Natalia Goncharova: Tate Modern celebrates trailblazer of modern art

By James Brewer

She was the personification of the avant-garde before the avant-garde got into its ultra-provocative stride.

Outraging early 20th century Russian society, Natalia Goncharova (1881–1962) was later tucked away from mainstream history for many years.

A whirlwind of creativity, Natalia bravely challenged conventions in a heady but repressive Moscow. She came up against the stern grip of the Church, relished the sights of breakneck but creaky industrialisation, and played her own tune amid broader revolutionary upsurge.

She and her partner Mikhail Larionov indulged in a torrent of experimentalism which was eventually dubbed ‘everything-ism’ – before going on to a new role as a fashion designer, and originator of costumes and sets for radical Paris theatre and the Ballets Russes of Serge Diaghilev.

In is third floor area known as the Eyal Ofer Galleries, Tate Modern is staging the UK’s first retrospective of Natalia Goncharova, a captivating spectacle, brimming with pizzazz.

This section, endowed by the philanthropist Eyal Ofer, who heads real estate firms and the shipping business Zodiac, has hosted exhibitions of Matisse, Picasso, Edward Hopper, Gauguin and other luminaries. Goncharova has been ‘invited’ late to this distinguished company, and the Tate presentation more than remedies periods of neglect.

The cognoscenti picked up on her dazzling versatility just a few years ago. For a while this daughter of a provincial family was the most expensive female artist by auction sale, when an oil on canvas, Espagnole, painted around 1916, realised an above-estimate £6,425,250 at Christie’s in February 2010 in London. In 2017, her Still Life with Teapot and Oranges was sold by the same house for £2,408,750, more than triple the catalogue top estimate.

The Tate exhibition rejoices in Goncharova as the head of an avant-garde that preceded the ‘shock’ of such as Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square of 1915 and ingenious geometric constructions of that decade. Paradoxically, Goncharova began her long career inspired by the traditional customs, costumes and cultures of her native Tula province, 240 km south of Moscow. Introducing visitors to that early world she loved, the exhibition starts with a display of peasant costume and woodcuts.

She was the daughter of an architect who moved the family to Moscow when she was 10, but was deeply influenced by the rural way of life she admired. Her singular talent is immediately evident with the 1907-08 Self-Portrait with Lilies, from the State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, the source of many stunning canvases shown. This self-confident portrait emphasises her fondness for bold colours and dress. She is already importing from far afield wider cultural trends in Peasants Picking Apples, a neo-Primitivist depiction of the sturdy reliability of the multi-million-strong peasantry. Tretyakov in its description says that the figures are more like wooden idols as “a synthesis of her impressions from contemplating Scythian stone women [in southern Russia] and getting acquainted with African sculpture.”

From the same year of 1911 is the nine-part (two of the panels are missing) large-scale work The Harvest inspired by icons and church frescoes but in bright orange, yellow and red and other non-ecclesiastical hues, reflecting an interest in pagan imagery — a kind of Rite of Spring a couple of years before its premiere.

Underlining her observation of the encroaching machine age, The City shows modern apartment blocks with aeroplanes flying above a polluting factory chimney.

A four-panel work, The Evangelists was well received in a Post-Impressionist exhibition in London in 1912 but when it was put up in of St Petersburg in 1914 the authorities quickly removed it.

She had in 1910 shocked Moscow with female nudes in paintings of pagan mythology and was accused of obscenity. At the same time, she was producing individual but more acceptable studies such as Bread Seller and the Cubist-like Orange Seller.

Goncharova met Larionov when they studied at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. They shared a studio in the city, from where they unleashed their vast output. They reasoned: “We acknowledge all styles as suitable for the expression of our art, styles existing both yesterday and today.”

Their prolific reach encompassed painting, print, theatre design, fashion, interior design, book illustrations posters, lithographs, “sound poetry” and performance art. They founded radical groups named Jack of Diamonds, Donkey’s Tail and Target. Goncharova exhibited with Wassily Kandinsky, Malevich and Vladimir Tatlin.

Revelling in adventurous colours and patterns, they invented a genre known as Rayonism based on using dynamic rays of contrasting colour to echo the rapid pace of urbanised life

By 1913 Goncharova had enough material – more than 800 works – for a retrospective at the Mikhailov Art Salon in Moscow, which she updated for her solo exhibition a year later in St Petersburg, where her religious works were again censored.

It is easy to imagine from Tate’s sensational assemblage of its selections how her exhibitions must have struck the variously bemused and admiring viewers.

The first such exhibition by any member of the Russian avant-garde, the 1913 Moscow show confirmed Goncharova as a de facto leader of that unwieldy movement, ahead of Marc Chagall, Kandinsky and others who today have considerably more renown.

Nor was this based solely on gallery acclaim. She and like-minded colleagues treated Moscow to a taste of her performance art, painting their faces in futurist make-up and parading through busy thoroughfares to advertise – with great results – their event.

