By James Brewer

Who is that woman in the window? Artists have since ancient eras framed women, literally, in stories and enigmas that evoke in the viewer deep and sometimes troubling curiosity, empathy and admiration. Rembrandt did so in 1645 in one of his most intriguing compositions; the Impressionists, Picasso and many other modern masters employed this device. This was long after the woman/window appeared as a scene carved in a palace wall in Mesopotamia, and in a comedy painted on a wine jar in the Hellenistic period…

The new exhibition at the ever-inventive Dulwich Picture Gallery shows the window is a mirror, too, of the power dynamic between artists and their models and muses: what were the personal and often intimate relationships before, during and after each sitting?

When Edgar Degas in 1872 finished an oil painting of a model in shadowed profile seated against a bright, light-flooded window, he told his friend Walter Sickert, another prominent artist of the time, that the model was a starving sex worker. Degas had paid her with meat which she “immediately devoured raw,” he said. The painting, like many others, is titled simply Woman at a Window.

This is one of the many revealing stories thrust into the spotlight in Reframed: The Woman in the Window, a marvellous miscellany of artworks from ancient civilisations to the present day. Bold realism is a common feature, showing up the advantages of the genre, and ever-present is the mystique of the female gaze.

Seduction, spirituality – the exhibition explores the window motif in Mediaeval depictions of saints (the window types did not always match styles of the time) and the image of the Virgin Mary as a window to heaven – and the afterlife take turns as themes through the exhibition, for which more than 40 works have been chosen in sculpture, painting, print, photography, film, and installation art to examine hugely varied cultures made evident through one window after another.

In the first room is related a ribald story of more than 2,000 years ago from Greek lore. It is imprinted on a red-figured bell-krater (wine-bowl) made in Paestum, a city on the west coast of Italy, 80 km south of modern-day Naples and whose name as a Greek colony was Poseidonia, meaning sacred to the god of the sea and protector of seafarers, Poseidon. The British Museum has lent this pot made some time between 360 and 340 BCE which pictures a comedic scene in which an old man climbs a ladder to visit a hetaera, an entertainer and sex worker. She can be seen in a window, in a purple embroidered chiton (tunic), her face painted white looking down at the man who will offer her apples – fruit related it seems to about the seductive power of female beauty. Such a jug was used for mixing wine and water at drinking parties (symposia) where hetaerae entertained men.

Even older (900 to 700 BCE) is an ivory panel carved by a Phoenician showing a woman at a temple window, again lent by the British Museum. It is from the many-splendored 28,000 sq m Northwest Palace at Nimrud (in the territory of modern-day Iraq) built by Ashurnasirpal II on the east bank of the Tigris. The woman, with the attributes of Western-Asian goddesses of beauty, fertility, and love, has been associated with the practice of ‘sacred prostitution,’ but the exact significance of the scene is unclear. She has a full Egyptian hairstyle and wears a necklace. The curators say the window seems to act as a portal between secular and sacred worlds; it has also been described as a proxy for the female anatomy.

Dulwich’s own Girl at a Window (1645) by Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn was the initial point of inspiration for the exhibition, throughout which the subjects tend to be painted from life rather than from imagination. In the Rembrandt composition, the subject leans on a stone window ledge, turning her head towards the viewer while self-consciously fiddling with her necklace. A surviving drawing reveals that Rembrandt painted the girl from life, but no record of her identity has been found. Over the centuries, she has been variously described as Rembrandt’s lover, an allegorical or Biblical figure, a servant girl, a bride, or a courtesan. The majority opinion is that she is a servant, with her rosy, tanned complexion and brown arms suggesting that she worked outdoors.

Windows within windows: a French art theorist and early owner of the Rembrandt work, Roger de Piles (1635-1709) claimed that he put the painting in his window and passers-by mistook it for a real girl. While this story was probably not true, it speaks to Rembrandt’s ability to create lifelike portraits and he continued to favour this pose throughout his career.

A pupil of Rembrandt, Gerrit Dou, appropriately joins him in the exhibition, with A Woman Playing a Clavichord. Dou was so popular with 17th and 18th century collectors they valued him even more than his one-time master. Here the window with the tapestry curtain drawn back lets sunlight onto a scene raising questions, as the depiction of musicians was associated with love. The young woman pauses in her playing, perhaps welcoming her lover who will accompany her on the viola da gamba. An empty birdcage hangs from the ceiling… Ah, the birdcage! It is there in so many paintings of the genre. Does it symbolise a woman’s body trapped and subservient in convention?

Two hundred and fifty years later we find the Austrian expressionist Oskar Kokoschka siting a birdcage at the top right of a room which is the setting of his 1908 lithographic postcard in the Vienna Secession style Woman at a Window. Much can be read into this night-time scene which shows a woman sitting before a window with an open book on her lap. Beyond the window, the curving forms of the moonlit landscape evoke freedom, but the ironwork in the balcony and the bars of the birdcage suggest that the woman and bird are both uncomfortably confined.

