By James Brewer

The past two years have been a test of courage for everyone – and artists are among those who have come with flying colours through the pressures of living during the pandemic.

An exhibition which opened on the second anniversary of the first UK lockdown celebrates the way eight artists closely connected to the London scene coped with the mental and physical challenges that were sprung upon them. Their concepts, many in coded autobiography, range from the assembling of totemic ‘found objects’ to the symbolic meaning of shipping paraphernalia, to the dynamism of quantum computing.

Things will Continue to Change is sensitively and with clarity put together by international curators Anna McNay and Perdita Sinclair, selecting artists who refused to hide their feelings but aimed straight to the heart of new discourses in painting, sculpture, and digital media, engaging boldly with the character of the time.

It is hosted by the Koppel Project, a charity established in 2016 in central London to support early and mid-career artists with 100 subsidised studios and short- and long-term galleries, and funding and support for exhibitions.

The theme for the exhibition was born from a drawing by David Shrigley entitled Things will Continue to Change and out of just how much has changed since March 2020. Shrigley is known for encapsulating in his satirical, cartoon-like works the hard truths of contemporary reality.

The artists featured here kept the torch burning even after Chancellor Rishi Sunak declared: “everyone is having to find ways to adapt and adjust to the new reality and that is what we have to do.” His ITV interview in October 2020 was at first reported to relate to creative professionals, but it was quickly clarified that the Chancellor’s comments were about employment generally and not specifically about the music or arts sector.

Joint curator Anna McNay writes in the exhibition catalogue: “Perhaps the greatest irony of Rishi Sunak’s comment, and the government’s advertisements during the first year of lockdowns about creatives retraining, is that it is precisely to art that so many people have turned to help them get through this turbulent and destabilising time.”

Opening of the new show confirms that those who pursue art as a calling were eager to spring back to life as the doors prepared to open again to public display of their wares.

A deep respect for Planet Ocean, both in its physical aspect and as a metaphor for the vagaries of society, is evident in the show. Most visibly, Perdita Sinclair depicts in dramatically confident hues a rudimentary but robust vessel freighted with a clutter of what seems to be chaotic meaning. She gives her work the title Die Eule und die Miezekatze – the German for The Owl and the Pussycat. Perdita admits to being obsessed with deep sea and shipyard markers, such as buoys and equipment, which in this instance became “the manifestation of lots of things going on in my head: serious things, and frivolous things, and it is all mashed together. With the lockdown, I felt a bit adrift, … with a feeling of being unmoored.”

With her paintings sometimes “setting sail into the middle of the ocean,” she focuses on how humans interact and impact upon the environment and complex eco-systems such as on deep sea vents, infrared in flowers, climatic changes in the oceans and starfish reproduction systems. She had a “fantastic” residency with Sail Britain (an arts project which since 2015 has pioneered sailing as creative exploration with participants “learning new skills and about life at sea” to “explore our marine environment, culture and heritage, and highlight the beauty and importance of our oceans.”) She spent a week going up and down rivers and eventually the Thames on the Sail Britain boat, trawling for microplastics. Her other projects have included working with scientists on seed dispersal, being the first artist in residence at the Millennium Seed Bank with scientists at Kew.

For Libby Heaney new developments in technology are her canvas. She “uses tools like machine learning and quantum computing against their ‘proper’ use, to undo biases and to forge new expressions of collective identity and belonging with each other and the world.” This is seen in her contribution Teletities (study of quantum entangled relations between images) which is a contrarian application of quantum computing as both medium and subject matter – she claims to be the only artist in the world using it as a functioning artistic medium. By this means, she “hybridises bodies, voices and identities.”

She has been experimenting for several years with quantum computing, which employs the laws of quantum mechanics to solve problems too complex for traditional computers. Quantum theory explains the behaviour of energy and material on the atomic and subatomic levels; quantum entanglement describes the quantum states of two or more objects with reference to each other, even though the individual objects may be separated.

