Rubens & Women — Dulwich Picture Gallery shines new light on the Flemish master

By James Brewer

Four centuries after the zenith of his fame, it is time for a new narrative about the remarkably prolific Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens, the greatest artist of his day and for long beyond.

Dulwich Picture Gallery’s thoughtfully-presented exhibition Rubens & Women challenges the popular notion that Rubens (1577–1640) painted women only as fleshy and voluptuous beings.

Certainly, the name of the versatile painter, scholar, businessman, confidant of rulers and intellectuals, and diplomat fluent in six languages, who was knighted by the kings of England and Spain, ultimately was appropriated for the term ‘Rubenesque’ to describe ladies who appear with more than generous form in scenes of religious and mythological chronicle.

He based the robustness of such female figures in the tradition of ancient Greeks and Romans, to emphasise their attraction and fertility, and the males he showed were also endowed with more than an average share of flesh.

The Dulwich show covers new ground in re-evaluating the varied and important place in his oeuvre of women, both real and imagined. More than that, it allows visitors to inhabit the multifarious world of Rubens, from his dedication to family and religion, to his popularity and ease among the nobility in some of Europe’s most imposing nations.

It does so by way of 40 paintings and drawings and archive material elucidating the essential ways in which Rubens’s relationships with women nourished his creativity and glittering career. We learn of the role played by his female patrons and members of his family, by his profound faith, and by his artistic beliefs. This assessment is of profound importance because he was to influence many later great artists; in his lifetime he co-operated with among others Jan Brueghel the Elder.

Five years in the planning, this show assembles works from leading museums, with a cast of many women, including his two wives and his only daughter, wealthy nobles clad in fine garments, saints, and mythological goddesses. Many of the masterpieces appear in the UK for the first time to help cast new light on one of art history’s most prominent figures.

Drawing attention to the level of interaction between the painter and the sitter, co-curator Dr Amy Orrock summed up his special gift: “He was a painter not just of women but for women.

His essays were produced just a few years after trailblazing artists in Italy, including Artemisia Gentileschi, were getting to grips with Biblical allegories of virtuous, strong, and pious women.

The women Rubens depicts are not stereotypes or passive figures to be merely observed and should be recognised as enduring and active agents of their own destiny. Many exude formidable hauteur, but their humanity is evident. Rubens paints eyes that magnetise. In the altarpieces, there is a sense of a tangible woman being present. Rubens’s women are no more voluptuous than those of his predecessors. They are simply more life-like, even sensual, their skin convincingly supple and believably warm.

The spectacle opens with a self-portrait from a private collection, the only portrait of a man in the Dulwich exhibition. Painted in Italy, this is the earliest known individual self-portrait by Rubens. Usually on display in the Rubenshuis, Antwerp, it is a preparatory study for his likeness that he incorporated in the most important commission while at the court of the Gonzagas in Mantua: the decoration of the city’s Capella Maggiore. Alongside the self-portrait at Dulwich are intimate depictions of his two wives, the first from c 1626 painted soon after the death, probably from bubonic plague, of Isabella Brant. This shows his ability to make an absent person ‘come alive.’ In pictures of his second wife, Helena Fourment, who was 39 years younger than Rubens and his muse and model of buxom proportions, one is aware of “the artist’s eye when he looks at the woman he loves.”

In addition to their affection for him, Rubens had extra reason to be grateful to both his wives, who had contacts in Antwerp high society and were noted for their fashion sense. A small painting

The Virgin in Adoration before the Christ Child (c 1616-1619) from Snijders & Rockox House, Antwerp refers to the marital bliss of Rubens. Presumably, Isabella Brant was the model, and in the Christ Child are the facial features of Nicolaas, his second son.

Most touching perhaps is the intimate portrait (c 1620-3) in oils of his daughter Clara Serena, and which is on long-term loan to the gallery from a private collection for an initial three years. This depicts Clara Serena, the first child of Rubens and Isabella, shortly before she died in 1623, just before her 13th birthday. He had painted her more than once. Clara Serena’s charming name symbolises sparkling brightness and tranquillity.

Rubens infused images of biblical women with affection and gravitas, reflecting his Roman Catholic faith. In the religious commissions we see immediate family members including his two wives and children, who acted as models.

