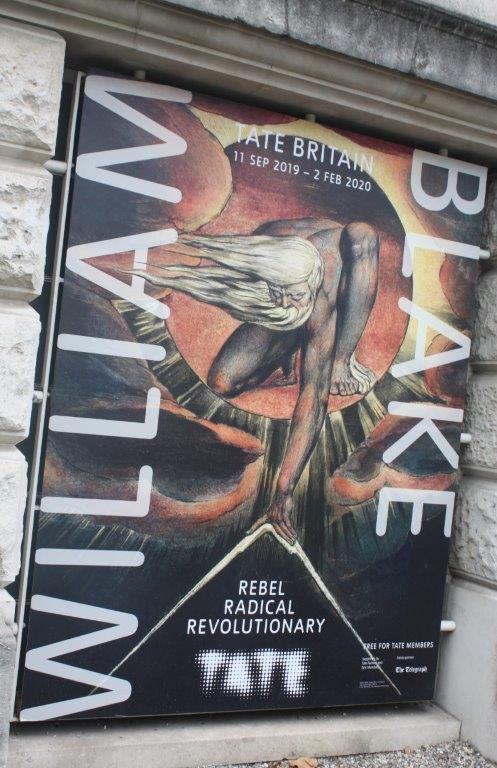

William Blake: visionary exhibition at Tate Britain

By James Brewer

William Blake aspired to be the Michelangelo of England. He was never to achieve that ambition: some of his patrons were wealthy, but insufficiently so to sponsor his grander projects, and since he was unable to accommodate to organised religion, he was unlikely to have won any commissions remotely as prestigious as painting the Sistine Chapel.

In some respects, he was like Michelangelo. He did prolifically write powerful poetry, and like his hero created muscular figures in dramatic postures. From the mid-19th century he came to be recognised as “a new kind of man” and in the current era as one of the greatest cultural figures of all time.

His hostility to empire, tyranny and slavery distanced him from the establishment of his time, which in any case viewed him as a minor figure. On all questions, he was unafraid to speak his mind – he dogmatically condemned the “blurring and blotting” of some of the most revered painters (he wrote of “the ignorances of Rubens, Rembrandt, Titian and Correggio”).

Today Blake (1757-1827) is considered a “Tyger burning bright,” to quote one of the most famous lines from his extensive poetry – poetry that expresses humanity and burning passion for his causes. He could even be heard as the originator of the protest song: lyricists including Bob Dylan, John Lennon, Van Morrison, Jimi Hendrix and Led Zeppelin have all had their Blakean moments.

Blake’s startling visual world, and especially his close relationship to London where he was born and resided most of his life, are absorbingly traced in a new exhibition at Tate Britain. From the outset, visitors are plunged into an earlier, uncertain age of anxiety.

His determined individualism, his “visions” and his technical brilliance (he devised a way to print text on the same page as image) are seen against the turmoil of European revolution and conflict between nations. What would he have made of the crosscurrents and sub-plots of Brexit and geopolitical clashes around the globe?

Pleasingly, the extensive Tate display underscores the vital contribution of Blake’s industrious wife Catherine to steadying and enhancing his up-and-down career. One would have loved to see a full-colour portrait of her, but unfortunately it seems that none exists. There is just a rather faint sketch of her from 1802. His devoted helpmeet was apparently ever on hand to print and clean sheets of paper and to colour them to delight Blake’s admirers.

Catherine was an accomplished printmaker in her own right but unacknowledged in the production of Blake’s engravings and illuminated books. The curators say that Catherine’s creative and practical influence is only just beginning to be fully appreciated.

Catherine Boucher (1762–1831) was the daughter of a poor market gardener from Battersea. The couple married in 1782 and they remained close until his death. Blake taught Catherine to write, and she played a huge part in his creative and commercial work, even finishing some of his drawings. Blake’s extraordinary vision depended on his partnership with Catherine, Tate says.

Among other achievements, she is thought to have been involved in Blake’s illustrations for Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress from 1824-27 and for the popular poem The Complaint; or Night Thoughts 1797, a copy of which is on show.

This is part of what is billed as the largest survey of work by Blake in the UK for nearly 20 years, with more than 300 remarkable and rarely seen works and which, says the gallery, “rediscovers Blake as a visual artist for the 21st century.”

There is a fascinating surprise at the very end of Tate’s presentation of the potent prints and the penetrating visions, and that is a stand-alone, richly coloured and greatly detailed piece given the title latterly of The Sea of Time and Space (Vision of the Circle of the Life of Man), executed in 1821 and which is in the National Trust Collections.

Blake used ink, watercolour and body colour on gesso ground paper to return to what has been identified as a Greek classical theme of a type which he had eschewed since his days as a student at the Royal Academy, when he had disdained the tutors who taught boringly by demanding sketches of plaster casts of ancient Greek and Roman figures, exemplified in the exhibition by one of the daughter of Niobe.