Entanglement is a scientific term but Libby engages with it in a poetic sense. No fully fledged quantum computer is yet in existence, but the technology has the potential to achieve results and speeds impossible with current computing. Libby says that this new system will probably accelerate in an opposite way to slow things down and look at strong relationships between different entities. The video she presents at the exhibition is very slow and at some point the images become entangled with each other.

She is contemporaneously running a solo exhibition of a 360-degree immersive installation, a huge artwork entitled Ent- which explores the transformations quantum computing is expected to bring to everyday life. Ent- which opened on February 10 at Schering Stiftung in the German capital, was commissioned by Light Art Space, Berlin, and will run until May 1.

Ent- is a quantum interpretation of the central panel of Hieronymus Bosch’s triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights (c 1490–1510). Visitors enter a black cube in which a 360-degree projection takes them through the layers of Bosch’s painting – sky, buildings and landscapes, and water. Libby has used quantum code to manipulate and animate her own watercolour paintings, creating hybrid creatures inspired by Bosch’s medieval monsters, landscapes that seem to shift and breathe, and exploding structures that float and re-form. For her, Bosch’s adjacent depictions of heaven and hell provide an analogue for the double-edged potential of quantum computing

In works such as The Inner Space of Solitude, Carol Robertson says: “The power and beauty of geometric form and detail provides me with a catalyst for ways to make art.” Throughout the pandemic she has gone back to the geometric form of the circle for “solace and self-expression.” Carol says: “Geometry allows me to concentrate on the essential. It allows me the freedom to channel sensory or poetic material through its refined parameters. Over time my work evolves in tandem with whatever is happening in my life, emotionally, spiritually, intellectually, and physically.” In this show, there is one darker work which reflects the gloom of the early days of lockdown, and another painted later in an atmosphere of optimism.

Clare Chapman produces work that finds beauty in the dark and disturbing. Some of her subjects resemble the pus-filled pods or cocoons from which aliens and other horror film staples burst forth, others are more abstract, uncertain outlines in fleshy colours that unnerve without us quite knowing why. The atmosphere of anxiety around an unseen contagion points to an intrusion of visceral chaos, she says.

Matthew Burrows, who early in the pandemic launched the scheme #ArtistSupportPledge is fascinated by gates and thresholds as boundaries controlling and ordering the world. He produces paintings in which “colours and images hover on the edge of description, slow to reveal complex structural spaces filled with marks, shapes, and pigment.