After close encounters in the gallery with the women dearest to him, attention immediately switches to portraits of elegant, wealthy, and powerful women, some in sumptuous costumes. Rubens realised that his extraordinary ability to paint likenesses could open doors. At a time when his homeland was ravaged by the Eighty Years’ War (1568-1648) Rubens’s depictions of potentially peace-making women was no surprise. His dazzling and innovative portraits of them revolutionised the genre and reinforced his relationships with such patrons.

Dominating the first room is a luxuriant representation (courtesy of the Bankes Collection of the National Trust Collections, Kingston Lacy) of Marchesa Maria Serra Pallavicino, commanding in her resplendent garments — opulent silvery-silk gown, its train falling in substantial folds to the left, the gown overlaid with gold embroidered lace, all of which displays the painter’s technical brilliance in rendering textiles. She has a parrot near her shoulder which one might guess symbolised wisdom and intelligence. The architectural setting of the oil on canvas portrait, and the sitter’s opulent outfit and fan underline the status of the family. The portrait may have been made to settle a debt. A Latin inscription on the column records: Peter Paul Rubens has painted [this] and offered [it] as a gift with singular devotion in 1606. His employer, the Duke of Mantua, was frequently in debt to Genoa’s Pallavicino banking family.

Rubens’s portraiture coups went right to the top: his sitters included Archduchess Isabella (1566–1633), the daughter of King Philip II of Spain. She was married to Archduke Albert and alongside him ruled as sovereign of the Spanish Netherlands. After Albert died in 1621, she was made governor of the Netherlands representing the King. Isabella entrusted Rubens, her court painter, with not only artistic projects but also sensitive diplomatic missions. She had been unsuccessfully proposed by her father as the Catholic heir to the throne of England after the execution (1587) of Mary, Queen of Scots, and as a claimant through her mother to the throne of France after the murder of her uncle, Henry III (1589).

Marie de‘ Medicis, widow of Henry IV and regent queen of France, is another dramatic presence. She was so keen to have on record her status and authority that she commissioned in 1622 a series of 24 monumental paintings on her life and that of her husband. The series is today in the Louvre’s Galerie Médicis which recreates the splendour – which she knew from the Florentine palaces of her childhood – she had on display in the Luxembourg palace in Paris when she returned from exile forced on her by her son, Louis XIII. Rubens met the demand to paint the complete series in four years flat, singlehandedly. There were 21 canvases each 4 metres high, and three large portraits of the queen and her parents.

In Portrait of a Lady, Rubens delights in the woman’s deep purple silks, intricate lace, ribboned sleeves, and jewels, although her cuffs and right hand are sketchily shown, perhaps unfinished. Her identity is disputed. A chalk study for the painting bears an inscription identifying her as Katherine Manners, Duchess of Buckingham (1603-1649), whose husband, George Villiers (1592-1628), the Duke, met Rubens in Paris in 1625 and commissioned several pictures including portraits of himself and his wife, who never left England and therefore did not sit for the painting.

A separate mystery surrounds Portrait of a Woman (c 1625) painted in oil on panel, from the Royal Collection Trust, which shows the sitter wearing a gold-coloured robe with lace collars and cuffs; she could be Helena Fourment but more likely her sister, Elizabeth.

Rubens was born in Siegen, northwest Germany, after his father became the legal adviser to Anna of Saxony, the second wife of William I of Orange. Two years after his father’s death, Rubens moved with his mother to Antwerp, where he received a humanist education, studying Latin and classical literature. In May 1600, at the age of 22, he left Antwerp for Italy, where he stayed until 1608, employed by Vincenzo I Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua. He readily took up opportunities to travel to Venice, Florence, Rome, Genoa, and Spain.

From before 1600, he had been engrossed by ancient sculpture, fascinated by antique marble and by the stories of Ovid and Virgil. In Italy, he studied statuary, memorising forms and postures. He also drew on Michelangelo, who was similarly informed by ancient art. This fed into the mythological narratives that he loved to paint, inspired by the Renaissance paintings of Titian, where the goddesses Venus, Juno and Diana are presented as strong and intelligent.

The female nude was a subject in constant evolution in Rubens’s art. At the time, nudes were sometimes illustrated from male models, who were more readily available than women models, and for reasons of propriety. Rubens’s early nudes were different in style from those for which he became famous, a result of his involvement with sculpture, although Rubens remarked that paintings should not “smell of stone.” Recording observations in his notebook, Rubens devised a new type of vigorous, monumental, female nude.

