A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography at Tate Modern

By James Brewer

Fly me to the Moon – and then on to Mars. That was the dream of a young woman from Zambia after the southern African country declared independence in October 1964. She was chosen to reach for the stars by an envisioned private space programme which turned out to be a ‘castle in the air’. The ambition to launch Matha Mwamba, her two cats and separately a dozen male teenagers to realms beyond Earth was to remain fantasy, and in any case the cost of such an endeavour would have more than swallowed Zambia’s entire national budget.

What happened to the would-be ‘Afronauts’ is one of the intriguing stories at Tate Modern’s exhibition A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography. The Tate spectacle is a kaleidoscope of African-related studio and creative photography from across the continent and diaspora, often in glowing colours. It shows how creators have shaped photography and video in new directions, building on legacies of past practice while challenging dominant images of the continent and imagining more hopeful futures. Here are 100 works from 36 artists of different generations that illuminate histories, customs, beliefs, identities, and apparel.

It was the buoyant aspirations of a new nation that the Spanish-born photojournalist Christina de Middel aimed at pointing up in the 37 colour photographs she took for her series The Afronauts of 2012 (which is in Tate’s permanent collection). Each take crystallised her reaction to the prospective lunar expedition. In her surrealist images she wanted not to poke fun at the those involved, but to celebrate the optimism of the mission. It was important to her that the progenitor tried in his way — people in Europe would say it was not even worth trying, but in Africa there was a different – and beautiful – attitude.

She was motivated to create her photo series by seeing a YouTube interview with the eccentric Edward Makuka Nkoloso, a science teacher who said he wanted Africa to match the then-giants of the space race, the US and the Soviet Union. Nkoloso founded his unofficial Zambia National Academy of Science, Space Research and Astronomical Research to train his ‘Afronauts’ on a farm 20 miles from the capital, Lusaka. He said he would use a catapult system to fire into space a woman, her cats and a Christian missionary on board an aluminium rocket. He was quoted as saying: “I’ll have my first Zambian astronaut on the moon by 1965.” His team were ‘acclimatised’ to weightlessness in a ‘space-capsule’ — a 40-gallon oil drum rolled down a hill. A document written on a rickety typewriter laments the fate of the scheme… “I’ve had trouble with my spacemen and with my spacewomen. They don’t concentrate on spaceflight. There’s too much lovemaking when they should be studying the moon… Then the woman became pregnant by one of the other astronauts and her parents came to take her back to their village.”

De Middel’s surreal images take up the amateurish feel of Nkoloso’s project. The ‘space helmets’ in her photos were glass domes from old streetlamps, while her 92-year-old grandmother made some of the ‘spacesuits’. A baby elephant (Indian, not African) in a zoo near Alicante added a rarefied feel to some of her pictures.

Fantasy-laden though it is, the Zambia exploit is considered of sufficient curiosity to feature on the website of Royal Museums Greenwich, a group which includes the Royal Observatory and the National Maritime Museum. Meanwhile, Christina de Middel deplores that most pictures from Africa in the media show war and suffering, even though there are other things going on.

The Tate curators say that upon the invention of photography, Africa was broadly defined by Western images of its cultures and traditions. During the colonial period, the Eurocentric lens dominated. For the past 70 years, an indigenous focus has taken over and flourished. This has produced portraits of kings and queens and others who resisted colonialism, proudly bearing their inherited spiritual and cultural identity; intimate scenes of family and community life; and now the impact of the climate emergency including vanishing water resources.

In his series Tipo Passe, based on the Portuguese word for a passport, Angolan-born Edson Chagas presents striking large-scale pictures in the style of passport photographs, with faces covered by masks from African cultures. It is his way of questioning the method of identification which in theory enables migration and movement across borders, at a time when refugees in huge numbers are attempting difficult journeys. Such masks were typically used in religious rituals or with ceremonial costumes, and often connected with ancestor spirits, animals or deities who protected from harm. To take one of Edson’s examples, the mask in his photograph of Pablo P Mbela is characteristic of the Ivory Coast tradition and indicates responsibility and duty. Edson studied photojournalism and documentary photography in the UK and lives in Angola and Portugal. He won international renown by propelling Angola to win the Golden Lion prize for the best pavilion at the 55th Venice biennale in 2013. The nation’s display at the biennale included his digital images of abandoned objects as part of the Luanda, Encyclopaedic City theme.

Another acknowledgement of masquerade activating cultural memory and collective identity is seen in works by American-Nigerian visual artist and performer Wura-Natasha Ogunji. She drew from the tradition of the Egungun Yoruba masquerade, which reveres ancestors and embodies spirits, for her 11-minute video from 2013 entitled Will I still carry water when I am a dead woman? She created a first version of the video in 2011 in Lagos, crawling along the ground hauling water kegs tied to her ankles. The scenario was inspired by the daily task of carrying water at her cousin’s house. While the piece raises questions about the work of women, it is also about labour, basic needs and the politics of change, she says. When do people have an opportunity to rest, reflect, envision, imagine, and enact another way of being? Wura-Natasha, who is of Nigerian descent on her paternal side, was born in the US. For many years she divided her time between Austin, Texas, and Lagos, where she eventually settled and in 2018 opened The Treehouse, an independent exhibition space in the Ikoyi district.

