Whistler’s Woman in White: Joanna Hiffernan. Royal Academy highlights the model who was so much more than a muse

By James Brewer

All who knew her were enthralled by her Pre-Raphaelite beauty, with enchanting pale blue eyes and tumbling copper-gold hair. Immortalised as a model by the American artist James McNeill Whistler who spent many years in London, Joanna Hiffernan was much more than a muse. The woman whom Whistler enlisted for his renowned The White Girl, for a famed tavern balcony scene with a view out to the bustle of Thames shipping, and for illustrations for his short stories and serialised novels was a loyal companion who outspokenly defended him against “stupid” art critics.

She was a capable business manager and housekeeper, an intelligent conversationalist who loved Irish songs, cared for Whistler’s child from another woman, and was a sometime painter herself. With such qualities and her adventurous dress sense, she entranced a friend of Whistler, Gustave Courbet, who painted memorable portraits of her and with whom she was said to have had an affair in Paris.

Her eventful life is central to Whistler’s Woman in White: Joanna Hiffernan which has opened at London’s Royal Academy. It is the first exhibition to examine how the Irish-born Hiffernan (1839?–1886) helped establish the reputation of Whistler (1834-1903) as one of the most influential artists of his era.

Without overloading details of the pair’s personal story, the Academy explores their professional and personal relationship over more than 20 years and demonstrates how the best-known artwork resulting from their collaboration resonated with artists well into the 20th century. Consisting of over 70 works, the exhibition includes nearly all of Whistler’s depictions of Hiffernan, and some by Courbet.

The highlight is the artistic spark between Whistler and Hiffernan during their liaison from 1860–66 that resulted in the three Symphony in White paintings that have been rarely shown together. These are the life-size Symphony in White, No I, also known as The White Girl, from 1862 (National Gallery of Art, Washington); Symphony in White, No II: The Little White Girl, from 1864 (Tate) and Symphony in White, No III, from 1865-67 (Barber Institute of Fine Arts, Birmingham University).

Whistler was in Paris when he worked intensively on the first Symphony during the winter of 1861–1862, in time for it to be submitted to the 1862 Royal Academy exhibition in London. Hopes that this would triumphantly fire up his career were dashed when he found the canvas stacked amid the rejects. The nearby commercial Morgan’s Gallery did accept it in 1863, when Whistler wrote of his model: “She looks grandly in her frame and creates an excitement in the artistic world here… In the catalogue of this exhibition, it is marked ‘Rejected at the Academy.’ What do you say to that? Isn’t that the way to fight ’em!”

The press declared the work “bizarre” and “incomplete”, and more insults were to follow. Rejected by the 1863 Paris Salon, it was chosen for the Salon des Refusés, a protest exhibition organised on the initiative of Napoleon III by Courbet, and which gathered paintings deemed to offend conventional taste – in the same room was Édouard Manet’s much more ‘outrageous’ Déjeuner sur L’Herbe.

What the establishment patrons resented was the depiction of a ‘lower-class’ Irish immigrant girl in the manner and at a scale usually reserved for portraits of wealthy and powerful subjects. Whistler said: “My painting simply represents a girl dressed in white standing in front of a white curtain,” but was later to claim that the painting was an aesthetic experience analogous to music, a “symphony in white.” By changing the title of the large work to Symphony in White: No 1 Whistler sought to focus attention on its thick white pigments and tonal contrasts. His foray into musical symbolism continued in the succeeding decade, when he re-titled various works as Nocturne, Arrangement, Harmony, and Symphony.

In the much-discussed picture, Joanna, wearing a white cambric housedress, stands on a rug of wolfskin or bearskin in front of a white curtain. Perhaps signifying a lack of innocence, her red hair is unrestrained, falling to her shoulders, and from her hands a lily drifts towards the floor.

Joanna was annoyed by the mixed reception the painting received. “Some stupid painters don’t understand it at all,” she wrote, “while Millais for instance thinks it splendid, more like Titian and those old swells than anything he has seen – but Jim says that for all that, the old duffers may refuse it altogether.”

