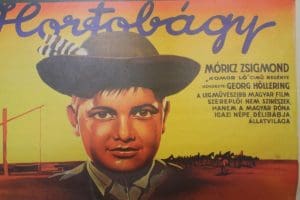

Poster for the 1930s film Hortobágy.

Captured for all time in the once-censored film ‘Hortobágy’: traditional pastoral life in the Hungarian plains

By James Brewer

It is just over 80 years since George Hoellering, an Austro-Hungarian producer, led a small movie crew to the Great Plain of Hungary to put on celluloid aspects of a 1, 000 year-old way of life.

The pastoral traditions of the vast prairie had never before been recorded on film.

Hoellering thus turned out a historic motion picture – and shortly afterwards the turbulence of 1930s Europe saw him re-establish himself in the totally different arena of London, where after some upsets he was to become a towering figure in the British film industry.

Despite critical praise as one of the best cinema productions of the epoch, the movie was initially spurned by Hungarian distributors, and mauled by the censor. Quality asserted itself over the years, though, and Hortobágy (named after the region that is the essence of Great Plain history, and released in the US in 1940 as Life on the Hortobágy) exerted widespread influence on European film-makers.

The ideal way to appreciate the true value of the 1936 masterpiece is to visit the heartland it celebrates and to absorb the background spelled out in displays in the eponymous museums of the place.

Part documentary, part fiction, the 79-minute production features ‘real people’ tending their sheep, cattle, and horses, and gives a fine sense of the seemingly endless Puszta landscape.

Hoellering (1897-1980) had moved away from Berlin where he had worked on documentaries from the early 1920s after the Nazis gained ascendancy. The notion of the Hortobágy film matured as he was chatting in a café in Switzerland or Austria with the cameraman László Schäffer, who had been central to the much-praised Berlin – Symphony of a Great City, a movie which portrayed a day in the life of the bustling metropolis.

Horsemen of the plains.

In this new task, Schäffer “recorded everything in black-and-white shots of extreme beauty, ” wrote András Szekfű of King Sigismund College, Budapest in an article for the International Research Institute s.ro. which is based in Komárno, a River Danube port which straddles the Hungarian-Slovak border.

Hoellering’s initial conception for Hortobágy was to make a kind of instructional documentary, ending with a commentary about international capital exploiting the shepherds, wrote Dr Szekfű, but having spent a summer among the people of the plains, he rather wanted to show the traditional way of life there, and the eternal circle of conception-birth-life-death, of sunrise and sunset.

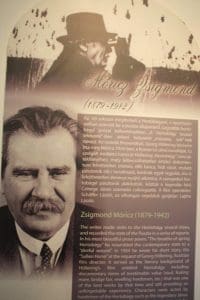

Hoellering realised that to reach wider audience for the film, he needed to incorporate a storyline, and approached Zsigmond Móricz (1879–1942) a Hungarian realist novelist who had been writing about the hard life of the peasantry.

The final version of Hortobágy is based on the story Komor Ló (Sullen Horse), in which a young woman who loves an impecunious herdsman rebels against being forced to marry a rich peasant.

Hungarian composer László Lajtha (1892-1963), a close colleague of Bartók in folk music research, added symphonic music including a section entitled Gallop and Storm, and folk songs for soloists and a shepherd choir.

Dr Szekfű tells how the censors ordered four cuts to Hortobágy as a condition for a Hungarian premiere, although they allowed the full version to be exported. They called for the removal of the mating scenes of horses, the mating scenes of storks, the birth of a foal and the burial of a horse.

Despite positive press reviews, the film ran for only a week in two Budapest cinemas. Sándor Márai, the great Hungarian novelist and playwright who saw the uncut version, wrote an entire newspaper column about it.

The novelist Zsigmond Móricz.

The film became part of the cinematographic memory of Hungary, wrote Dr Szekfű, and in later decades it was shown at universities, on film courses, and several times on Hungarian television.

Hoellering brought with him to England Hortobágy and a premiere was organised in December 1936 in the New Gallery Cinema. Graham Greene wrote about it in the Spectator, saying: “Undoubtedly, the horses have it. Hortobágy, a film of the Hungarian plains, acted by peasants and shepherds, is one of the most satisfying films I have seen.”

In mid-1940, Britain interned Hoellering for several months in a camp for ‘enemy aliens’ on the Isle of Man, where he wrote and directed an amateur performance of a musical called What a Life! After his release, he was able to revive his career triumphantly, and from 1944 he was a leading personality in the British film industry, as distributor and co-owner and managing director of the Academy Cinema at 167 Oxford Street.

Posters from the 1930s advertising Hortobágy are on display in the Csárda Museum within the premises of the Hortobágy Big Inn. Nearby, the Hortobágy National Park Visitor Centre and Craftsmen’s Yard give insights into traditional life, and the social and ecological story of the Puszta, showing how livestock breeding through grazing plays an essential role in maintaining the flora and fauna in saline soil.

The lives of the herdsmen are traced: how their ancient reed and adobe homes were simple but practical, and how the sweep-pole wells for watering the animals have become symbols of the landscape.

One of the most intriguing traditions recalled is the five-in-hand coach parade in the city of Debrecen. The museum lists famous passengers over the year, starting with Lajos Kossuth, champion of Hungarian independence, in 1849; and Emperor Franz Josef of Austria, king of Hungary (1830-1916) in 1852 and 1890.

Hortobágy leather craftsman.

Other illustrious names in the Debrecen parade included in 1918 Charles IV of Hungary (1887-1922), the last ruler of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and last King of Hungary, who had become became heir presumptive after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo in 1914. Charles succeeded to the thrones in November 1916 after the death of Franz Joseph.

Admiral Miklós Horthy (strongman Regent of the Kingdom of Hungary and briefly commander-in-chief of the Austro-Hungarian Navy until its dispersion) joined the parade in 1928; and Prince Edward Duke of Windsor (who had reigned as King of Britain before abdicating at the end of 1936) in 1937.

Delving much further back in history, it is hard to imagine the scene posited by the Hortobágy museums that 12m to 14m years ago most of the Carpathian Basin was under Lake Pannon, which dried up by the end of the tertiary period (2.4m to 5m years back).

A Pannonian sea was once connected to the Mediterranean through the territories of the modern Ligurian Sea, Bavaria, and Vienna Basin; through the Đerdap Strait (or Iron Gates, a gorge on the Danube), to the Paratethys – a large shallow sea that stretched from north of the Alps to the Aral Sea in Central Asia ; and to the Aegean Sea.

From the end of the Ice Age, much of the Hortobágy was a flood area for the rivers Tisza and Berettyó, until the water regulation took place in the 20th century.

One way to experience a sense of 19th century Hortobágy pastoral life, is by searching for a free version on the internet of the 1893 novel The Yellow Rose by Jókai Mór (1825-1904) about a cowherd who “In the wide upturned brim of his hat… wore a single yellow rose.” It was a time when “no train crossed the Hortobágy, when throughout the Alföld [Great Plain] there was not a railway, and the water of the Hortobágy had not been regulated.”