Van Gogh and Britain: a star-studded spectacular at Tate Britain

By James Brewer

Behind Vincent van Gogh’s expression in luxuriant brushstrokes of the unflinching energy he identified in nature is a large helping of the creativity he drew from his experience of British life and literature. His eager curiosity and insights into society were heightened by two years spent in London and southeast England. That was a foundation for his ardent style, triumphantly conveying the temperament of the common man and woman, the sturdiness of trees, an empathy for the seeming eternity of the stars.

His impulse to take as subject matter his downtrodden fellow citizens and everyday objects around him underline the compassion and fellow feeling of the man who would become one of the greatest artists of all time.

His relationship with the country to where he was for a while an immigrant is presented in absorbing manner by The EY Exhibition: Van Gogh and Britain which is mounted at Tate Britain. A route through nine dedicated rooms acquaints us closely with someone who in his brief life set revelatory standards for the whole era of modern art. This is the eighth exhibition supported through the EY Tate Arts Partnership between the gallery and the consultancy in assurance, tax, transaction and advisory services. The spaciously laid-out show relates Britain’s influence on van Gogh, and in turn his influence on subsequent generations, right up to the present, of British artists.

In pithy but illuminating captions, the gallery offers acute insights into van Gogh’s perceptions. They draw attention for instance, in one of the many scenes painted in the walled gardens of the psychiatric clinic where van Gogh stayed from May 1889 to May 1890, to the contrasting red earth and green leaves. The curators say: “The trees swirling high above the hospital buildings express the energy he found in nature.” From the courtyard he brings out “the proud unchanging nature of the pines and the cedar bushes against the blue.”

The comment refers to one oil painting, A view of the garden at the Hospital at Saint-Rémy, loaned by the Armand Hammer Museum of Los Angeles, but is apposite to many. At the sanatorium, to which he had the intellect to admit himself voluntarily, he made the most of his picturesque surroundings by recording them in 150 paintings.

In works such as that garden view, his bold colours and brushwork bring closer to the viewer the rugged and characterful trees. He was building a bridge between human beings and nature. The critic Darran Anderson has referred to the “rough seas of flowing colour” in such canvases.

Notwithstanding or because of all that has been written about Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), it is abundantly clear from this survey of much of his life that he was shot through with honesty. Intelligence and generosity. The decades-old caricature of him as an irrational lunatic lies in the dust.

Like Charles Dickens, whose writings he devoured, he spent hours walking through the teeming streets of London and pounding over its bridges, observing the under-side of society, although in his case mostly it was a commute to work (at an art dealership in Covent Garden) rather than a matter of restless peregrination. ‘My whole life is aimed at making the things from everyday life that Dickens describes and these artists draw,” he wrote as he turned increasingly to exercising his pictorial vision.

He was moved by the plight of men and women struggling to get food to the table in London and on the near-Continent. While today he is best known for his essays in vivid impasto style, many of which are on display at Tate, it is the smaller, “minor” works that serve to reveal the essence of the man and the breadth of his outlook.

These slighter efforts are modelled on his enthusiasm for British graphic artists and prints. He spent much of his time and money on collecting around 2,000 engravings and magazine illustrations from the Illustrated London News, and the subjects included refugees and soup kitchens. This resulted for instance in the graphite, chalk and watercolour study Public Soup Kitchen, the Hague, from 1883.

In the final months of his life, he returned to the style he had developed from prints, painting in oil his only image of London, The Prison Courtyard, which is based on a Gustave Doré engraving of the squalid Newgate Prison in the City. It shows the misery and hopelessness of the inmates, as a guard and two men in top hats supervise them. It is clear Van Gogh felt deeply for the social condition of the convicts. In this striking depiction, he deploys the strong brush strokes for tone as well as for colour, and to reinforce the circular motion of the parade of the wretched. This painting, borrowed from the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow, is placed next to the artist’s personal copy of the Doré print. Not quite everything is despair: there is a light source, perhaps from a gap in the wall or skylight in the top left-hand corner, where what could be two yellow butterflies flutter, in an echo of the original print. The insects are in yellow – his beloved yellow!