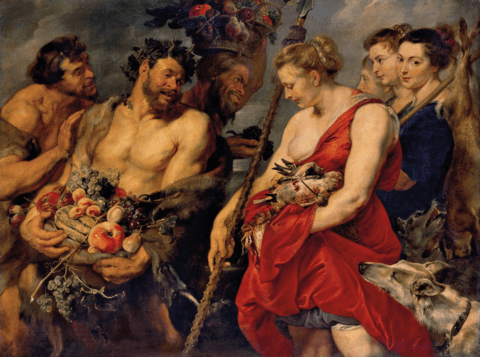

A blockbuster finale to the show includes large-scale paintings of heroic mythological women including The Birth of the Milky Way (1636-1638) from the Museo del Prado, Madrid, on display in the UK for the first time; Diana Returning from the Hunt (c 1615), an idyllic scene celebrating abundance, the daily rejuvenation of nature, and the sensuality of female beauty; and Dulwich’s Venus, Mars and Cupid (c 1614).

In another Dulwich picture, Three Nymphs with a Cornucopia (c1625-1628) in oil on oak panel, Ceres, goddess of abundance, is shown holding a horn of plenty overflowing with the fruits of the earth. This has been described as much a study of Rubens’s ideal of female beauty as it is an allegory of fruitfulness and plenty. It is a modello (oil sketch) made in preparation for a large canvas, on display nearby. The finished version was one of eight pictures that Rubens presented to Philip IV of Spain (1605-1665) on the monarch’s arrival in Madrid in 1628.

Underlining Rubens’s fascination with the classical world, the exhibition includes Crouching Venus (200 AD), a marble statue of Aphrodite dating from the second century AD, which is a Roman version of a Hellenistic original from 200 BC. The statue is from the British Museum where it is on long-term loan from the Royal Collection Trust.

The exhibition was developed in close relationship with the Rubenshuis in Antwerp and curated by Dr Ben van Beneden (former director of the Rubenshuis and co-author of the Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard) and Dr Orrock, an independent art historian.

Jennifer Scott, director of Dulwich Picture Gallery, said: “It is a show we absolutely had to do. At Dulwich Picture Gallery we have a superb collection of pictures by Rubens.” The exhibition presented heroines based on inspirational women in the artist’s life, and “this is an exciting opportunity for audiences to reconnect with one of art history’s most famous figures.”

Dr Orrock spoke of “the many faces of Rubens’s women, all depicted with his mix of skill, erudition and humanity.” Dr van Beneden said: “This exhibition… will encourage visitors … to look beyond certain clichés. If Raphael endowed his female figures with grace, and Titian with beauty, Rubens gave them veracity, energy, and soul.”

A series of responses to the exhibition is relayed on the Bloomberg Connects app. Among them, contemporary artist Claire Partington, who sculpts figures based on portraits of Jacobean society “in their fantastical symbolic costume” said: “I think art history is a real insight into fashion history and the sort of dynamics of how people want to present themselves and the language of objects, but also the language of poses… to me that directly relates to an Instagram selfie and how people want to present themselves with their possessions now.”

Captions with detail:

Clara Serena Rubens, The Artist’s Daughter, c 1620-3, oil on panel. Private Collection.

Peter Paul Rubens. Private collection, Antwerp; and his first wife Isabella Brant c 1626 c. Oil on canvas. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

The Virgin in Adoration before the Christ Child, c 1616-1619. Oil on panel. KBC Bank, Antwerp, Museum Snyders & Rockox House.

Portrait of a Lady c 1625. Oil on panel. Courtesy Dulwich Picture Gallery.

Marchesa Maria Sierra Pallavicino, 1606. Oil on canvas. Kingston Lacy, The Bankes Collection (National Trust).

Diana Returning from the Hunt, c 1623. Oil on canvas. By Peter Paul Rubens and Frans Snyders. Courtesy bpk/ Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden/Elke Estel/Hans-Peter Klut.

Three Nymphs with a Cornucopia, c1625–1628. Oil on panel. Dulwich Picture Gallery.

Rubens & Women is at Dulwich Picture Gallery until January 28, 2024