Tate Modern celebrates pioneers of Expressionism: Kandinsky, Münter, and the Blue Rider group

By James Brewer

Sporting a distinctive crimson hat, she stares out directly, her irises a startling hue somewhere between red and orange. Marianne von Werefkin’s self-portrait from around 1910, the year of her 50th birthday, is a statement of her magnificent individuality and independence. She was a leader of an art movement that was far from being a ‘boys’ club’ as most such had been a few years previously. Better known today are two others in that unorthodox movement, Wassily Kandinsky and his partner Gabriele Münter, and it is only right that Werefkin is being accorded measured prominence in an important new exhibition in London.

Just as the empowered woman of today seeks to stamp her personality on wider society, Russian-born Marianne was set on taking charge of her self-image. Flamboyant accoutrements and make-up were part of her bohemian ways and aligned with her influence on the milieu in which she moved. Glowing in her fiery eyes is the blaze of colour akin to her resolute brushstrokes on the canvas. Her lively intellectual salon in Munich was the springboard for the rise to fame of some of the best-known painters of the Expressionist genre.

Tate Modern has unveiled a fascinating tableau of their evolution under the title Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider. This draws on the world’s richest collection of expressionist masterpieces, which is held by the Lenbachhaus in Munich, along with rare loans from public and private collections, including 50 works seen in the UK for the first time.

Gabriele Münter painted a Portrait of Marianne von Werefkin while living with several of the group in Murnau, a small Bavarian town by the shores of the Staffelsee in the foothills of the Alps. Gabriele put it this way: “I painted the Werefkina in 1909 in front of the yellow basement of my house. She was a woman of grand appearance, self-confident, commanding, extravagantly dressed, with a hat as big as a wagon wheel, on which there was room for all sorts of things.”

Under the curious name The Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter) coalesced a diverse group who were to transform modern art in terms of colour, light, sound, and performance. Led by Kandinsky (1866-1944) and Franz Marc (1880-1916), their enthusiasm for abstract and naïve forms and prismatic colours meshed with their spiritual ideas and disenchantment with the materialism and venality of the day. Munich where many cultures and social mores intersected was their ideal base for experimentation.

For Kandinsky, the horse with rider was a symbol for reaching beyond realism. Horses were metaphors of power, freedom and pleasure. Marc adored horses and his many primitivist paintings of these and other animals evinced a return to nature and rebirth. Both artists were fascinated by the colour blue, allusive to ocean and sky, and they invested it with mystical significance. Kandinsky had given up an academic law career in Russia to move to Munich. The exhibition credits his development of abstraction in part to the innovation and angularity inherent in his woodcuts.

The three portraits shown at the Tate of Marianne Werefkin (1870 -1938) transmit an engrossing, almost mesmerising, conspectus of the animating principles of the group around her. Endowed with a private income, she cultivated an avant-garde atmosphere among the varied nationalities, communicating with them in Russian, German, English, French, Polish, Lithuanian, and Italian. Poets, dancers and avant-garde figures including Sergei Diaghilev were welcomed in her home.

In the 1880s, she had studied with the great Russian artist Ilya Repin, who compared her to Rembrandt and was convinced she could become a great realist painter; but in 1892 she fell in love with another Repin student, Alexei Jawlensky. Four years later, the couple moved to Munich, where with like-minded souls she eagerly discussed the latest styles and techniques gleaned from books and magazines. She travelled widely in Europe studying modern and Renaissance painting. Her motto was: “Art is the spark caused by the friction between an individual and life.”

Marianne’s self-portrait from around 1910, in tempera on paper on card, although of modest size is a statement of her bold, energetic personality. Her strong facial features are emphasised and there is a sensuality associated with masculinity. She confronted gender stereotypes: on a nearby gallery wall is her provocative 1909 portrait of Alexander Sacharoff, capturing the fluidity of his movements as a free-style performance artist and dancer. Sacharoff’s energy and intensity was also a subject for Jawlensky’s brush.

Around the same time, Erma Bossi (1875-1952) who was born near Trieste, and met Kandinsky and Munter after moving to Munich, was clearly also captivated by Marianne and painted her in a more relaxed but still supremely self-assured pose. Bossi’s busy Circus including clowns and a performer balancing on one leg on a white horse is a kaleidoscope of movement.