More than a century ago, the writer C Lewis Hind described van Gogh as “a madman and a genius,” a view echoed in some quarters to this day. Taking the opposite viewpoint, the dramatist and artist Antonin Artaud in 1948 published an article headed The Suicide Provoked by Society.

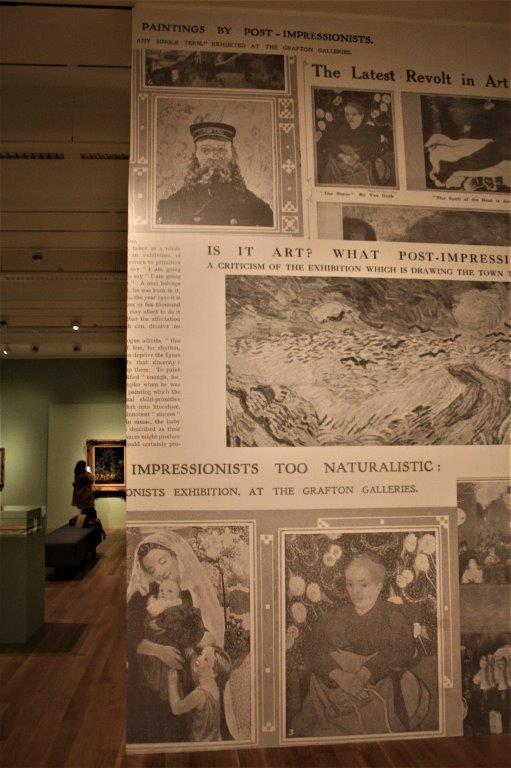

Tate carefully highlights the prejudice around mental health when he and other “post Impressionists” were ridiculed in the early 20th century (“Is it art?” sneered one reviewer) and separates the man from the stigma. How could anyone dismiss a person who in just over a decade created about 2,100 works, including around 860 oil paintings, most of them in the last two years of his life, and many among the most loved artworks in the world.

The curators assemble from public and private collections the largest group of van Gogh paintings shown in the UK for nearly a decade, including more than 50 by the artist.

This tribute to the personally modest master ought to help brighten the national mood in Britain in 2019 amid what some call the “nightmare” of the Brexit debacle. His heritage achieved just such a sunny result in 1947 when the Tate exhibited 177 of his paintings and drawings. A daily average of 5,000 people who had lived through the grey years of war lined up patiently during a rainy December to inspect what was dubbed “the miracle on Millbank,” a reference to Tate’s Thames-side address.

In the weeks that followed, van Gogh’s dazzling colours spiced with blades of light went on to cheer the residents of two other war-ravaged cities, Glasgow and Birmingham. The concept of van Gogh as “an artist of the people” chimed with the post-war mood and the ideals of “art for all,” says a commentary in the current exhibition. Newspapers attributed the success of the 1947 show to the fact that people had been “colour-starved” by wartime austerity.

Van Gogh was in London between 1873 and 1876, writing to his brother Theo, “I love London” before he turned his back on commercial life.

After working in The Hague for his uncle as a trainee with international art dealer Goupil & Cie Vincent had been sent to London at the age of 20, and revelled in life in the metropolis, especially his visits to the Royal Academy, the British Museum and the National Gallery where he drank in the output of John Constable and the Pre-Raphaelites including John Everett Millais, and French countryside painters such as Jean-François Millet and Jules Breton.

Seeing these impressive exhibits prompted van Gogh later to entitle some of his works in English in the hope that they would secure British buyers.