Goncharova’s experiments with the modernist styles of cubo-futurism, abstraction and rayonism, are highlighted in three works on show. Linen from Tate’s collection, Loom + Woman (The Weaver) from the National Museum of Wales and The Forest from the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art are from the same studio in 1913. They are on display together for the first time in more than a century. Linen conveys the hubbub of a commercial laundry and includes male shirts, collars and cuffs, and female (lace, blouses, aprons, perhaps a reference to the Goncharova-Larionov partnership. The Weaver shows a woman in headscarf bent over an industrial loom, illuminated by an electric light.

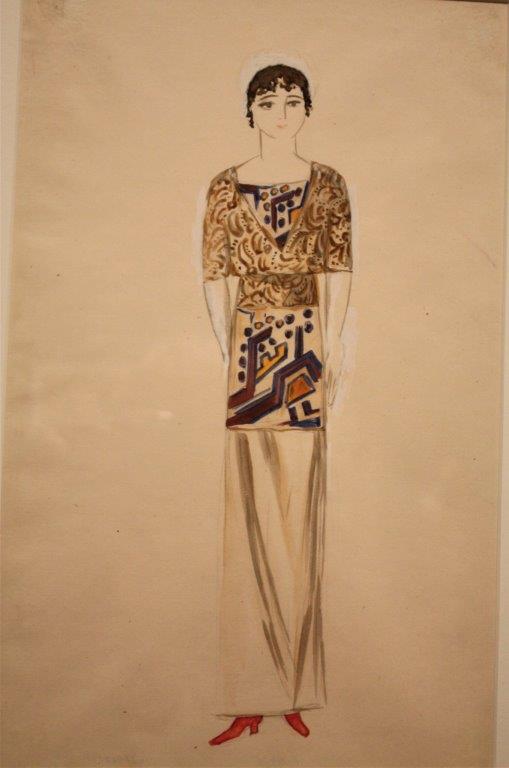

A section is dedicated to her fashion design, some of which reflect an interest in Byzantine mosaics, and her collaborations in 1912-13 with Nadezhda Lamanova, who unusually was a couturier in turn for the Tsarist and Bolshevik regimes.

Arriving with Larionov in Paris for a second time at the invitation of Diaghilev, Goncharova gained new fame with her vibrant costume and set designs for the Ballets Russes, and never returned home. She brought to the ballet sets a style fusing avant-garde concepts and her Russian heritage, as did her abstract fashion designs for the House of Myrbor in the French capital.

Diaghilev described her designs as “simply fabulous” and “exceedingly poetic.” She notably created sets and costumes for the opera-ballet Le Coq d’or and for Igor Stravinsky’s ballets L’Oiseau de Feu and Les Noces, neatly illustrated in paintings and film in a dedicated room at the Tate exhibition.

Her 1920s interior design is represented by the decorative screen Spring of 1928, commissioned by the Arts Club of Chicago and lent for the first time, and Bathers of 1922, a triptych having its first outing in the UK.

In all, the exhibition is an excitingly wild ride through pre-revolutionary Russia, spilling into post-war creative Paris, with the 170-plus loans a feast for the eyes and the intellect.

Natalia Goncharova is curated by Natalia Sidlina, curator of international art, and Matthew Gale, head of displays, with Katy Wan, assistant curator, Tate Modern. It is organised in collaboration with Palazzo Strozzi, Florence, where it will open on September 28, 2019, and the Ateneum Art Museum, Helsinki, where it will open on February 21, 2020.

Captions in detail:

Self-Portrait with Yellow Lilies. 1907-1908. Oil on canvas. State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. Purchased 1927. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019.

Nudes, 1911. Oil. State Tretyakov Gallery.

Bread Seller, 1911. Oil. Centre Pompidou, Paris, Musée Nationale d’Art Moderne.

Dress design for Lamarova fashion house, 1912-13. Graphite and gouache on paper. State Tretyakov Gallery.

Peasants Picking Apples, 1911. Oil on canvas. State Tretyakov Gallery. Received from the Museum of Artistic Culture 1929. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019.

Orange Seller. 1916, Oil on canvas. Museum Ludwig. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019.

Harvest: Angels Throwing Stones on the City. 1911. Oil. State Tretyakov Gallery. Bequeathed by AK Larionova-Tomilina 1989. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London.

Peasant woman. Costume design for Le Coq d’Or. 1937. Watercolour, bronze paint and graphite on paper. State Tretyakov Gallery. Presented by E Kurnan 1983© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019.

Set design for the final scene of The Firebird. 1954. Graphite and gouache on paper. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019.

Design with birds and flowers. Study for textile design for House of Myrbor. 1925-1928. Gouache and graphite on embossed paper. State Tretyakov Gallery. Bequeathed by AK Larionova-Tomilina, Paris 1989. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019.

Linen. 1913. Oil on canvas. Tate. Presented by Eugène Mollo and the artist 1953. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019.

Natalia Goncharova. The exhibition Is at Tate Modern until September 8, 2019. Open daily 10-18 and until 22hrs on Fridays and Saturdays.