The Sea of Time and Space had been out of public view until 1949 – when it was reportedly found amid rubbish on top of a wardrobe in in a pantry when the National Trust acquired Arlington Court in North Devon, which is now its usual home. Blake had sold the picture to Col John Chichester in the 1820s.

A Londoner through and through, Blake was familiar with the sea only from living in a seaside cottage in Felpham, near Bognor Regis between 1800 and 1803.

Packed with figures, mortal and immortal, the painting has been interpreted by the leading Blake scholar Kathleen Raine, who died in 2003, as being inspired by a 1788 translation of the treatise by Porphyry of Tyre on Homer’s Cave of the Nymphs, to which Blake added details from the Odyssey by Homer (who was according to Plato, “the one who has taught Greece”) and other sources.

Tate’s label for this painting does not mention this seeming Greek theme. It says that the kneeling figure has been identified as divine inspiration and imagination. The title is a quotation from what was planned as Blake’s prophetic summation of his mythic universe, a manuscript entitled Vala begun in the late 1790s. Planned as nine books, or nights, it was reworked over 10 years, but he was never satisfied with it.

Kathleen Raine understood the painting as being of the point where, returned from the Trojan war, Odysseus has just landed in Ithaca, in the cove of Phorcys, close to the cave of the nymphs. Odysseus is silhouetted against the tempest-tossed sea which has so long held him captive. He gestures towards the waves with an attitude of yearning and mysticism. Behind him is Athene, symbol of divine wisdom, representing the natural, or scientific, order of classical thought.

The suggestion is that Blake turned to the Odyssey to represent in one picture the perpetual cycle of the soul reflected in the spirits of light and water.

Kathleen Raine says that the extent of Blake’s borrowing from Greek mythology has been obscured by him choosing his own names for his ‘mythological’ characters.

As in much of Blake, his figures represent specific values and ideas: the universal embodiment of a notion. Any painting may have multiple meanings, the curators remind their audience, and this is to be firmly kept in mind when standing before any of Blake’s productions.

Although he wanted to create huge works to be installed on and in churches and other monumental buildings, Blake was confined largely to the more modest scale of the printed page – not that this is a loss for posterity.

Blake envisioned vast frescos, symbolising public figures, that were never realised: these would be paintings 30 m high for display on public buildings. Tate has digitally enlarged and projected onto a gallery wall at the huge scale that Blake imagined The Spiritual Form of Nelson Guiding Leviathan c 1805-9 and The Spiritual Form of [prime minister William] Pitt Guiding Behemoth c 1805.

Nearby is a restaging of Blake’s ill-fated exhibition of 1809, an attempt to create a public reputation for himself as a painter worthy of great public schemes rather than a mere competent engraver. Tate has recreated the room in which he organised the show above his family’s hosiery shop near Golden Square in Soho.

The solo exhibition was a depressing turning point. In his advertisement for the show, Blake excoriated “the ignorances of Rubens, Rembrandt, Titian and Correggio” whose use of colouring he deplored. “Till we get rid of” those artists, “we never shall equal Rafael and Albert Durer, Michael Angelo, and Julio Romano [a 16th century mannerist],” he declared, boldly comparing his exhibition of “real Art” to that of the last four named.

Blake invented mythological-style characters in his poems and paintings to underpin his philosophical outlook, personifying concepts and ideas.

He scorned the commercialisation of art and questioned received ideas in society and science. In 1784 he began an unfinished satirical manuscript An Island in the Moon in which he developed his prophetic modes of expression.

In the colour print Newton 1795-c.1805, Blake portrays a young Isaac Newton, rather than the older figure usually portrayed. Newton is crouched naked on a rock covered with algae, apparently at the bottom of the sea. His attention is absorbed with a diagram which he draws with a compass. Blake was critical of what he saw as Newton’s crude scientific approach which made him oblivious to the glories of nature such as the colourful rocks behind him.

The image Pity is taken from Macbeth in which pity is likened to a naked new-born baby. Blake wrote: “”Cherish pity, lest you drive an angel from your door.” Here he draws on a fair complexion signifying moral purity.

From Jerusalem: The Emanation of The Giant Albion is Copy A, plate 28: chapter-heading for “Jerusalem. Chap. 2.”, an illustration dominated by a giant water lily with two figures inside embracing. In the background are lily leaves and water, and below, 27 lines of verse beginning “Every ornament of perfection…” The right margin is illustrated with shellfish.

Jerusalem is the last, longest and greatest in scope of the prophetic books and has been described as “visionary theatre.” The poem, which was produced between 1804 and 1820, is on 100 etched and illustrated plates, telling the story of the fall of Albion, as the embodiment of man, Britain or the entire western world.

Blake was inspired by the ideals of the French and American Revolutions, although disillusioned by their failure to replace monarchy with truly progressive societies. He was deeply opposed to slavery and at the forefront of the abolitionist movement, propounding racial and sexual equality. Several of his poems and paintings express a notion of universal humanity: “As all men are alike (tho’ infinitely various)”.

