Royal Academy’s homage to Léon Spilliaert, Ostend artist fascinated by the North Sea

By James Brewer

Looking out to the North Sea from his home in Ostend was endlessly fascinating for the artist Léon Spilliaert. From 1908 he rented an attic studio close to the fishing port of the Belgian town which meant he could contemplate and represent the moods of the watery vista by day and by sleepless night – he was an insomniac.

In his austerely poetic interpretations, he returned time and again to the marine subjects at his doorstep: the mystery of the tides and their interplay with the sky and moonlight, the dykes and quays, the perilous occupation of commercial fishing and its anxious womenfolk, and the expansive beach with its promenade; while in the early part of his life he dwelt on his own morose persona in self-portrait. His style is spare and terse, anchored in his emotions and environs.

At his easel, the principle was less is more, but long overdue recognition on this side of the great sea of his talent is being bestowed by the Royal Academy of Arts which has unveiled the first major exhibition in the UK tracing his career.

Léon Spilliaert (1881–1946) lived through an era of huge ferment in the visual arts, but eschewed artistic schools as he pursued his individual path.

Royal Academy secretary and chief executive Axel Rüger said that the artist was little known outside Belgium, “but I hope that many visitors will turn into dedicated followers of Léon Spilliaert,” whose art was informed by the environment of Ostend in which he grew up. This was very introspective, rather intense work.

Dr Adrian Locke, joint curator of the exhibition, said that when he first got to know of Spilliaert he was “blown away by the range of works I saw, particularly the seascapes.” He added: “At times, I think, he was a very troubled artist.”

With 80 works from public and private collections in Belgium, France, the UK and the US, the exhibition offers a welcome window on the intriguing artist who despite his low profile influenced the surrealists and other better-known personalities with whom he was contemporaneous.

Spilliaert in his way was as important as many of them. He was born in the same year as Pablo Picasso, but the two were of altogether different temperament, one introvert and one extrovert, as can be seen in their output. Both were revolutionary in their visual approaches. Unlike the cosmopolitan Picasso, Spilliaert was always a man of his birthplace, principally of subdued out-of-season Ostend, which was a bustling and fashionable resort in summer.

By means of atmospheric images of his hometown and its intimacy with the sea – in visions that were dreams short of nightmares – Spilliaert experimented with unusual perspectives and bold geometries, investigation which was to become the hallmark of a school of Russian and other European artists.

The RA charts compellingly the course of this self-taught artist, who spurned oil paint as he turned out 4,500 works preferring combinations of Indian ink wash, crayon, watercolour, gouache, pastel, chalk, pencil and pen. They are usually on paper which seems to bring them closer to the viewer.

As a young man, his insomnia and a chronic stomach ailment led him to pace alone the deserted promenade and streets of his city in the dead of night, when he observed the diffused effects of street lighting and the reflections of rain.

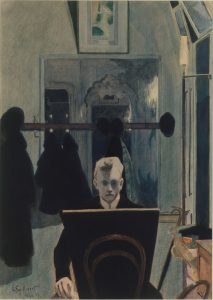

His early works including self-portraits are close to spectral, imbued with mystery and melancholy which has led him to be aligned by critics with other anguished Nordic artists such as Norway’s Edvard Munch, Denmark’s Vilhelm Hammershøi and Finland’s Helene Schjerfbeck. That is perhaps overstating the comparisons – the work is earnest, but despite first appearance, not always sombre.

His initial sources of inspiration were the flasks in his father’s perfumery shop (which supplied the court of Leopold II), and examples of such illustrations are on display. He grew up appreciating the writings of Edgar Allan Poe, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Schopenhauer, and a turning point came in 1902, when he was commissioned at the age of 21 by a leading Brussels publisher, Edmond Deman, to illustrate books.