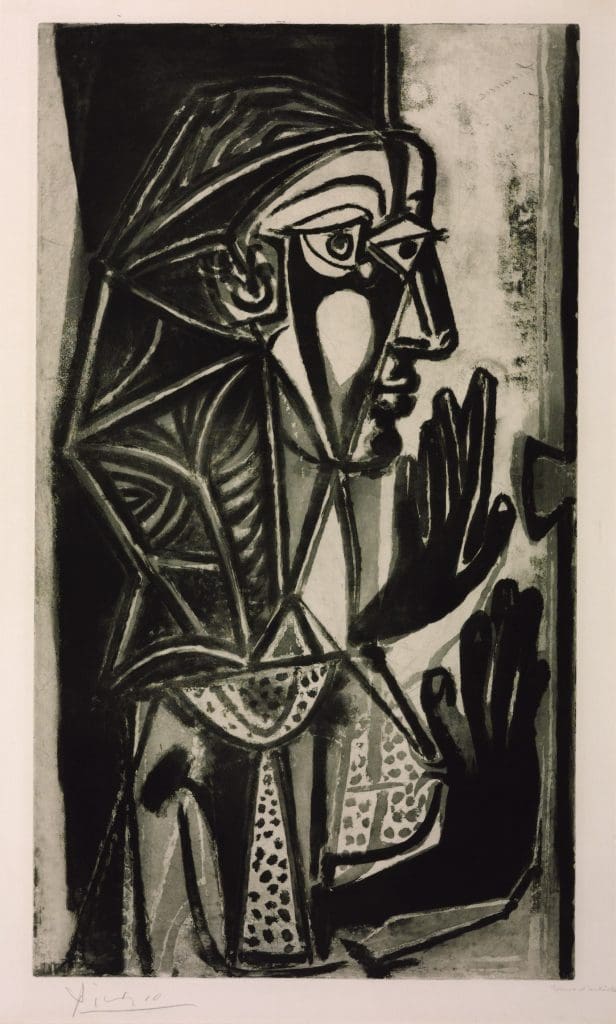

Pablo Picasso in his aquatint La Femme à la fenêtre (Woman at the Window) from 1952 represents his partner-muse, the artist Françoise Gilot, in abstract form and silhouetted against the white windowpane. Her posture suggests anticipation or anxiety, perhaps reflecting the final months of their tumultuous ten-year relationship. Picasso continued to treat her badly, even after they broke up, discouraging galleries from buying her work.

In a view which emulates Johannes Vermeer’s Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window (from 1657–59) the photographer Tom Hunter in 1997 movingly pictured Woman Reading Possession Order in his series Persons Unknown. He substitutes the Golden Age oil painting’s sumptuous interior with the simplicity of a squatter’s home in Hackney, east London, and the love letter with an eviction notice. Despite the tension evident, the light from the window, illuminating the woman’s resigned face and the head of the baby lying next to her, offers a suggestion of hope. The coldly worded court notice is displayed in a glass frame alongside the photographic work.

The window theme is taken up by among others the German photographer Wolfgang Tillmans, in Smokin’Jo, window. The buzz-hairstyled DJ Smokin’Jo took on her gender-ambiguous stage name as she entered in 1995 an almost entirely male profession. The caption says: “Jo’s composure, focus and distant gaze here suggest the skills that enabled her to navigate gender stereotypes.”

There is a distinct shortage of women artists, as there was for centuries in public display, until the final section of the show which champions the modern woman. Clementina Viscountess Hawarden was among the first female artists to take up the ‘woman in the window’ challenge, photographing in around 1862 one of her daughters kneeling in a pose suggesting longing, against a window.

More recently, while confined to her home, Louise Bourgeois salvaged an old window frame from the basement to create My Blue Sky (1989-2003), representing her lifeline to the outside world and in which a mountainous landscape takes on her artistic concern with female shapes. In Marina Abramovic’s Exchange (1975) and Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Still #15 (1978) the artists place themselves in the role of the woman at the window. While Abramović explores what it means to become a sexual commodity, Sherman considers stereotypes of female representation in popular culture by appearing to transform into one herself.

The exhibition concludes with a poignant epilogue of the effect of pandemic lockdowns which brought a new meaning of ‘woman in the window’ as people in hospitals and care homes were allowed to see their loved ones, even the terminally ill, only through transparent barriers.

The curator, Dr Jennifer Sliwka of King’s College London, said that the show provided insight into the ways artists have taken up the device of the window as a kind of ‘portal’ between realms: the real and the imagined, the sacred and the profane, between this life and the afterlife or between the public and the private. “When you put a man at the window, you know his name. That is so often not the case with women: is she a political heroine, is she a courtesan? Is that woman looking back at us?”

Jennifer Scott, director of Dulwich Picture Gallery, said: “This really is the exhibition for now, as themes of isolation, seclusion and contemplation gain increasing pertinence in a post-lockdown world.” Looking over 3,000 years, it was intriguing to see what it tells us about art, history, and humanity.

Dulwich Picture Galley uses the exhibition to listen to contemporary voices, through a newly commissioned digital artwork with recorded conversations with a group of 50 members of the local community. Dr Scott said: “The gallery is where people can find themselves in art. Everybody’s participation matters.”

Image captions in full:

Girl at a Window. By Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn. Oil on canvas. Oil on canvas. 1645. Dulwich Picture Gallery.

A Woman Playing a Clavichord, By Gerrit Dou. Oil on oak panel. 1665. Dulwich Picture Gallery.

Bell Krater, Paestum. 360-340BC. British Museum © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Woman at the Window. Ivory relief. Northwest Palace, Nimrud (modern-day Iraq) 900 to 700 BCE. British Museum.

Woman at a Window. By Oskar Kokoschka. Lithographic postcard. Published 1908 by Wiener Werkstätte. Victoria & Albert Museum.

La Femme à la fenêtre (Woman at the Window). By Pablo Picasso. Aquatint and drypoint, 1952. © Succession Picasso/ DACS, London 2021. Photo: Tate.

Smokin’Jo, window. Unframed inkjet print. By Wolfgang Tillmans. 1995. © Wolfgang Tillmans, courtesy Maureen Paley, London.

Woman Reading Possession Order. Ibachrome print mounted on board. By Tom Hunter, from the series Persons Unknown. 1997. Courtesy Tom Hunter.

Reframed: The Woman in the Window is at Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, until September 4, 2022