Royal Academy’s new show: Bill Viola/Michelangelo: Life, Death, Rebirth

By James Brewer

In what might strike some people as an odd pairing, the Royal Academy of Arts has put together in one spacious show productions of the California-based video artist Bill Viola (born in New York in 1951) and drawings by Michelangelo (born in a Tuscan village in 1475, died in Rome in 1564).

Michelangelo’s studies are intimate and tender, as is his poetry. Viola’s narrative is raw and confrontational, his installations often room-sized.

Consider a few verses from the Italian Renaissance artist which are printed on the gallery walls for this exhibition.

This from 1524: “Alas, Love, how swift to act you are, reckless, bold, armed and strong! /For you drive out of me all thought of death at the time when it is approaching/ and from a withered tree draw foliage and flowers.”

On the brink of death, Michelangelo considered his life to be like a fragile barque crossing a stormy sea to the great port where all are in the end summoned.

Although many of the works of Viola, like those of the brilliant master who first flourished under Florentine patronage, explore the passage between life and death, entwining the achievements of the two men could be considered an artificial construct.

Many visitors to the Royal Academy will find that at least initially the modest-scale compositions of Michelangelo overwhelm the huge Viola video screens.

It takes a while and a leap of thought process to discern how and why these figures working five centuries apart and in the different media of their times, could or should be made to sit alongside each other. The rationale given is that the men share a deep preoccupation with the nature of human experience and existence – although that is in the DNA of most men and women across all fields of the arts.

Bill Viola/Michelangelo: Life, Death, Rebirth is said to create an artistic exchange between the two artists. The juxtaposition is billed as “a unique opportunity to see major works from Viola’s long career and some of the greatest drawings by Michelangelo together for the first time.” Note that it seems to be in the nature of the presentation that Viola gets the first billing.

Viola, who is an Honorary Royal Academician, encountered the works of the Italian Renaissance in Florence in the 1970s. A residency at the J Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, in 1998 renewed his interest in what he saw as the period’s shared affinities with his own practice. The catalyst for the current exhibition came in 2006, when he visited the Print Room at Windsor Castle to see first-hand Michelangelo’s drawings, and this has turned into “a conversation” between him and Martin Clayton, head of prints and drawings at Royal Collection Trust.

What would Michelangelo have made of being posed in a double act in the first exhibition at the Royal Academy largely devoted to video art? He might have enjoyed the experiment, for he was a bold and unashamed depicter of big ideas and emotions, whether from the Bible or from Greek myth. Viola’s “canvas” is rather narrower but at least he has been regarded as a pioneer in his artform.

In 1985, Viola wrote: “I live in the last part of the 20th century, and the medium of video (or television) is clearly the most relevant visual art form in contemporary life. The thread running through all art has always been the same.”

Viola was one of the first artists to have conceived video on an immersive, architectural scale. The Royal Academy says he has” increasingly utilised his medium’s fundamental elements – light, sound and time – to create visceral works that consider metaphysical questions about the nature of existence and reality. Unusually for video, they give shape to inner states of being rather than mirroring the world around us.”

Viola is quoted as saying: “Through my travels and experiences first in Florence, then primarily in non-Western cultures, and in combination with my readings in ancient philosophy and religion, I began to be aware of a deeper tradition, an undercurrent stretching across time and cultures… the ancient spiritual tradition that is concerned with self-knowledge.”

The exhibition sets out to examine the affinities between the protagonists, offering “specific works to explore resonances in their treatment of the fundamental questions: the nature of being, the transience of life, and the search for a greater meaning beyond mortality.”

As videos demand the dark, visitors must quickly become accustomed to the gloom – lights out starts in the enormous central hall of the Academy with one of Viola’s large, slow-motion projections, The Messenger, a naked man rising and sinking from water that intimates the cycles of birth and death.

In all there are 12 video installations by Viola, from 1977 to 2013, and 15 works by Michelangelo, the latter organised in partnership with Royal Collection Trust.

The show serves as a reminder that the 16th century genius, known in his lifetime as Il Divino, found time in between painting the Sistine Chapel, creating huge sculptures and being the architect of St Peter’s Basilica, for drawing and for poetry, penning more than 300 sonnets and madrigals. The poetry took a back seat in succeeding years, as it betrayed his homosexual leanings, covered up by nervous translators and commentators.

Fourteen finished drawings, considered the high point of Renaissance drawing in technical and design virtuosity and aiming to recapture his spiritual and emotional core, here are supplemented by The Virgin and Child with the Infant St John the Baptist, from 1504-05, known as the Taddei Tondo, from the Royal Academy’s permanent collection.

The sculpture acquired its name from a commission by a wealthy cloth merchant Taddeo Taddei. Tondo is a Renaissance term for a circular work of art.

In the tondo, St John the Baptist touchingly presents a bird to the infant Christ, who turns towards the Madonna. The bird has been identified as a goldfinch, representing Christ’s suffering before the Crucifixion – one of this species removed a thorn from His crown as He was carrying the cross.