Symphony in White No II was hung at the Royal Academy in 1865 as The Little White Girl. It shows a young woman, dressed in a white muslin morning dress, leaning against a mantelpiece in Whistler’s house in Chelsea and gazing into a mirror. Her face with its wistful expression is reflected in the mirror and silhouetted against a seascape, reinforcing a theme of reverie and regret. She holds a fan by the Japanese master of the woodblock print Utagawa Hiroshige, an idol of Whistler, who in the composition may have intended to evoke Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus (held at the National Gallery, London). Whistler was fascinated by Japanese art and culture. The fan, the red pot and blue and white vase on the mantelpiece, and a spray of pink azalea give the picture a Japanese feel, while providing brilliant colour against a background of black, white and cream. Items from Whistler’s porcelain collection and four woodblock prints including Hiroshige’s The Banks of the Sumida River, from 1857 (Victoria and Albert Museum) underline the point.

This “second symphony” inspired the pre-Raphaelite poet Algernon Charles Swinburne to compose Before the Mirror, a ballad “suggested to me by the picture, where I found at once the metaphor of the rose and the notion of sad and glad mystery in the face languidly contemplative of its own phantom.” It was intended to complement, rather than explain the picture. Whistler was delighted, the curators say, and had the poem printed on gold paper and pasted onto the frame. Swinburne wrote:

White rose in red-rose garden/ Is not so white; … My hand, a fallen rose/ Lies snow-white on white snows,/ and takes no care. … Come snow, come wind or thunder/ High up in air, / I watch my face and wonder/ At my bright hair.

Glad, but not flushed with gladness,/ Since joys go by;/ Sad, but not bent with sadness,/ Since sorrows die;/ Deep in the gleaming glass/ She sees all past things pass,/ And all sweet life that was lie down and lie.

In Symphony in White, No. III, the last of Whistler’s canvases for which Joanna modelled, she reclines in a white dress on a sofa draped in white, with a second woman in white – a professional model, Emelie Jones, seated on the floor by her feet. Although Whistler again chose the term ‘Symphony’ to emphasise to visitors to the Royal Academy’s exhibition in 1867 that it was purely a study in colour, they might have been tempted to draw other, sexual, conclusions.

Joanna Hiffernan, possibly studying art and modelling, had met Whistler in 1860 after he arrived in London from Paris. Rejecting the opportunity of staying with his half-sister in Sloane St, Whistler took lodgings in the east of the city at Wapping, where the couple lived for several months. There, influenced by the poet and critic Charles Baudelaire’s injunction to pursue subjects from modern life and indulge in the milieu of working people, Whistler dwelled among the dockers, watermen and lightermen of the area, frequenting the pubs where they ate and drank. Charles Dickens, Whistler’s contemporary shared this fascination with the riverside habitats of the poor.

Whistler worked on the first version of his painting Wapping (completed 1864; National Gallery of Art, Washington DC), a waterfront scene for which Hiffernan modelled the figure of a woman seated at a terrace table at the Angel Inn, a pub they frequented, with two men, with the background of the waterway crowded with the ubiquitous merchant sail craft of the day.

The pre-Raphaelite Dante Gabriel Rossetti called Wapping “the noblest of all the pictures he has done.” Judging by a sketch in pencil on paper in a notebook in Whistler’s leather-covered passport – shown in the exhibition alongside the oil painting – Whistler’s intention was to paint a couple on the pub balcony but changed this to three seated figures including Whistler and the French artist Alphonse Legros. The pose and dress of the woman modelled by Hiffernan (including a low neckline that may have been considered slightly risqué) suggest she represents one of the thousands of women sex workers in London. Although enhanced with oil paints, the canvas retains the sharp outlines of an etching, particularly in the suggestions of the passing vessels. The influence of Velázquez, Rembrandt, and the sculptures of ancient Greece, on Whistler can be identified in his take on Wapping.

