Kyōsai: The Israel Goldman Collection at London’s Royal Academy

By James Brewer

His nickname was the Demon of Painting. Kawanabe Kyōsai (1831–1889), Japan’s most daring, exciting, and feted painter of the late 19th century, turned out hanging scrolls, decorative screens and album leaves of exquisite detail on an industrial scale, just as the modern industrial revolution was beginning to shake the structures of his country’s society. After centuries of isolation, the country suddenly opened to merchant shipping and trade from the West in 1854.

Kyōsai’s artistry will be a thrilling discovery for many admirers of Japanese culture in the western world. They will be following in the footsteps of those who – like Van Gogh and Whistler over the past two centuries – marvelled at Katsushika Hokusai’s woodblock print Great Wave of fishermen’s flimsy boats in deadly peril from a cresting wave symbolising the power of the sea. That was two-way traffic: Japanese artists including Kyōsai were greatly interested in European art.

Let us not confuse Kyōsai with others of his time, though. Considered by some to be a successor of Hokusai, Kyōsai plays with a different genre taking in a multitude of themes, and outrageously so when he deals with erotica and bodily functions. It requires close-up inspection to appreciate the finely detailed, minute brush flourishes that add character to the humans and animals – battalions of frogs, a Zen priest dancing on the head of a skeleton, whimsical cats — that are his subjects. His art bears comparison with few others – in a different context, one might include the 18th century London printmaker, cartoonist, and satirist William Hogarth.

Israel (known to his friends as Izzy) Goldman, a 1958-born London-based collector and dealer in Japanese prints and paintings, is lending a sumptuous selection of his Kyōsai treasures to the Royal Academy for a show that runs until June 19, 2022.

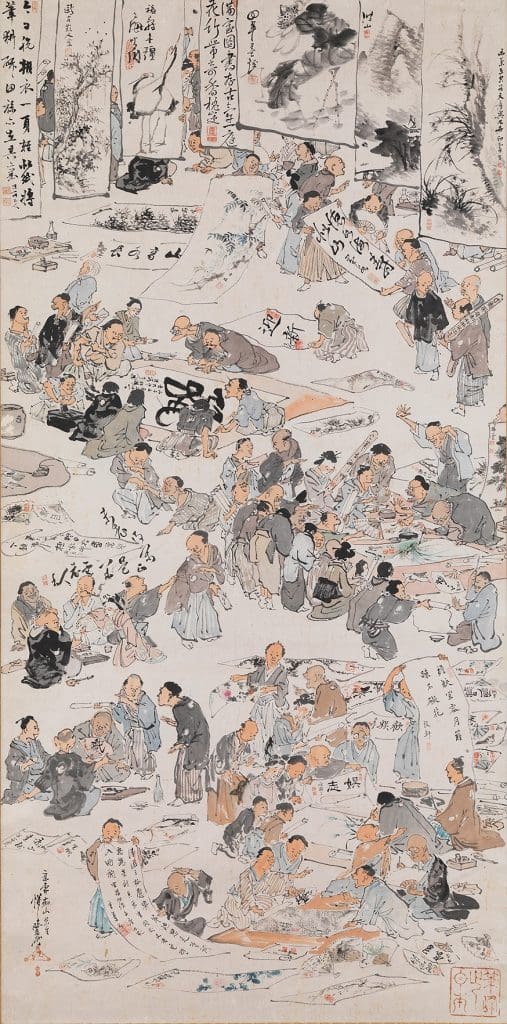

At the heart of Kyōsai’s fame was his mastery of sekiga, or spontaneous paintings, which he whizzed out at calligraphy and painting parties known as shogakai. Parties is the operative word, for the gatherings were often fuelled by copious amounts of alcohol. Kyōsai found it hard to keep away from the fermented rice drink, saké which contains around 15% alcohol. His habit is credited for bringing out the artist’s expressive and provocative gifts.

“Under the influence of BACCHUS [the Roman god of wine and revelry] some of his strangest fancies, freshest conceptions and boldest touches were inspired,” wrote Josiah Conder (1852-1920) a British architect living in Japan who became one of his students and closest friends. Known as the father of modern Japanese architecture, Conder was hired by the Meiji government following introductions by a former employee of the trading company Jardine, Matheson & Co, winning official contracts from the administration and from the founding family of the Mitsubishi group. Besides his enthusiasm for Japanese art, Conder was an aficionado of Kabuki theatre and dance.

The country had in 1854 thrown open to foreigners the port of Shimoda (100 km southwest of Tokyo, the landing place of several of US Commodore Matthew Perry’s menacing “black ships,” warships he assembled to force the Japanese to end their isolation and enter diplomatic relations with the Americans. This was followed soon afterwards by international trade through the ports of Hakodate, Yokohama, and Nagasaki.

In addition to Josiah Conder, Kyōsai met French industrialist Émile Guimet, the founder of the Musée Guimet, and other western artists, writers, and diplomats. We this because Kyōsai published a self-illustrated, semi-autobiography, Kyōsai gadan, in 1887, and other written records about him are abundant.

