Jean, Lady Hamilton: A Soldier’s Wife – biographer Celia Lee on decades of revelatory diaries

By James Brewer

For the young couple Jean and Ian Hamilton, the first society dinner party they hosted in the Indian hill town of Simla was a disaster: one embarrassment after another. The house steward filled the wine glasses with whisky instead of sherry, and the cook put so much Bombay Duck (a dried fish preparation) in the curry that it set off an overpowering smell.

After dinner, Ian was adding kindling to the fire when his wife lent over to warm her hands. Her hair brushed against his face, and lovingly he caught a curl between his lips. The curl came away – it was a false one mixed in with her natural tresses, as was the fashion. Jean was mortified by the mishaps, but the guests found them all part of a jolly good evening.

That was the way that Ian recalled an episode in the 1880s early in their married life, but Jean was soon committing to paper extensive details of their life together. From minor domesticities to intimacies and comments on affairs of state, Jean, Lady Hamilton became a life-long diarist.

Her husband General Sir Ian Hamilton was celebrated for his Boer War exploits but led the ill-fated attack at Gallipoli during the First World War. The couple were close friends of Winston and Clementine Churchill, who figure frequently in Jean’s telling.

Her deeply moving story is told, through copious extracts from her diaries and contemporary context and memoirs, in Jean, Lady Hamilton, A Soldier’s Wife which the accomplished biographer and military historian Celia Lee has updated for a new edition. The diaries remained forgotten in the Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives at King’s College, London, for 50 years.

The chronicles embrace the Victorian and Edwardian eras of global conflict and social upheaval, largely from the perspectives of the aristocracy and of military chiefs.

The pages throw light on some key personal and political aspects of Churchill’s life, on behind-the-scenes manoeuvring of would-be influencers of the day, and of Jean’s circle of friends and society ladies such as the irrepressible chatterbox Lady Cunard; but above all on the caring and selfless character of the more restrained (at least in public – she lobbied vigorously in the highest circles on behalf of her husband’s advancement) Lady Jean.

Jean met Major Ian Hamilton (born to an army colonel and his wife in 1853 in Corfu) while on holiday in India and they were married in Calcutta. She was the daughter of the jute and tea millionaire Sir John Muir and possessed of beauty and a handsome annuity, and her groom was just about penniless.

In true Jane Austen style, says Celia Lee, Sir John was a gentleman and Jean born in June 1861 was a gentleman’s daughter. Sir John and his wife Margaret, Lady Muir, presided at Deanston House, a mansion by the River Teith in Perthshire, over a family of 10 children.

Jean used her share of the fortune built up by her father to finance her husband’s career in the army. She emerges as a woman doing a great deal behind the scenes, says Celia Lee, for which she received little or no recognition. She worked tirelessly for soldiers both at home and in packing food parcels to send to hospital ships during the Dardanelles campaign.

An active member of the Red Cross, she threw parties for wounded soldiers every Thursday during the war and supervised the despatch of supplies and comforts for the Gallipoli troops. The clothing, soap, cigarettes, sewing kits, apples, bandages, bedding and so on was shipped to Gallipoli, to the base hospitals at Mudros on the island of Lemnos in the Aegean, and to Alexandria and Malta.

Before her marriage, Jean had been in love with Lord Alwyne Compton, son of the 4th marquis of Northampton, who travelled across India to see her in Jaipur only to find that she was away in Bombay at the time, and was devastated when he became engaged to Mary, daughter of the millionaire Robert Vyner. Jean met Ian Hamilton at a time when she was about to become engaged to Prince Louis Esterhazy, who was related to the royal families of Europe, but was put off by the way the prince kissed her. She thus sacrificed the chance of a royal crown at the court of Vienna but escaped further disgusting kisses.

Romance was ever in the air in the late 19th century in India for army officers, and Hamilton and Churchill were no exceptions. In 1896 Churchill at the age of 21 while serving in the 4th Hussars was smitten by Pamela Plowden, whom he met during a polo tournament and wrote to his mother of “the most beautiful girl I have ever seen.” She declined his proposal of marriage, but the two remained friends for 60 years. She later became Countess of Lytton.

Churchill admired Hamilton and when in 1900 he published his Boer War dispatches based on his reports for a London newspaper it was under the title Ian Hamilton’s March.