Opposite is the Nantes Triptych of 1992, courtesy of Bill Viola Studio, in which the first of three screens shows close-up and the pain of a woman giving birth, the central screen a figure floating in a mysterious light, and the third has Viola’s mother on her deathbed. Viola comments: “It is the awareness of our own mortality that defines the nature of human beings.”.

The works of Michelangelo chosen are said to reveal a personality that was frequently vulnerable. They were executed in the last 35 years of his life, some as gifts and expressions of love for close friends, others as private meditations on his own mortality. The religious imagery reflects on the presence of death and the eternal, while there are stories from Classical mythology as metaphors for the human condition.

Michelangelo produced his ‘Presentation Drawings’ of the 1530s (loaned by the Queen from the Royal Collection) as gifts for Tommaso de’ Cavalieri, a young Roman nobleman for whom he developed a strong affection. They act as demonstrations of the craft of drawing with chalk.

They include in black chalk Tityus, 1532, which is an allegory for the aspects of Neoplatonic philosophy: there is savage punishment for lust devoid of spiritual love – for an attempted rape, Tityus is chained to a rock in Hades, the ancient Greek underworld, and is tormented violently.

Also in black chalk are illustrated the toils of Hercules and the fall of Phaeton, from 1533. Three labours of Hercules show him slaying in turn the Nemean lion, the giant Antaeus who was the son of Poseidon and Gaia, and the many-headed Hydra.

Others lent by the Queen include the finely-preserved, red-chalk A children’s Bacchanal of 1513. This remarkable scene shows children revelling in debauchery, with a deer being carried to the pot and a drunken adult man at lower right and a female satyr at lower left. The children represent the soul in the absence of reason or intellect, when humans are driven by base urges to act like animals.

At the other end of the age scale, Viola’s Man Searching for Immortality/Woman Searching for Eternity is a slow 19 minutes of an elderly man and woman, their images projected onto two black granite slabs, examining their naked bodies by torchlight, half-ashamed and unable to hide from the pass they have got to.

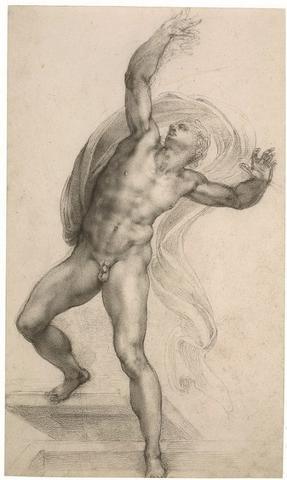

Finally, what of the possibility of rebirth? Michelangelo has here two Crucifixions executed in the final years of his life. Already in 1530, Michelangelo made more than a dozen drawings of the Resurrection or the Risen Christ. It has been suggested that the Risen Christ drawing on show was a study for a Resurrection in the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel, but it might have been intended as a finished work. Royal Collection Trust says that in no other work by Michelangelo is the resurrection of Christ expressed with such glorious exuberance.

The exhibition has a blockbuster close to its perhaps overwrought journey through the transience and tumult of existence and the question rebirth, with Viola’s monumental projections Fire Woman, 2005, and Tristan’s Ascension (The Sound of a Waterfall Under a Mountain), 2005. They depict bodies falling and rising out of view, in different ways conjuring the body’s final journey and the passage of the spirit, in obscurity or in glory.

The real last word goes to Michelangelo, who around1552-54 decided: “My life’s journey is finally arrived/ after a stormy sea in a fragile boat/ at the common port through which all must pass/ to render an account of every act, evil and devout.”

The exhibition is curated by Martin Clayton of Royal Collection Trust; with Kira Perov (Viola’s wife) who is executive director of Bill Viola Studio; and Andrea Tarsia, curator at the Royal Academy.

Captions in detail: Fire Woman. Video/sound installation by Bill Viola,2005. Performer: Robin Bonaccorsi. Courtesy Bill Viola Studio. Photo: Kira Perov.

The Virgin and Child with the Infant St John. Marble relief, c 1504-05. By Michelangelo. Royal Academy of Arts, London. Bequeathed by Sir George Beaumont, 1830. Photographer: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd.

Tristan’s Ascension (The Sound of a Mountain Under a Waterfall). Video/sound installation by Bill Viola, 2005. Performer: John Hay. Courtesy Bill Viola Studio. Photo: Kira Perov.

The Risen Christ. Black chalk on paper, c 1532-3. By Michelangelo. Royal Collection Trust. C Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019.

The Lamentation over the Dead Christ. Black chalk, c 1540. By Michelangelo. The British Museum, London. Exchanged with Colnaghi, 1896. C Trustees of the British Museum.

Nantes Triptych. Video/sound installation, 1992. Courtesy Bill Viola Studio. Photo: Kira Perov.

Bill Viola/Michelangelo: Life, Death, Rebirth in the Royal Academy main galleries runs from January 26 to March 31 2019, 10am- 6pm daily, but Fridays until 10pm.