels in markets and from antique dealers, aware that they might be fakes, but this interests him since they involve the same skill and traditions used to create the originals. In Coloured Vases, he poses the question whether a Neolithic vase newly dipped in paint is more valuable as a contemporary artwork than the original. This tension between the ancient and modern exemplifies his concern at the elimination of old residential areas by the relentless pace of development in Beijing and other mega-cities.

Marble sculptures such as Surveillance Camera, 2010 and Video Camera, 2010, ape the technology used to monitor him and others. There are some 20 cameras on buildings and telegraph poles around his compound (he has attached a red lantern below each one), and in the sculptures he figuratively “turns the camera back on the authorities.” The use of marble refers to the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) custom of tomb offerings of everyday objects made from precious materials.

In Free Speech Puzzle, porcelain pieces that together form a map of China are inscribed with the phrase ‘free speech, ’ a nod totraditional pendants that bore the name of a family and marked status and good fortune.

A new work, Remains, 2015, commemorates the suffering of his father and thousands of others during the regime of Mao Tse-tung. Replicated in porcelain are bones recently excavated at the site of a 1950s labour camp. In 1958, when Ai was a child, his father, the poet Ai Qing, was denounced during the so-called Anti-Rightist Movement aimed at silencing intellectuals, and with his family sent to a squalid military re-education camp until 1976 when he was rehabilitated.

The decision to undertake the exhibition was taken in August 2014 after conversations with friends and supporters of the artist at the Lisson Gallery in London. Mr Marlow went to see him in September, at which time the show was confirmed.

Ai Weiwei said that he was honoured to have the chance to exhibit at the Royal Academy in London, “a city I greatly admire.” Of his concepts and campaigns, he declares: “It’s not my choice, it’s my life.”

Ai Weiwei, at the Royal Academy, London, will run from September 19 to December 13 2015. Late night opening will be on Fridays until 10pm.