For the first 10 years of their marriage the couple lived in India. In 1898, Ian received an offer of a job at Hythe, Kent. Jean did not like the house at Hythe until she had the interior restructured so that she could see the sea and ships from her bedroom window.

Jean confides to her diaries how lonely the life of a soldier’s wife can be. She quotes from a letter written in 1823 by a mistress of Lord Byron, Lady Caroline Lamb, who complained: “I am in an unsought-for sea, without compass to guide, or even acknowledge whither I am destined.” Jean comments: “Well I do know the lonely terror of that uncharted sea.”

Offsetting the loneliness, she progressed Ian’s career by countless lunches, dinners and meetings with leading military and government figures.

Ian completed two spells of duty in the Boer War (1899-1902) and in the later stages he was chief of staff to Lord Kitchener. In 1904 he set off to Japan in search of a new role and became an official observer of the Russo-Japanese war. Back in England he took up the southern army command at Salisbury in 1905, and in 1909 returned to London for the War Office.

In 1910 the Mediterranean command took him to Malta where, for the first time since India, Jean lived with him overseas, at San Antonio Palace. In 1914 they returned to London Ian having become commander in chief of Home Forces. They bought No 1 Hyde Park Gardens, where they were to reside for many years, and in 1918 rented and then bought as a country home Lullenden Manor in Sussex, from Churchill who could no longer afford to live there.

The London house had just been decorated when war broke out. Ian went to Gallipoli as commander in chief of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force from March to October 1915, a time anxiously followed from afar by Jean. The debacle there ended his military career and almost ended that of Churchill who had to quit as First Lord of the Admiralty. It has since been suggested that the Allied campaign came close to succeeding and Jean’s diary entries back up the assertion that the humiliation can be blamed largely on the failure of Lord Kitchener as secretary for war to sanction fresh troops and ammunition as the Turks poured in reinforcements and fired up to 2,000 shells an hour.

Jean comments extensively on the infighting at Cabinet level over the Gallipoli campaign. Lloyd George wanted to get the operation shut down and the resources transferred to Salonica, as Thessaloniki was referred to, despite which Ian “held on bravely” in Jean’s diary words. The pivot to northern Greece was a belated effort to help Serbia deter Bulgaria from joining the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary. The Allies also hoped to persuade a politically divided Greece to join the Allies.

Battalions would be sent from the peninsula to Lemnos for rest and reorganisation before embarking for the Greek mainland. In October 1915, the first British troops landed at the Greek port from Gallipoli and France, although War Office support in this case too turned out to be weak for the next three years.

Jean believed Churchill had blundered in failing to order concerted action when the navy first went to bombard the Dardanelles, but otherwise was supportive of him as Ian’s ally within the Cabinet.

Hamilton for a long time like Churchill had to suffer public opprobrium over the failed Gallipoli action – later his reputation was restored, but he was never again employed on active service.

Dressed in the finest fashions, Jean glided through London’s grand dinner parties, balls, and public functions, and enjoyed holidays in France, Italy, and Monte Carlo. She floated in a sea of society hostesses, including Lady Randolph Church, mother of Winston, whom Jean says she adored; Clementine, Winston’s wife; fellow Scot Alice Keppel, the mistress of Edward Prince of Wales (and great-grandmother of Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall); and Lady Cunard, a gossipy and scheming American heiress.

She was widely read and loved poetry: several of her poems were published including her wartime verses about Gallipoli. A gifted artist, she produced fine pastels, and the painters John Singer Sargent, Walter Sickert and Charles Furse were among her friends. At a holiday villa in Italy, Sickert (by whom she was fascinated) platonically carried her upstairs to her room – she was asthmatic – when a servant was not there to perform the task.

Winston Churchill with Clementine were like family in the Hamilton home, where he used to practise his speeches, and painted alongside Jean to whom he sold his first painting. A remarkable episode shows how close they were. With the Churchills in 1918 in genteel poverty, Clementine could not afford the £25 fee to enter a nursing home to give birth to her fourth child. In private conversation after a dinner party, Clementine asked Jean if she would adopt the as yet unborn baby (Jean writes in her diary “of course I said I would.”)