English was one of four languages he spoke, and his time in London enabled him to further his appreciation of great literature, from William Shakespeare to Christina Rossetti. He continued to read Dickens until his death. L’Arlésienne (sourced from the Museu de Arte de Säo Paulo), a portrait created in the last year of his life, has a favourite book, Christmas Stories by Dickens, in the foreground.

“Reading books is like looking at paintings,” he wrote. “One must find beautiful that which is beautiful.” In his letters, van Gogh mentions more than 100 books by British authors, and Tate sets up a vitrine of copies of such books. The writers include George Eliot, whose novel Middlemarch, influenced van Gogh’s desire for social reform.

He delighted in Pilgrim’s Progress, an allegory by John Bunyan of a traveller facing obstacles along his path that test his faith. The metaphor is seen in many of his drawings and paintings.

Britain offered him a measure of prosperity. He bought a top hat, a symbol of the successful middle-class. He lived in south London, first in Brixton and then in Oval, about 2 km south of the Tate building, walking over Westminster Bridge on his way to work, and observing ships ply their trade. “I crossed Westminster Bridge every morning and evening and know what it looks like early in the morning, and in the winter with snow and fog.” He travelled on the river by boat – and on the underground railway.

“The van Gogh we know was being born in London,” says Tate Britain director Alex Farquharson. “Britain was instrumental in shaping the van Gogh we know today.”

Van Gogh admired Doré’s The Houses of Parliament by Night for capturing what he saw as the magic of London. In Starry Night Over the Rhoneof 1888 he sought to replicate the spectacle of a riverine city at night, a view of Arles as its shimmering lights ripple across the water. Perhaps he wanted to celebrate the depth of the universe, more than just reproduce a nocturnal scene. It is an evocation of the music of the spheres that has everlasting resonance.

It is thrilling to see Starry Night close-up and if viewed obliquely it is seen to be richly embellished by ridged layers of pigment. Van Gogh had the technical awareness that colours needed to be liberally applied if they were to remain fast, for artists were not always able to afford the more durable high-quality materials.

During his time in London, much-needed social reform was a burning topic. Upset by the poverty evident on the streets of London, he began to question the system, and strive for a meaningful life. He was transferred to Paris and became increasingly religious, volunteering as a pastor in Borinage, a mining village in Belgium. His superiors in the Church were angered by his philanthropy and ousted him for challenging their authority.

After leaving the Church he joined the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. At the age of 27, with the encouragement of his brother, he set course to become an artist, starting his prolific career.

He determined to create art “for the people,” an ideal inspired by George Eliot’s radical outlook. Van Gogh’s work was not considered saleable, but in any event it is doubtful that he wanted to profit from the paintings that were to be valued in the millions of dollars after his lifetime,

His sympathy for the exploited in society is reflected in his full-length portraits of seamstresses at their lonely piece-work, one such woman depicted in chalk, wash and watercolour with a shy cat at her feet.

He loved the south of France, writing of Provence: “the stronger light, the blue sky, teaches one to see.” Those are words that might have been spoken by David Hockney – one of today’s greatest living artists – who urges his fellow exponents to open their eyes to colour even in the drabbest of surfaces. This is surely the justification for staging a concurrent exhibition, Hockney – van Gogh: The Joy of Nature, at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam until May 26, 2019.

The brave juxtaposition with Hockney seems logical after concentrating for, say, three hours at the Tate on van Gogh and his legacy: both men make the viewer feel they are in the presence of the vibrant reality of nature; both are uncompromising in sharpening its visual impact.

Look for example at the 1889 oil painting Olive Trees lent by the National Galleries of Scotland which was shown at the first solo exhibition of van Gogh in Britain in 1923. This is one of 15 canvases he painted of such trees while at Saint-Rémy. He wrote: “The effect of daylight and the sky means there are endless subjects to be found in olive trees. For myself I look for the contrasting effects in the foliage, which changes with the tones of the sky.”