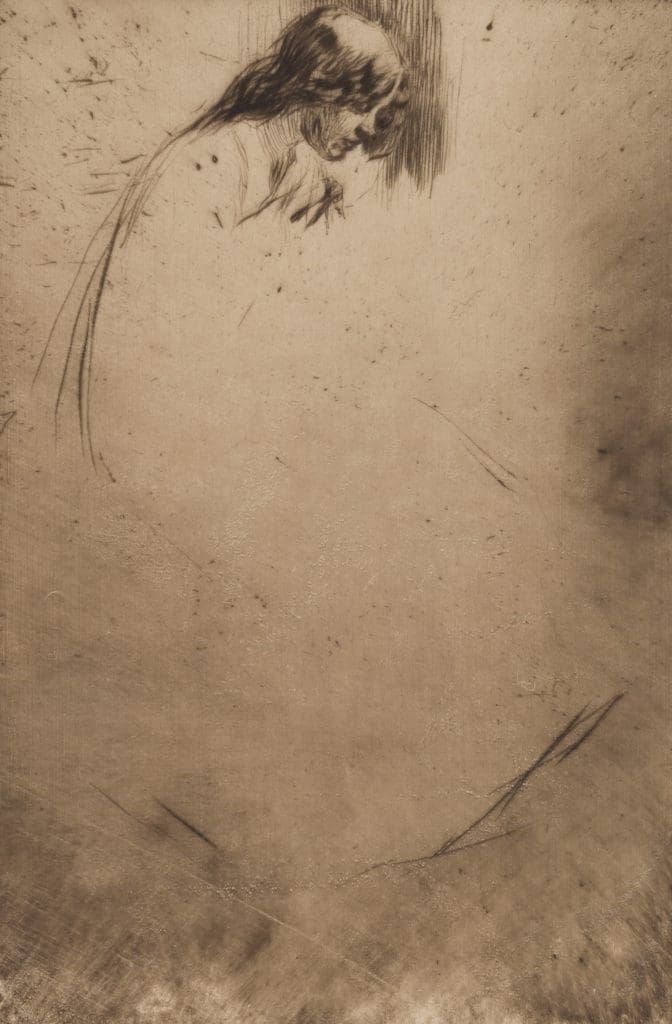

The copper-plate etchings that he created at this time capture scenes of rickety wooden wharfs, jetties, warehouses, docks, and yards. There is an etching of Rotherhithe with similar composition to the oil painting, and a drypoint of Ratcliffe Highway, a seedy street north of Wapping. Whistler’s skills as a printmaker allowed him to make finely nuanced images of Joanne.

Whistler and Hiffernan spent the summer and autumn of 1865 at Trouville on the Normandy coast with Gustave Courbet, who painted Hiffernan’s portrait as La belle Irlandaise, of which he made four versions; in each she looks at herself in a hand mirror while running her hand through that wild, burnished hair. The two men loved painting seascapes– Whistler’s restrained, atmospheric interpretations contrast with Courbet’s more robust ‘paysages de mer.’ Whistler’s misty Sea and Rain is seen alongside several of Courbet, who in 1877 wrote “[painting] the sea… to the horizon, we paid ourselves with dreams and space.”

The artistic legacy of Whistler and Hiffernan is shown by the RA in a section it entitles Women in White. Highlights include The Somnambulist by John Everett Millais from 1871, (Delaware Art Museum), Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Hermine Gallia, 1904, (National Gallery, London) and Symphonie en blanc, 1908, by Andrée Karpelés (Musée Des Beaux-Arts De Nantes.)

Millais closely followed the career of Whistler and especially admired The White Girl, as is evident in The Somnambulist, in which a woman in a nightgown, her hair down and her feet bare, sleepwalks fixedly along a cliff top. The candle in her brass candlestick has just gone out, leaving moonlight to illuminate her way. Millais, who loved opera, is speculated to have derived the theme from La Sonnambula by Bellini, where in the final scene the grief-stricken heroine sleepwalks across a dangerously unstable bridge.

Andrée Karpelès (1885-1956), the daughter of a Greek merchant named Jules, swathes her dark-haired model of Symphonie en blanc in a luxurious gown with generous décolleté and a knowing look. Andrée’s family settled in Calcutta , where she became fluent in Hindi and Bengali. She studied in Paris and exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants from 1907 to 1914. From 1910 she was influenced by the Bengali polymath Rabindranath Tagore with whom she maintained correspondence until the latter’s death in 1941.