Among the commissions were a set of 10 lithographs for the first collection of poems, Serres Chaudes by Maurice Maeterlinck, the only Belgian to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature; and scenes for the poet Emile Verhaeren, with whom he formed a close friendship. Verhaeren introduced Spilliaert to important figures in art and literature, including the great Vienna-born novelist and playwright Stefan Zweig and the Belgian dramatist Fernand Crommelynck.

Between 1907 and 1913 Spilliaert struck out with a new aesthetic of expressionism based on symbolism, a term which had been coined just over 20 years earlier by the French critic Jean Moréas to describe the poetry of Stéphane Mallarmé and Paul Verlaine. Spilliaert’s imaginary worlds were less extreme than those of his fellow Belgians Fernand Khnopff and Jean Delville; the symbolist flame was also being nurtured in France by Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon and Paul Gauguin and in Britain by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, George Frederic Watts and Aubrey Beardsley.

Devoid of clutter, Spilliaert’s depictions invest geometric landscapes with shades of inky black to grey to create a sense of emptiness and stillness.

His nocturnal strolls led to harbour scenes such as Fisherman’s Wife from 1912 in which women wait for the boats to return. He was friendly with another Ostender, James Ensor (1860–1949) who would reap greater fame. Ensor, whose canvases are bolder and brighter, called him “the virtuoso of the sea, the disciple of Verlaine, [who] poeticises rusted waters, dead-leaves, faded flowers, decaying bouquets, severe branches… “

Spilliaert’s subtle hues raise questions of meaning: the face of the girl in A Gust of Wind (1904), has been compared to Munch’s 1893 The Scream, but after all is an impenetrable enigma.

In 1904 during a brief stay in Paris Spilliaert had become familiar with the work of Munch and Toulouse-Lautrec, while drawings from Picasso’s blue period were shown besides his dark wash-drawings at a gallery there.

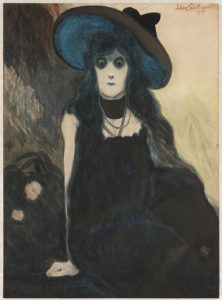

His experience of France may have shaped the mode of the powerful portrait La Buveuse d’absinthe (The Absinth Drinker) in 1907. This is a rare example of a full-face view, but it was a mechanism to convey her stare in her dissolute state. This important work was acquired by the King Baudouin Foundation Heritage Fund at a Sotheby’s Paris sale and entrusted to the Fine Arts Museum of Ghent.

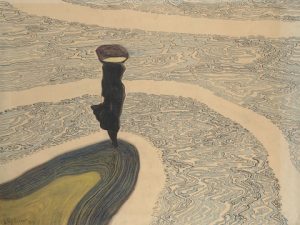

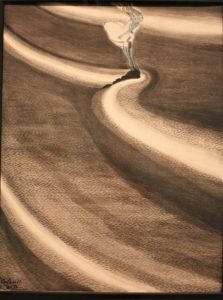

Stylistically La Buveuse d’absinthe fits in with Spilliaert’s series of 15 self-portraits, saturated with solitude and disconsolance. It is typical of his ability to suggest a whole story within deceptively simple but bracing lines such as the undulating breakers in Fillettes devant la vague (Girls in the Waves) from 1908. Against the force of the swirling billows two delicate girls cling together anxiously on a rock just inside the picture but still command all the attention. Of similar impact and sensitivity is Woman at the Shoreline made in 1910.

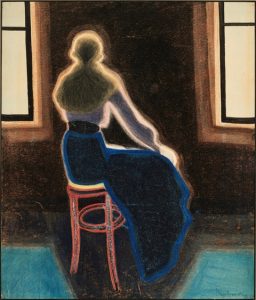

He was captivated for many years by the maritime environment espied from his home. In works including Young Woman on a Stool, 1909 (lent by the Hearn Family Trust) solitary women wait for their husbands to return with their catch from the sea.