Recurring themes are the power of women, love and jealousy, emphasising the relationship between sensuality and spirituality. In 1793 in Visions of the Daughters of Albion, Blake condemned enforced chastity and marriage without love and defended the right of women to self-fulfilment.

As it did with its Van Gogh exhibition, Tate puts a great focus on London. With a century between them, both great artists were moved by the rumbustious environment of the metropolis.

London appears in Blake’s illuminated book Songs of Experience, his central achievement as a radical poet, as the scene of exploitation and injustice. Despite this, it was only in London that he could “carry on his visionary studies… see visions, dream dreams.’

Except for three years spent in a little thatched cottage by the Sussex seaside, William Blake dwelled in London his entire life. He was born in Soho, and nearly 70 years later, died in rooms (“a hole” although he believed that God had a beautiful mansion for him elsewhere) just off the Strand, on the first floor of 3 Fountain Court. This was a red brick house with a view on to the Thames, which he described as looking like “a bar of gold.” He and his wife had been there since 1821. The location is close to the site on which the Savoy Hotel was opened in 1889.

For 10 years from 1790, Blake lived in North Lambeth, at 13 Hercules Buildings, Hercules Road, the site of which is marked with a plaque. In railway tunnels at nearby Waterloo station, there is a series of 70 mosaics reproducing illustrations from The Songs of Innocence and Experience, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, and his prophetic books.

Blake made 12 sepia drawings to accompany the rough and unfinished manuscript of Tiriel, a narrative poem he wrote around 1789, although three drawings are lost. Considered the first of his prophetic books, Tiriel remained unpublished until 1874, when it appeared in William Michael Rossetti’s Poetical Works of William Blake.

Tiriel combines elements of Greek tragedy and Shakespeare and Gaelic stories. The narrative is that long ago, Har – a character who roughly corresponds to an aged Adam – and his wife, Heva, who corresponds to Eve – were overthrown by their children, and came to reside in the Vales of Har, where they gradually regressed to a childlike state to suppose that their guardian, Mnetha, was their mother.

In the pen and wash drawing Har and Heva Bathing, Mnetha looking on (held by the Syndics of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge) the couple are immersed in the waters of matter. The Vales of Har are represented as a place of purity and innocence.

The exhibition closes with The Ancient of Days 1827, an illustration for an edition of Europe: A Prophecy, completed only days before the artist’s death. Its cover was coloured by Catherine.

The first of 17 plates for Europe is called, although not by Blake, The Ancient of Days. It shows a naked, bearded man, probably the character referred to by Blake as Urizen, wielding a huge pair of compasses to delineate the creation of the world.

Europe may have been intended as a tribute to the French Revolution and the beginning of a universal liberation of mankind… or to the perceived limitations of such revolutions.

The master’s poems are a subsidiary theme of the exhibition, but visitors will be inspired to turn to the voluminous works. There is a particularly touching example cited: Blake’s artist friend John Flaxman to please his wife Ann commissioned from Blake a set of watercolour illustrations of the poems of Thomas Gray. For 10 guineas Blake produced 116 watercolours and one poem of his own, inscribed on a wall of one gallery:

“A little flower grew in a lonely Vale/ Its form was lovely but its colours pale/ One standing in the Porches of the Sun/ When his Meridian Glories were begun/ Leaped from the steps of fire & on the grass/ Alighted where this little flower was/ With hands divine he moved the gentle sod/ And took the Flower up in its native Clod/ Then planting it upon a Mountains brow/ ‘Tis your own fault if you don’t flourish now.’”

The grand Tate exhibition should encourage everyone to look philosophically beyond the superficial, or as Blake said: “To see a world in a grain of sand/ And a heaven in a wild flower,/ Hold infinity in the palm of your hand,/ And eternity in an hour.”

William Blake at Tate Britain is meticulously curated by Martin Myrone, senior curator of pre-1800 British Art, and Amy Concannon, curator of British Art 1790-1850.

Captions in details:

The Sea of Time and Space, 1821. Ink, watercolour and body colour or gesso green paper. National Trust Collections, Arlington Court (the Chichester Collection)

Har and Heva Bathing, Mnetha looking on, c 1819. Pen and wash on paper. The Syndics of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

Portrait of William Blake, 1802. Pencil with black, white, and grey washes. Collection Robert N Essick.

Catherine Blake drawn by William in 1805. Graphite on paper. Tate. Bequeathed by Miss Alice GE Carthew, 1940. Tate.

Newton, 1795-c 1805. Colour print, ink and watercolour on paper. Tate.

Pity c 1795. Colour print, ink and watercolour on paper. Tate

Jerusalem, plate 28, proof impression, top design, 1820. Relief etching with pen and black ink and watercolour on medium, smooth wove paper. Yale Center for British Art (New Haven, USA).

Europe. Plate i: frontispiece, known as The Ancient of Days, 1827 (?). Etching with ink and watercolour on paper. © The Whitworth, University of Manchester.

The exhibition at Tate Britain runs until February 2, 2020.