A couple of weeks later though, Jean received a letter from the matron of an orphans’ home offering her a baby girl who was to be born out of wedlock to a lady’s maid. Jean wanted to call the girl Rosaleen as the father was said to be of Irish gentry, although she had already been named Phyllis Ursula James (and came to be known by her pet name of Fodie, a child-like corruption of the sound of Rosaleen).

Jean’s longing to have children had been unfulfilled, taking second place to Ian’s duty on the battlefield and other postings overseas. The painful disappointment was offset by fostering Fodie and an orphan boy, Harold Knight (Harry).

As to the Churchill baby, who was named Marigold, her life ended in tragedy just before her third birthday, a victim of the post-war ‘flu pandemic. The story of her fate lay buried until Jean Hamilton’s diaries were unearthed in the 1990s. Only in 2001 was Marigold’s grave confirmed in Kensal Green cemetery, north London. Clementine’s daughter Mary, the Lady Soames (who died at the age of 91 in 2014) supported Celia Lee in publishing the story of her short-lived older sister.

Of her mother’s offer to give away the child, Lady Soames in an interview with the author explained: “My mother was exhausted during this period of her life. In common with many people she had undertaken a great deal of war work. She may have thought at that time that another child was too much of a burden to cope with.” The funeral was a private, family affair.

Lady Soames told the author she never knew her mother offered to give the baby away to Lady Hamilton, so Clementine took that secret with her to her grave. Winston never knew either as he was with the men in the smoking room at the Hamilton home house when the conversation took place.

Among the aristocrats to pop up frequently in the book is Lady Maud (née Burke) who had married Sir Bache Cunard in 1895. He was grandson of the founder of the Cunard shipping line, established in 1840 by Canadian-born Samuel Cunard as the British and North American Royal Mail Steam Packet Co. It became the first company to operate scheduled steamships across the Atlantic and is still running a service between Southampton and New York. In recent times the Cunard brand has lived on within the Carnival Corp group.

Lady Cunard gave herself the colourful nickname of Emerald and had long relationships with the novelist George Moore and the conductor Thomas Beecham. The American-born heiress graced Jean’s table and countless other parties, dining sumptuously.

Maud’s conversation at times “reached the height of folly,” as Jean once put it, and she quotes another friend as saying she was “yapping like a mad poodle.” Despite that, Jean admired Lady Cunard for her “vitality courage and determination, and they have gained her what she set out to in.” Lloyd George had a stronger opinion. He considered Lady Cunard “a most dangerous woman”, because although she was not greatly interested in politics, at her dinner table she beguiled senior politicians into indiscreet statements.

Lady Cunard reached the top of the social tree, moving in the same circle as Edward Prince of Wales and his mistress the American divorcee Mrs Wallis Simpson. She was a supporter of Mrs Simpson during the abdication crisis of 1936, hoping in vain for court preferment. The heir to the throne’s name had earlier been linked romantically with Thelma Lady Furness, wife of the shipping magnate Lord Furness.

The Cunard daughter Nancy earned a contrary claim to fame than her mother: she devoted much of her life to fighting racism and fascism., while becoming a muse to some of the 20th century’s most distinguished writers and artists.

Jean relied heavily on her servants and even had to have her bedside clock set by them to mark the changing of the seasons. Of them all, she was closest to the one she knew by her surname, McAdie. Mrs Helen McAdie was Jean’s faithful maid for many years and died of a heart attack while in service.

Jean predeceased her husband. She died at Blair Drummond Castle, the Scottish home of her brother Alexander Kay Muir and his wife Nadejda (Nadia) the brilliantly intellectual daughter of a Bulgarian diplomat, Dimitri Stancioff. Jean’s dying days were in a suite where King Boris and Queen Giovanna of Bulgaria once stayed.

She died unaware that her young son Harry was killed in action in the Libyan desert. Fodie, having been sent to be educated at a private school was trapped in war-torn Europe and never returned home. Fodie’s daughter Nadejda James Muñoz who lives in Spain never met her grandparents.

In an interview by email for this article, Mrs Muñoz said that Rosaleen (Fodie) seldom talked of her adoptive mother “but in fact, was more attached to General Hamilton. Mother was very introvert, and not given to talk about her childhood in general.”

Mrs Muñoz said: “It is wonderful that Celia Lee has brought Lady Hamilton back to life – and in such a marvellous way. I hope that people will not only enjoy reading Celia´s great biography, but also appreciate the goings-on of those times described in the book, and the part Lady Hamilton contributed to it all.”