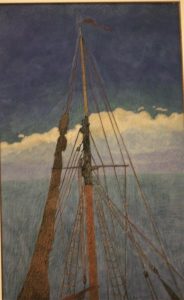

Through his window he could see the upper parts of ships, and among other views, in 1914, he accomplished The Mast, in Indian ink, gouache, casein, watercolour and coloured chalk on cardboard.

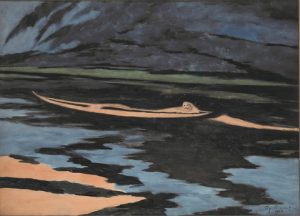

More gloomily, The Shipwrecked Man depicts what could be the shards of a small boat, or a sandbank with the hint of a lone survivor.

Fleeing Ostend in 1917 to escape the German occupation, Spilliaert and his new wife Rachel Vergison made for Geneva, where they planned to join a pacifist movement, but hard-up and with a baby girl just born, they got no further than Brussels. Their daughter, Madeleine, would later train in the capital as a concert pianist.

Happiness in his family life transformed his output. As he moved between Ostend and Brussels he produced contemplative, tranquil seascapes in evening light or sketches of beech trees in the Forêt de Soignes, where he walked regularly, near the capital.

Earlier, Spilliaert had been excited by a change of topic: a commission to illustrate one of the first airships in the country. He was asked by a good friend, Robert Goldschmidt (1877–1935), a successful scientist and aviation enthusiast, to record the progress of his second airship Belgique II being readied in its hangar at Oudergem to the southwest of Brussels. Spilliaert, who witnessed the maiden flight of the 65 m long zeppelin in April 2010, produced 15 strongly-lined pictures of the dirigible in all its bulky splendour, three of which are on show at the RA.

Spilliaert’s Ostend family home was destroyed by bombing in World War II. A new gallery, Het Spilliaert Hus, dedicated to the artist has opened on the promenade in the Thermae Palace, a building which he had depicted. Dr Anne Adriaens-Pannier, director of that gallery, is the leading expert on Spilliaert and has had close contact with the artist’s family including his grandchildren.

The exhibition originates at the Royal Academy and will travel to the collaborating Musée d‘Orsay, Paris. It is curated by Dr Adriaens-Pannier, who is honorary curator of the Musées royaux des BeauxArts de Belgique, Brussels, and Dr Locke, senior curator at the Royal Academy.

Picture captions in detail:

Woman at the Shoreline. 1910. Indian ink, coloured pencil and pastel on paper. Private collection. Photo: © Cedric Verhelst.

Young Woman on a Stool, 1909. Indian ink, pen, coloured pencil, coloured chalk and gouache on paper. The Hearn Family Trust.

A Gust of Wind, 1904. Indian ink wash, brush, watercolour and gouache on paper. Mu.ZEE © www.lukasweb.be – Art in Flanders vzw. Photo: Hugo Maertens.

The Mast. 1914. Indian ink, gouache, casein, watercolour and coloured chalk on cardboard. Axel Roche de Bellefroid.

Fillettes devant la vague (Girls in the Waves). 1908. Indian ink wash, pen and pencil on paper. Private Collection.

The Shipwrecked Man. 1926. Watercolour, gouache, Indian ink and pen on paper. Private collection. Photo: Luc Schrobiltgen.

The Absinthe Drinker, 1907. Indian ink, gouache, watercolour and coloured chalk on paper, Collection King Baudouin Foundation, entrusted to the Fine Arts Museum of Ghent, Belgium, © Studio Philippe de Formanoir.

The airship emerging from the hangar. 1920. Indian ink wash, brush, gouache and pastel on paper. Musées royaux des BeauxArts de Belgique, Brussels.

Self-portrait, 1907. Gouache, watercolour and coloured pencil on paper. Metropolitan Museum of Art © 2019. Image copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence.

Léon Spilliaert exhibition, supported by the Government of Flanders, is at the Royal Academy, in the Jillian and Arthur M Sackler wing, until May 25, 2020.