He saw the biological process of the species as analogous to human life. The Scottish gallery says of Olive Trees: “The writhing brushwork and strident colours contribute to the painting’s powerful impact. Van Gogh was fascinated by the gnarled structures and changing colours of olive trees. He was also fully aware of their association with the story of Christ’s Passion and the episode of Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane on the Mount of Olives.”

Of one painting (there are five versions of the subject) he wrote that he could “imagine it cheering the cabin of a sailor far from home.” This is his 1889 portrait of Augustine Rouline rocking a cradle (La Berceuse) and we are shown the example held by the Stedelijk Museum of Amsterdam. Mme Rouline is shown in exaggerated colours against a vividly patterned background, hands tending the reins of a cradle.

Despite its familiarity, Sunflowers in all its glory dramatically lights up one of the Tate rooms, out-powering the neighbouring flower compositions it inspired among British artists. The Britons saw what was to become one of the most recognised paintings of any genre anywhere when it was exhibited in London in 1910 and 1923. He had painted Sunflowers to decorate a room for his friend Paul Gauguin in the yellow house he rented in Arles, where he briefly attempted to set up an artists’ colony. Rarely is this painting loaned by the National Gallery, even to fellow London galleries.

“Modern European art,” said the Bloomsbury Group artist and critic Roger Fry in 1910, “has always mistreated flowers, dealing with them at best as aids to sentimentality, until van Gogh saw… the arrogant spirit that inhabits the sunflower.”

Other works on show include the 1889 Self-Portrait from the National Gallery of Art, Washington, Shoes from the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, and At Eternity’s Gate (made in the Saint-Paul asylum) from the KröIler-MüIIer Museum, Otterlo. A new movie based on his life takes the title of the last-named picture. At Eternity’s Gate has an old workingman by the fire with his head in his hands and elbows on his knees. It was completed when the painter was convalescing some two months before his suicide.

Another late work – from the Tate Collection – is the delightful Farms near Auvers, a town on the Oise north of Paris where he spent the last few months of his life. This oil painting although unfinished is far from a farewell note.

The exhibition adds an opportunity to look afresh at works by van Gogh through the eyes of the British artists who followed him, sometimes entering into his spirit, sometimes reworking what they thought of as an outlier of the mainstream.

It posits that van Gogh paved the way for Walter Sickert, Matthew Smith, Christopher Wood, David Bomberg, Vanessa Bell, Frank Brangwyn and Francis Bacon. Harold Gilman (1876–1919) of the Camden Town Group had a reproduction of Van Gogh’s portrait in his studio to salute whenever he embarked on a work.

The exhibition is organised by lead curator Carol Jacobi, curator of British art of 1850-1915 at Tate Britain, and Chris Stephens, director of Holburne Museum, Bath, with van Gogh specialist Martin Bailey, and Hattie Spires, Tate assistant curator of modern British art, with support from James Finch, assistant curator of 19th century British art at Tate.

One of the most touching testimonies here of van Gogh’s celebration of bold colour is a facsimile of an illustrated letter he sent in 1888 from Arles to the Australian artist John Peter Russell. He writes of visiting “a great field, all violet and the sky blue, and the sun very yellow… Yours very truly, Vincent.”

This exhibition itself is… very truly a masterpiece in art.

Captions to selected images in detail:

The Prison Courtyard, 1890. Oil on canvas. Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow.

Starry Night, 1888. Oil on canvas. Paris, Musée d’Orsay. Photo (C) RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay)/ Hervé Lewandowski.

Olive Trees, 1889. Oil on canvas. National Galleries of Scotland.

L’Arlésienne, 1890. Oil on canvas. Collection MASP (São Paulo Museum of Art). Photo João Musa.

Sunflowers. By Frank Brangwyn (1867–1956). Early 20th century. Oil on board. Lent by the Royal Academy of Arts, London. © Estate of Frank Brangwyn/ Bridgeman Images.

The EY Exhibition: Van Gogh and Britain runs until August 11, 2019 Tate Britain.