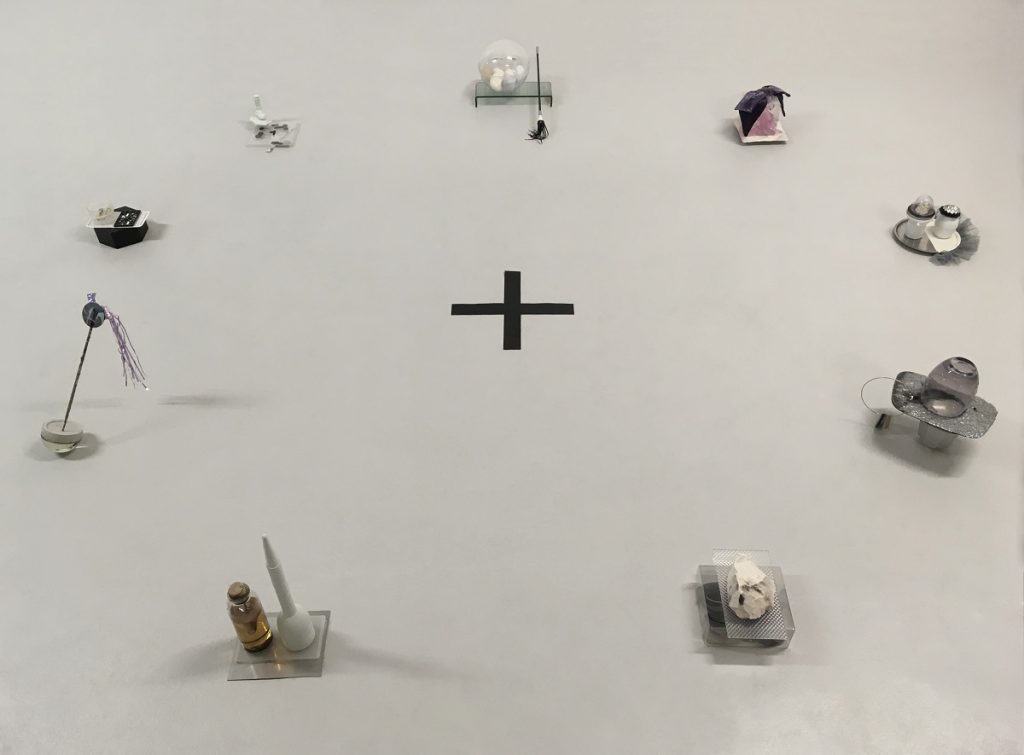

As with some of her fellow artists, Suzanne O’Haire uses her practice “to unscramble and try to make sense of the many fears that swamp my head.” She collects “street treasure” to be ordered, sorted, tried, and reimagined in the studio and instilled with personal narratives and references, from the mundane to the esoteric, as with her floor-level installation Coping Mechanisms,. The installation is built around the number nine, symbolic in numerology of endings and beginnings. This is typical of her assemblages “where a system, numerological element or notion of magical thinking plays an underlying and consolidating role.” Conjuring her work from defunct matter is “perhaps a way of filtering an external, over-stimulated and saturated world internally, or at times endeavouring to make sense of the chaos – these days increasingly so.”

A recent graduate of the RCA, Judith Burrows is a multi-disciplinary artist, photographer, and award-winning filmmaker,

Reflecting the time of insecurity and global uncertainty, her work – currently making sculptural use of steel and organic matter that takes on “a filigree of delicate rust” – prompts a dialogue between living organisms and the unstable manmade. The exchange through corrosion and decay creates narratives in the form of a scientific experiment.

Judith’s recent shows include the Solo RCA Graduation Show, Gallery 40, London (2021); the 168th Royal West of England Academy Open Exhibition, Bristol (2020) and Beyond other Horizons, Iasi Palace of Culture, Romania (2020).

Alison Goodyear works within an expanded understanding of the painting tradition – including physical and digital paint, virtual reality, augmented reality and moving-image film – to create abstract works as immersive encounters. Her starting point is mapped and traced images of her physical paint palette, so they unfold as new territories akin to an alien landscape. Her recent work highlights the temporal qualities open to virtual reality painting, compared with traditional painting.

Anna McNay has curated many exhibitions in London and internationally, most recently including Julie Umerle: Recent Paintings at Bermondsey Project Space; Beyond Other Horizons. Contemporary painting made in Britain and Romania: 40 British and 40 Romanian artists at the Iași Palace of Culture, Romania (2020), co-curated with Peter Harrap and Florin Ungureaunu; and Made in Britain | 82 Painters of the 21st Century at the National Museum, Gdansk, Poland (2019).

Perdita Sinclair has been a curator at the Window Gallery at Phoenix Art Space, Brighton, for the last two years. She co-curated the exhibition Past, Present and Future at Plan Gallery, Dusseldorf, and worked with Lan Art to help select and organise other UK artists for a UK/Chinese exhibition in Suzhou, China.

Complete list of artists in the new show: Judith Burrows, Matthew Burrows, Clare Chapman, Alison Goodyear, Libby Heaney, Suzanne O’Haire, Carol Robertson and Perdita Sinclair.

A rehang midway in the show calendar, installing similar but different works by the same artists, will emphasise the notion of change. Alongside the artists’ works, QR codes in the gallery link to creative responses by KS4 pupils from Addey and Stanhope School, Lewisham.

Anna McNay says: “Things will indeed continue to change as we look towards an uncertain future, and artists are often a good barometer for predicting which way these winds will blow.”

Things will Continue to Change Is at The Koppel Project Hive,“a hub for creativity and innovation,” the project’s longest running site, on weekdays until April 29, 2022, at 26-30 Holborn Viaduct, London EC1A. there will be a panel discussion on April 7 at 6pm. https://thekoppelproject.com/

___

Updated 16 March 2022 20:15 GMT