Despite drink consumed by the master and his acolytes, his draughtsmanship flowed apace (in 1873 he hosted a shogakai at which he is said to have produced 200 works), and was celebrated by event flyers, newspaper articles and anecdote. In contrast to the spontaneous works, his meticulous studio paintings reflected a formal training, in a style which nevertheless challenged artistic convention. He turned his hand with immense flair to any subject from the realms of social customs, societal upheavals, religious mythology, fable, and erotica.

Kyōsai was born the son of a samurai in the city of Koga, 60 km north of Tokyo, and as a child prodigy a pupil of the ukiyo-e artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798-1861). The term for woodblock prints ukiyo-e means ‘floating world’ and is synonymous with Hokusai’s Great Wave. Kyōsai was trained at a branch of the renowned Kano school, and by the age of 11 had earned the ‘demon’ tag. Kyōsai was never a political rebel but incorporated new elements into traditional studies and was acutely aware of the great social and cultural changes swirling around him. Some of his works echo the tumultuous last period of the Tokugawa or Edo shogunate which had dated from 1603 and was ended by young samurai seizing power and handing control to the emperor Meiji. The 1868 Meiji Restoration abolished the feudal system, enacted a constitution, brought in a parliamentary system, created a national army, and inaugurated a transport system. When rebellions in the next few years broke out, and were suppressed by the national army, Kyōsai sharply satirised those conflicts.

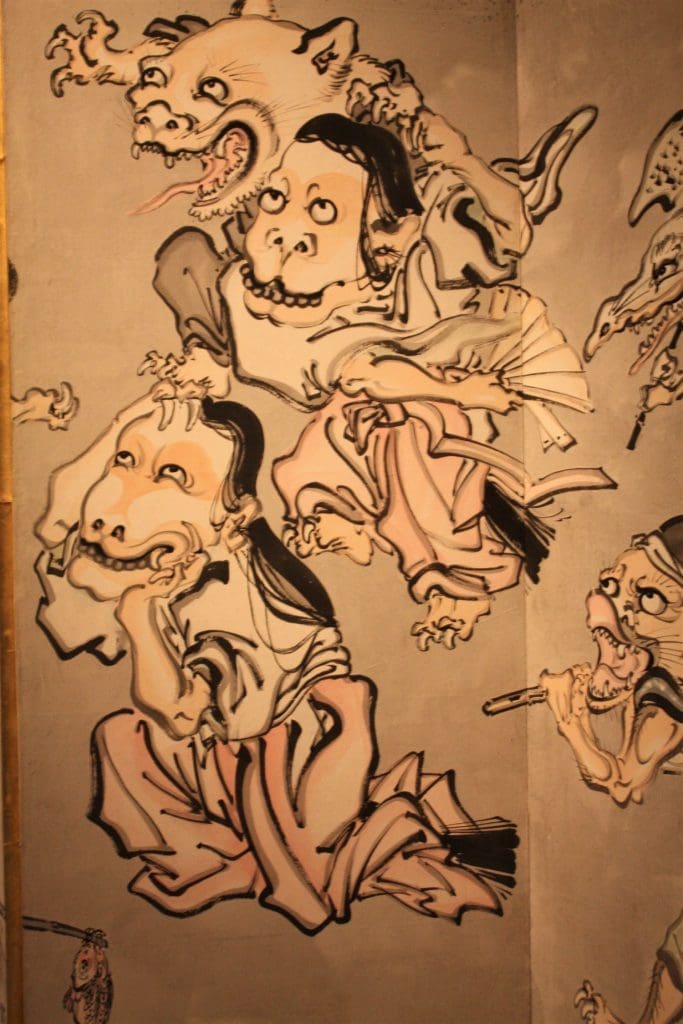

One of the first, startling sights greeting the visitor to the Royal Academy show — the first solo exhibition of Kyōsai’s work in the UK since 1993 – is a pair of 3 metre folding screens, which bears the title Night Procession of One Hundred Demons. The subject of ‘possessed objects’ of everyday use that turn into scary monsters (yokai) comes from folklore over 1,000 years. The screens depict a misty night in which monsters scurry in pandemonium, scattering in panic when confronted by the rising sun.

Among beautifully-presented work is a silk hanging scroll, Two Crows with Crow Gourd (karasu–uri) in ink and light colour from around 1884–9. For Kyōsai, crows symbolised his success. He had won top prize at the Domestic Industrial Exposition in 1881with the painting Winter Crow on a Withered Branch. As his crow images became popular both in Japan and the West, Kyōsai made a seal with the inscription “flying over all lands,” suggesting that his crows were spanning the world and spreading his reputation.

Among other memorable examples from the world of birds and animals is the sketch on paper Cat with a catfish head, while a preparatory drawing of two young women playing with cats seems to reveal the artist’s gentler side.