Members of the circle spent the summer of 1909 in Murnau, and their encounters with the local landscape and culture reinforced a move to expressive line and colour, leading Kandinsky and Münter to radically new approaches in both abstract and figurative painting such as the 1909 portrait of Marianne.

Their friends and collaborators Franck-Marc and his wife Maria Franz-Marck explored the animal world and the creativity of children through works such as, respectively Tiger 1912 and Girl with Toddler c 1913.

Modernism was fascinated with sound, colour and light. Many of the Blue Rider circle were accomplished or professionally trained musicians. Kandinsky was a skilled cellist. Paul Klee (1879-1940) and Lyonel Feininger (1871-1956) who was a noted caricaturist and who created woodcuts and paintings of ships at sea, were gifted violinists.

Kandinsky’s striking abstract Impression III (Concert) 1911 underlined his interest in the connections between colour and sound. The painting was a chromatic response to the atonal compositions he listened to during an Arnold Schönberg concert he and Marc attended in Munich in January 1911. It is one of a series of six Impressions springing from what Kandinsky wrote to the composer: “The particular destinies, the autonomous paths, the very lives of individual voices in your compositions are precisely what I have been looking for in pictorial form.” It was a follow-up too to Goethe’s work on the psychological impact of different colours on mood and emotion, published as Theory of Colours in 1810. The Blue Rider artists pursued these theories through experimentation such as shown in was Marc’s 1911 painting Deer in the Snow II.

In 1912 leaders of the group put a good deal of work into compiling their Almanac, edited by Kandinsky and Marc, declaring that “the whole work, called art, knows no borders or nations, only humanity.” Schönberg’s contribution to the Almanac alongside those of the composers Thomas von Hartmann and Leonid Sabaneev were central to the group’s questioning of the boundaries between creative mediums.

The exhibition records how the pioneering Expressionists left an indelible legacy by publishing manifestos and editorials, curating exhibitions, putting on shows, and fostering relationships with museums and galleries. Münter staged a solo show under the auspices of Berlin’s cultural and arts magazine Der Sturm.

The outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 figuratively blew the unity of the collective sky high, but its achievements and aspirations for a transnational creative community live on. Kandinsky, as a Russian citizen, was expelled from Germany to return to his homeland. Marianne and Jawlensky moved to Switzerland, where their relationship ended in 1921. Tragically Marc and another Blaue Reiter artist, August Macke, were killed in action. Only 27 years old, Macke had already had a considerable impact in his field.

Following the Russian Revolution, Kandinsky joined the administration of culture commissar Anatoly Lunacharsky, but amid disagreements returned to Germany in 1920 and his style became increasingly geometric. He taught at the Bauhaus school of art and architecture from 1922 until the Nazis closed it in 1933, when he moved to France, where he lived for the rest of his life,

Klee, dismissed from his post as a professor of the Art Academy in Düsseldorf, went back to his native Switzerland. His 1919 painting Swamp Legend in which the human figure was blended in abstract yellow and violet was among those condemned as degenerate art in 1937. Klee produced an estimated 10,000 works of art.

After the Nazis took power, Gabriele hid dozens of paintings by Kandinsky and others in the basement of her home. Shortly before her death, she donated these, 1,000 in all, to the Lenbachhaus collection. As part of the current collaboration, Tate lent 80 works from its Turner Bequest to enable the Lenbachhaus to put on the first solo Turner exhibition in Munich.

Investors in the art market always have their eyes on the Expressionists. Murnau mit Kirche II (Murnau with Church II), a 1910 painting by Kandinsky that once belonged to victims of the Holocaust sold in March 2023 at Sotheby’s in London for £37.2m ($45m), an auction record for the artist. A previous record for a work by Kandinsky was set in 2017 by the sale of his Bild mit weissen Linien for £33m ($39.7m). For Münter, the record price at auction is $2.37m, and for Franz Marc, $56.8m. For Werefkin, the record is surprisingly much lower, $663,000.