A patchwork of social concerns is embodied in the projects of Accra-based Zohra Opoku. At Tate, on display appropriately is a huge screen-print on cotton of a hand stitched patchwork of seven second-hand fabrics, entitled When We Were Queens and Kings. This 2017 work was bought by Tate in 2021. The material was imported: Zohra sought to highlight the roles played by customary dress and fabric waste in the modern African textile industry and traditional African dress codes. Zohra says that she is “stitching the past into the present to honour ancestry and individuality.” The artist, who is represented by Mariane Ibrahim Gallery of Chicago and Paris, has just had her first show in the French capital, for 10 weeks up to June 3, 2023, following a debut show in Chicago in 2022. Zohra’s personal story is moving and led to her becoming an artist exploring questions of identity. Her East German mother and Ghanian father met in 1975 while they were both studying in then-East Germany. Shortly after Zohra’s birth, her father had to return to Ghana, but her mother was legally forbidden to follow him. Now she seeks to recover the history and culture which she missed inheriting from her father. Zohra makes use in her passion for screen-printing of her previous studies of fashion design.

Observing youths scavenging materials from the electronics dumps of Maputo, Mozambique-born Mário Macilau specialises in long-term projects that photograph life at the social margins. Thus, the ironic title of Breaking News from The Profit Corner series, 2015. The reality of the lives of the ‘treasure hunters’ picking through discarded consumer goods from Europe is harsh. In some of the photographs, the foragers are melting down circuit boards to extract the metals, creating toxic clouds of ash. In the Tate etc magazine, Mário said that at the Hulene rubbish dump “more than a thousand families participate in the intensive labour of garbage collection, sustaining themselves and making a living out of whatever they find to be edible or useable amid the rubbish… With each passing day, the land surrounding the dump is polluted as workers extract valuable materials using environmentally destructive recycling methods, such as the burning of electronic waste.” One morning Mário spotted a broken TV set on the ground. “A young boy who worked at the dump pulled up behind it and asked me to take a photo of him, posing as if he were a journalist presenting the morning news… This boy was one of the loveliest people I have ever met, yet he was living in a site of human negligence. I don’t want people to remember these people, or my country, in this way.”

The exhibition salutes the flourishing of studio photography in the 1950s and 60s, when African nations were gaining independence. Pioneering photographers such as James Barnor in Ghana and Lazhar Mansouri in Algeria pictured families and individuals gathering proudly to have their portraits taken, often for the first time. Barnor, who was born in 1929, opened the Ever Young portrait studio in 1953 in Accra, celebrating his sitters’ youth, elegance and beauty. Joyful and empowering photographs began to reflect the hopes and dreams of a nation. An excellent example is the 1957 picture of four nurses, graduates of Korle Bu Teaching Hospital. The excited commitment of the four women is nobly captured. The hospital, the premier tertiary healthcare facility in Ghana, was established in 1923: its name, in the local Ga parlance means ‘the valley of the Korle Lagoon’. With new facilities and blocks of wards, Korle Bu’s initial 200-bed capacity rose substantially to make it the third biggest of its kind in Africa, with 2,000 beds and 21 clinical and diagnostic departments.

Further enhancing the rich history of self-expression and representation, artists such as Lebohang Kganye, Atong Atem, and Ruth Ginika Ossai delight in the contemporary relevance of family portraiture. Described by London’s Evening Standard in 2020 as one of the leading faces of the new wave of London’s fashion industry, Ruth has worked on shoots with Rihanna, Kenzo and Nike, but equally features young people from her community – such as the student nurses Alfrah, Adabesi, Odah, Uzoma, Abor and Aniagolum, of Onitsha, a river port city in Anambra state. She is influenced by the Nollywood films of Nigeria and is noted for using striking backdrops. Ruth grew up in eastern Nigeria and is now based in west Yorkshire.