In his portrait from 1851 of Lady Dalrymple, George Frederic Watts likened the poise of his favourite model Sophia Dalrymple to a Greek sculpture. She is in a free-flowing dress of a type which apparently would have appealed greatly to Watts, who studied the Parthenon marbles at the British Museum during his youth. Sophia is seen standing on the balcony of Little Holland House, Kensington. She was widely admired by men from literary and artistic circles, including William Makepeace Thackeray, Edward Burne-Jones, and Rossetti. Watts (1817-1904) was born in Marylebone, London, the son of a poor piano-maker. He learned sculpture from the age of 10 and enrolled as a student at the Royal Academy at 18. His first wife later lived with EW Godwin who had married Beatrice Philip, later the wife of Whistler.

Other paintings by British artists that exemplify the theme of the woman in white include Rosetti’s Ecce Ancilla Domine! (The Annunciation) of 1849-50, from the Tate.

Joanna was the third daughter of John Heffernan (or Hiffernan), a schoolmaster, and Catherine Hannan of Limerick. The impoverished family fled Ireland for London by 1843 to escape the Great Famine. Joanne was already modelling for artists when she met Whistler. His family disapproved of Hiffernan’s social status, and of them openly living together in a non-marital relationship: when Whistler’s mother arrived from America for a visit in January 1864, Hiffernan was packed away to other lodgings.

In January 1866 Whistler left suddenly for a nine-month stay in Chile, possibly because of the recent conviction of his friend John O’Leary for Irish republican activity. Before leaving, he made a will in Joanne’s favour and gave her power of attorney while he was absent in Chile. In 1879 Maud Franklin, Whistler’s then companion and main model, accompanied him to Venice leaving ‘Aunty Jo’ and Agnes to continue looking after his son Charlie Hanson. In 1888 Whistler married Beatrice Godwin.

After several months suffering from bronchitis, Joanna Hiffernan died in Holborn, with her sister by her side, on July 3, 1886.

Born in Lowell, Massachusetts, Whistler in 1855 settled in Paris, where he studied art and associated himself with avant-garde artists including Édouard Manet, Rossetti, Henri Fantin-Latour, Courbet, and Claude Monet.

Co-operation between the Royal Academy and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, has produced a fascinating show. It is curated by Margaret MacDonald, Professor Emerita and Honorary Professorial Research Fellow, Glasgow University, in collaboration with Ann Dumas, curator at the Royal Academy and consulting curator of European art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and Charles Brock, associate curator at the department of American and British paintings at the National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Captions in detail:

Symphony in White, No I: The White Girl. 1862. Oil on canvas. By James McNeill Whistler. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Harris Whittemore Collection.

Wapping. Oil on canvas. 1860-64. By James McNeill Whistler.. National Gallery of Art, Washington, John Hay Whitney Collection.

Jo, La Belle Irlandaise. Oil on canvas. 1865–66. By Gustave Courbet. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, HO Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. HO Havemeyer.

Jo’s Bent Head. Drypoint, printed in dark brown ink on laid paper. 1861. By James McNeill Whistler. Collection of the University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor. Bequest of Margaret Watson Parker.

On the right: Symphonie en blanc. Oil on canvas. 1908. By Andrée Karpelès, Musée des Beaux-arts de Nantes. Left: The Somnambulist. Oil on canvas. 1871. By John Everett Millais, 1871. Delaware Art Museum.

Photograph of Whistler. Carjat et Cie. C 1864. Carte de Visite, mounted on card. University of Glasgow Library ASC.

Lady Dalrymple. Oil on canvas. By George Frederic Watts. 1851. © Watts Gallery Trust.

The Artist in His Studio. Oil on paper mounted on panel. 1865/66 and 1895. By James McNeill Whistler. The Art Institute of Chicago, Friends of American Art Collection.

Ecce Ancilla Domine! Oil on canvas. 1849-50. By Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Tate: Purchased 1886. Photo: Tate.

Whistler’s Woman in White: Joanna Hiffernan is at the Jillian and Arthur M Sackler wing of the Royal Academy until May 22,2022.