She said of the account of Lady Hamilton: “I was impressed to discover a very feeling and passionate woman, totally dedicated to her husband. A love affair which lasted until the end of her life. To think that she chose Major Ian Hamilton over Prince Louis Esterhazy.

“I regret very much not having had the opportunity of meeting such a great lady. Admirable was her stamina and her abnegation. She was surely a pillar to many in her society.

“I could read between the lines that Lady Hamilton was totally unselfish and cared a lot about those near to her and those in need of help. The end of her life is very melancholic, I found. She suffered a lot, and not only physically. Her illusion had been to be surrounded by her two children when old. But it was not meant to be. In view of her frustration, she disinherited my mother during the last days of her life. Harry had already fallen in the North of Africa at the time. And mother was stranded in Berlin during the war, with no way of leaving there.”

This book is a reminder that the society of those days was not all as frivolous as many may believe, said Mrs Muñoz.

Mrs Muñoz said that her mother “lived a rather spartan life. Her main interest was in literature. She wrote books, poetry and plays, mostly in German. Some of her work has been published. She was under the belief that she was of Irish origin. In view of this belief mother went to live in Ireland, taught herself Irish (even wrote a book in Irish), opened a school in Galway, and was very happy there. The last years of her life were spent in Vienna where my brother lives. She died in 2013, just short of her 95th birthday.”

Celia Lee is a member of the British Commission for Military History and joint chair of the Women in War group, London. She is author of Winston & Jack the Churchill Brothers; The Churchills A Family Portrait, HRH The Duke of Kent A Life of Service; and joint editor of and contributor to Women in War From Home Front to Front Line.

Picture captions in detail:

Jean, Lady Hamilton, 1900. Copyright Mr Ian Hamilton.

General Sir Ian Hamilton and Winston Churchill at a reunion of the Royal Naval Division, Crystal Palace, London, 1938. (by kind permission of Mr Ian Hamilton great nephew of the general).

A party for soldiers at the Hamilton’s house, No.1 Hyde Park Gardens. Copyright Mr Ian Hamilton.

Lord Alwyne Compton. Copyright Lord Northampton

Mrs Helen McAdie, Jean’s maid of many years.

Phyllis Ursula James (Rosaleen/Fodie) as bridesmaid at the wedding of Sir Alexander Kay Muir and Miss Nadejda Stancioff (by kind permission of Mrs Nadejda James Muñoz).

Harold (Harry) Knight, Jean Hamilton’s adopted son, aged 2 years, (by kind permission of Mr Ian Hamilton).

Wedding of Mr and Mrs Hamilton, Spanish Town, Jamaica, 1987. Left to right: Miss Helen Hamilton; Mr William Hamilton (best man); Mrs Barbara Kaczmarowska Hamilton (bride); Mr Ian Hamilton (groom); Miss Laura Hamilton (bridesmaid); Mrs Sarah Hamilton and her husband Mr Alexander Hamilton.

Donald Trump in pre-presidential days some years ago with sons of today’s Hamilton family, with whom he is friends; and as is well known, Mr Trump is a great admirer of Churchill.

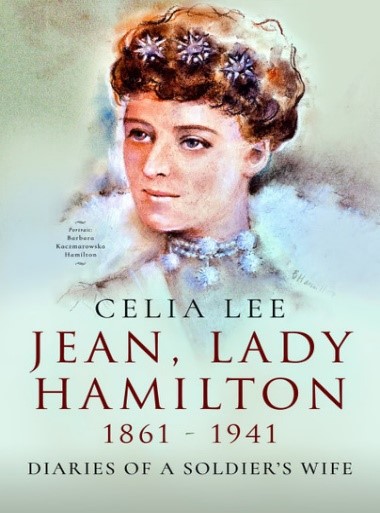

Jean, Lady Hamilton (1861 – 1941), Diaries of a Soldier’s Wife. By Celia Lee. ISBN: 9781526786586. Updated edition published in October 2020 by Pen & Sword. Barbara Kaczmarowska Hamilton, a much-lauded artist who is married to Ian Hamilton, great-nephew of General Sir Ian Hamilton, painted a new portrait for the cover.