Humanised animals are used to impart humour, overcome strict political censorship, or treat delicate topics. Frog School, an album leaf from the early 1870s depicts a frog teacher pointing to a lotus-leaf chart while giving a class to two frog pupils seated on a wooden log. This doubtless refers to Japan’s establishment in 1872 of a national educational system, with the first elementary school in Tokyo teaching by western methods including wall charts. Kyōsai’s first sketch, at the age of three, had been of a frog caught for him by a servant. There are frogs galore in Fashionable Picture of the Great Frog Battle from 1864 which mirrors an episode in the resistance by the Tokugawa.

Drama on another scale is shown in Hell Courtesan (Jigoku–dayū), Dancing Ikkyū and Skeletons, a silk hanging scroll of the story of a high-ranking courtesan (dayū) in Sakai, a port town near Osaka, who had an image of hell (Jigoku) embroidered into her gown, hoping to make amends for her sins and eventually be reborn into paradise. The gorgeously attired courtesan looks over her shoulder at the wild Zen priest Ikkyū dancing on the head of a skeleton which is playing the traditional three-stringed instrument shamisen. The priest, repulsive at first to the courtesan, answers her questions about heaven and hell, and leads her to enlightenment.

Delving again into legend, Kyōsai summons up A Beauty in Front of King Enma’s Mirror in colour and gold on a silk hanging scroll. In this magnificent scenario, the king of hell is using his magic mirrors to gaze into the lives of men and women so that he may pass judgment on them and on the piety of their families, and that the person under examination will be consigned to heaven or hell.

Kyōsai has much to say on the introduction of western culture to Japan. Skeleton Shamisen Player in Top-Hat with Dancing Monster (1871-78) caricatures a foreigner as a top-hatted skeleton playing the shamisen to a mini-monster.

On another front, Kyōsai fearlessly painted comical shunga (sexually explicit images), often impromptu in front of his audience. Unrestrained depictions of sex were an opportunity to give free rein to his wit and sarcasm.

For long out of fashion, Kyōsai today has a vibrant legacy among modern manga (comic magazines and graphic novels), and his followers include tattoo artists and contemporary painters.

Japan’s ambassador in London, Hayashi Hajime, said at the opening of the exhibition: “Although Kyōsai was long overshadowed by earlier ukiyo-e artists, notably two gigantic figures, Hokusai and Hiroshige, he is now justly celebrated as a pre-eminent artist in his own right and particularly as one who was able to bridge traditional art and popular culture. He lived through turbulent times, which included the collapse of the Tokugawa Shogunate and Japan’s opening to the outside world in the latter half of the 19th century. During this period, Europeans including Britons started arriving in Japan, and Kyōsai developed friendships with some of the foreign advisers employed by the Meiji Government, such as the British architect Josiah Conder.”

This stand-out exhibition is curated by Dr Sadamura Koto, who is Robert and Lisa Sainsbury Fellow at the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures and visiting researcher in the Asia Department at the British Museum; and Israel Goldman, in conjunction with Dr Adrian Locke, chief curator of the Royal Academy.

Israel Goldman has been collecting Kyōsai works for almost 35 years and holds the world’s largest private collection of them, having always been intrigued by Kyosai’s skills and sense of humour. He developed his love of Japanese art at an early age, buying his first print in London at the age of 11. He launched his career as a dealer after graduating from Harvard College in 1981 and is now one of the foremost businesspeople in the field of Japanese prints, paintings, and illustrated books. He has curated three exhibitions of Kyōsai’s work in Tokyo.

He became an associate director of the Ukiyo-e Print Dealer’s Association of Japan in 1988 and was a founding member of the International Fine Print Dealers’ Association.

The exhibition is accompanied by an illustrated publication written by Dr Koto and a book on Kyōsai’s animal images, Kyōsai’s Animal Circus.

All pictures shown except the photo of Kawanabe Kyōsai are from the Israel Goldman Collection.

Captions in detail:

Hell Courtesan (Jigoku–dayū), Dancing Ikkyū and Skeletons, 1871–89. Hanging scroll: ink, colour, and gold on silk. Photo: Ken Adlard.

A Beauty in Front of King Enma’s Mirror, 1871–89 (1887?). Hanging scroll: ink, colour, and gold on silk. Photo: Ken Adlard.

Night Procession of 100 Demons. Ink and light colour on paper.

Night Procession of 100 Demons. Detail.

Sparrows at a calligraphy and painting party. Ink and light colour on silk.

Preparatory drawing of two young women playing with cats.

Photo of Kawanabe Kyōsai. Kawanabe Kyōsai Memorial Museum.

Cat with a catfish head. Ink and light colour on paper.

Frog School, early 1870s. Album leaf: ink and light colour on paper. Photo: Ken Adlard

Two Crows with ‘Crow Gourd’ (karasu–uri), c 1884–9. Hanging scroll: ink and light colour on silk. Photo: Ken Adlard.

Calligraphy and Painting Party (Shogakai), c May 1876-spring 1878. Kawanabe Kyōsai and 54 others. Hanging scroll: ink and light colour on paper. Photo: Ken Adlard.

Kyōsai: The Israel Goldman Collection runs until Sunday June 19, 2022, daily except Monday, at the Royal Academy of Arts, London.