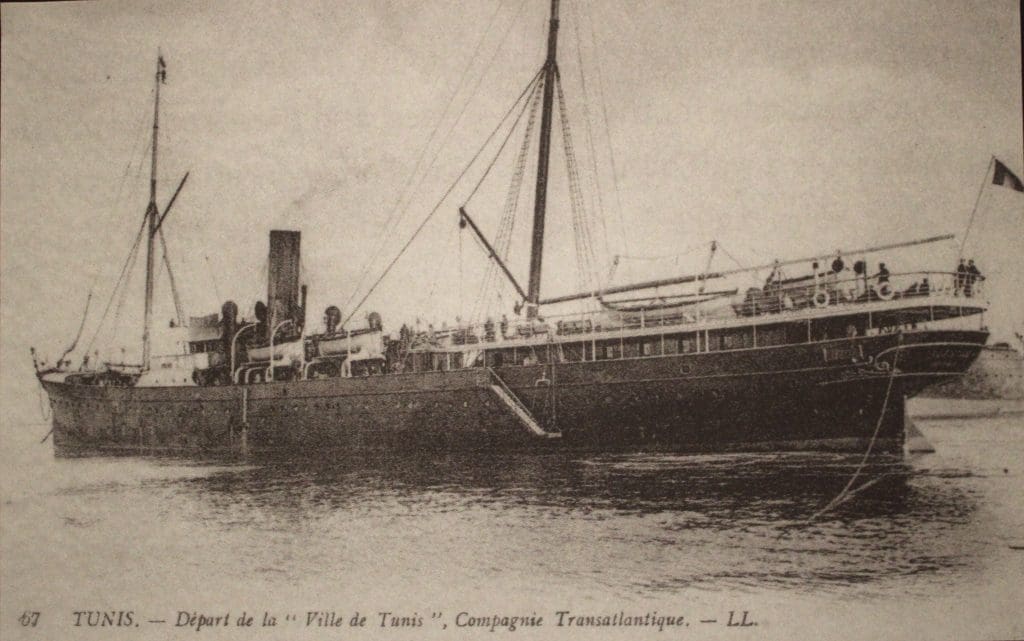

From her 20s, Münter was a keen photographer. Pictures taken with her box camera show a lively interest in reportage of everyday life in North Africa, and what she saw on her travels in the US. The exhibition includes a postcard of the Ville de Tunis, the Compagnie Transatlantique steamship on which Munter and Kandinsky travelled from Marseilles to the Tunisian port of Bizerte.

Expressionists is presented in Tate’s Eyal Ofer Galleries and is supported by the London-based grant-donating Huo Family Foundation which sponsors projects in the UK, US and China. The exhibition is organised by Tate Modern in collaboration with Lenbachhaus Munich. It is meticulously and lovingly curated by Natalia Sidlina, curator of international art at Tate Modern and Genevieve Barton, assistant curator in the Tate Modern international art department.

Captions in detail:

Self-portrait I, c 1910. By Marianne Werefkin. Lenbachhaus, Munich.

Portrait of Marianne Werefkin, c 1911. Oil paint on card. By Erma Bossi. Lenbachhaus, Munich, on permanent loan from The Gabriele Munter and Johanes Eichner Foundation, Munich.

Portrait of Marianne von Werefkin, 1909. By Gabriele Münter. Lenbachhaus Munich, Donation of Gabriele Münter, 1957 © DACS 2023.

The Dancer, Alexander Sacharoff, 1909. By Marianne Werefkin. Tempera on paper on card. Fondazione Marianne Werefkin, Museo Communale d’Arte Moderna, Ascona.

Tiger, 1912. By Franz Marc. Lenbachhaus Munich, donation of the Bernhard and Elly Koehler Foundation 1965.

Impression III (Concert), 1911. By Wassily Kandinsky. Lenbachhaus, Munich, donation of Gabriele Münter, 1957.

Der Blaue Reiter, R Piper & Co., Munich, 1912. Book cover. Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Postcard of the departure of the Ville de Tunis, c 1904, the Compagnie Transatlantique steamship on which Munter and Kandinsky travelled. DORA Collection, Sydney.

Promenade, 1913. By August Macke. Lenbachhaus, donation of Bernhard and Elly Koehler, 1965.

Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider continues until October 20, 2024, at Tate Modern, London.