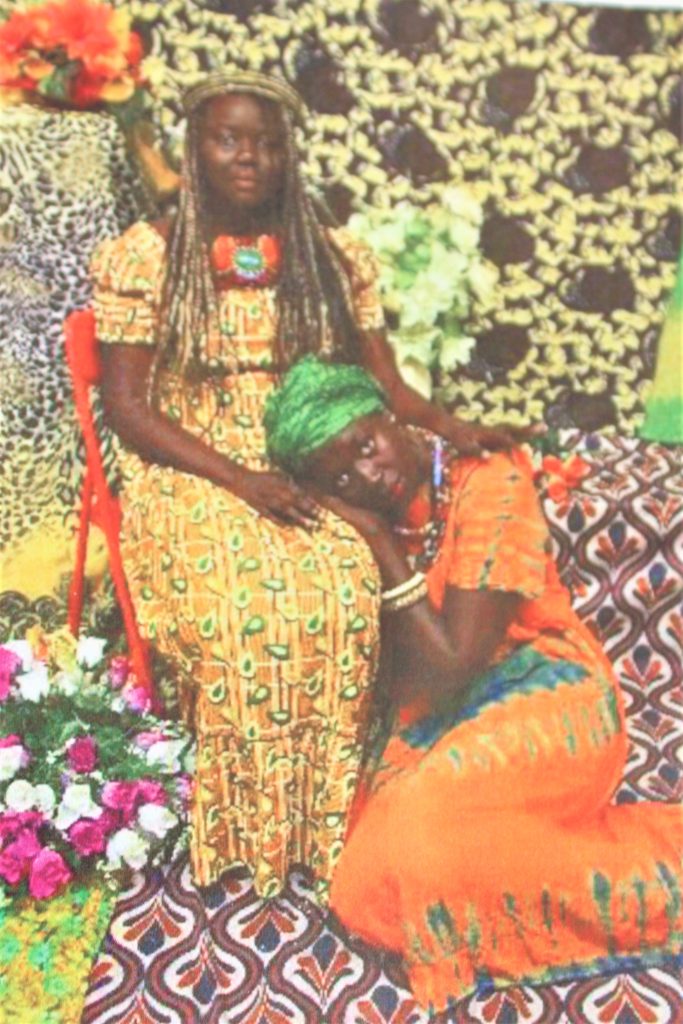

In brightly patterned, staged studio portraits, photographer Atong Atem makes her contribution towards the way Africans are depicted. Melbourne-based Atem is driven by her socially aware reclamation of ethnographic imagery. She speaks of the moment in history when black people took the camera and “chose to photograph ourselves for ourselves” and explores the migrant narratives and postcolonial practices in the diaspora. Her sitters are seen against gloriously coloured sets decorated with intricately patterned fabric, furniture and bunches of flowers, as in her picture of Adut and Bigoa in The Studio Series of 2015. Atong Atem was born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in 1994, lived for a while in the South Sudanese town of Bor, and migrated with her family as a small child to Australia.

The struggle for clean water supplies and its impact on society and especially on women in rural regions is addressed by Aïda Muluneh, ethereally so in her inkjet print Star Shine Moon Glow, Water Life from 2018. Born in Addis Ababa, Aïda graduated from Howard University in Washington DC with a communications degree, majoring in film. She argues that those who live in cities often take for granted their privileged access to water, while those beyond the city grid encounter challenges that not only are risks to their health but also to their ability to help develop their communities. In several regions in Ethiopia, she encountered streams of women travelling on foot, under the burden of transporting water. The time spent fetching this precious commodity for the household holds back the progress of women in society, she says. Each of her pieces is a reflection on how water rights relate to women’s liberation, health, sanitation and education. Aïda’s photography has been published widely and is in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and other institutions. In 2019, she became the first black woman to co-curate the Nobel Peace Prize exhibition and in the following year, she returned as a commissioned artist for the Prize. She founded the Addis Foto Fest, the first international photography festival in East Africa which has been held since 2010.

Captions in detail:

Adut and Bigoa, The Studio Series, 2015. Ilford smooth pearl print. By Atong Atem.

Part of the Tipo Passe series, 2014. C-prints on matte Kodak photo paper. By Edson Chagas.

When We Were Queens and Kings, 2017. By Zohra Opuku. Screenprint on cotton.

Breaking News from The Profit Corner, 2015. By Mario Macilau. Archival pigment print on cotton rag paper. © Mário Macilau, Courtesy Ed Cross Fine Art.

Butungakuna, 2012. By Cristina de Middel. Photograph, inkjet print on paper. © Cristina de Middel.

Star Shine Moon Glow, Water Life, 2018. By Aïda Muluneh. Photograph, inkjet print on paper. Commissioned by WaterAid. © Aïda Muluneh.

Will I still carry water when I am a dead woman? 2013. By Wura-Natasha Ogunji. Single-channel digital video. Fridman Gallery © Wura-Natasha Ogunji. Photo credit Ema Edosio.

Four nurses, Graduates of KorleBu Teaching Hospital Ever Young Studio, Jamestown, Accra, 1957,

Student nurses Alfrah, Adabesi, Odah, Uzoma, Abor and Aniagolum. Onitsha, Anambra state, Nigeria, 2018. Photograph, inkjet print on paper. By Ruth Ossai. © Ruth Ginika Ossai.

A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography is at Tate Modern until January 14, 2024.