By James Brewer

A captivating designer, painter, printmaker and embroiderer of the 1930s and 1940s, Tirzah Garwood (1908–1951) is at last justly hallowed by a London exhibition of the current age.

Tirzah’s talent, appealing personality and gentle humour shine bountifully through Dulwich Picture Gallery’s wonderful presentation entitled Tirzah Garwood: Beyond Ravilious. The title is explained by the fact that she has been largely unknown outside a narrow circle, and often referred to as “the wife of Eric Ravilious.” Eric having been a brilliant watercolourist and a war artis of planes, ships and coastal defences; his popularity endures this century through reproductions in fine art prints and greetings cards.

While sharing an intellectual sensibility with her husband, Tirzah emerges through this show as an inimitable individual. Remarkably, since a memorial exhibition after her death 73 years ago little has been publicly said about her.

Her unusual appellation was a pet name given by her family: Eileen Lucy Garwood was the third (tertia) child of an army colonel. Today’s art lovers will take great pleasure in learning of this versatile artist’s memorable accomplishments, scrupulously honoured in Dulwich’s retrospective, framed with love and respect, for it is the first time that the full extent of her output has been shown.

There are no blockbuster works, but everything is lucidly set out with a winsome charm.

We begin to get to know her and Eric in portraits from 1929 by Phyllis Dodd (1899-1995), who had studied with Eric at the Royal College of Art. Phyllis shows Tirzah stylishly dressed in loose-fitting blouse and V-neck sweater. Framed by the brim of a fashionable green cloche hat (coincidentally The Green Hat by an author named Michael Arlen was a popular, slightly risqué novel published in 1924), her features are calm, with her gaze unwavering.

Then there is a portrait of Tirzah with luxuriant brushed-back hair, looking out serenely. This is from later in life, after she had lost her husband in World War II and gone through an operation for cancer. The work from 1944 is by Duffy Ayers (1915–2017), a friend and neighbour who painted in the quiet realist tradition they both employed. Tirzah herself had at an early stage made a series of unconventional self-portraits, among them an embroidery from the 1930s showing her yawning in front of a sloping bedroom mirror.

Tirzah Garwood: Beyond Ravilious gives Tirzah’s beguiling output the attention and public showcase it warrants. Here are more than eighty of the deeply sensitive artist’s works, including most of her surviving oil paintings, with wood engravings, pencil sketches, collages and experimental marbled papers, almost all from private collections.

We recognise clear thematic similarities yet distinct artistic personalities of the gifted couple, as the exhibition helpfully includes 11 of Eric’s watercolours such as The Vicarage, 1935.

Though from different backgrounds – Tirzah wrote of his “unfamiliar and rather frightening working-class world” – the duo were alike in their moral outlook.

The exhibition unfurls the life of a woman who was strong in the face of adversity and presents what has been called her “sophisticated naïve” approach of infusing apparently innocent or straightforward subjects with deeper meaning and warmth.

A specially designed archway leading into the exhibition is modelled on a scene from Tirzah’s 1929 wood engraving The Crocodile, in which a file of smartly uniformed schoolgirls in the street passes by a curious dog.

Tirzah loved storytelling through her pictures, making box-shaped tableaux for her children, and unassumingly celebrating the joy of daily life. Her playful side, her lightness, and a sense of wonder were uppermost.

From their first meeting in 1926, when Tirzah began studying wood engraving with Eric at Eastbourne School of Art, their aesthetic and personal lives were enmeshed. Influence flowed both ways. While she learned the techniques of wood engraving from Eric, Tirzah encouraged him to explore day-to-day life and locations in his work.

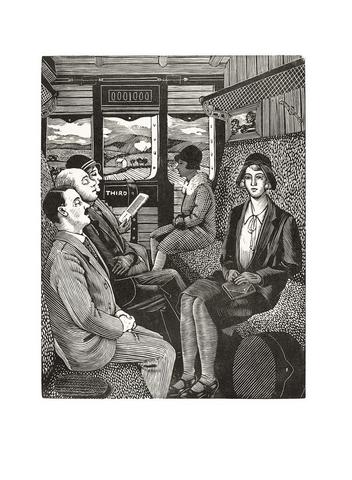

Having gained an understanding from Eric of how to convey surface textures, Tirzah became skilled in projecting the look and feel of different fabrics. In the wood engraving The Train Journey from 1929 she deftly emulates the three-dimensional aspect of a compartment and its seating material. In the picture two male passengers are in a reverie, oblivious to the scenery of chalk hills visible from the window, and a woman is reading. Facing us is Tirzah herself with her intent regard, wearing a stylish blouse and familiarly, a cloche hat.

When in a different picture she arrives for the day in London, her notional character is less confident. In Kensington High Street, she is overwhelmed by crowds of shoppers and seemingly, by the presence of her aunt. Women in winter coats and scarves bustle past shop-window mannequins modelling scanty summer fashions.

In the oil painting Etna, from 1944, with a tendency to dreaming she glories in mastering perspective. Through the chalk landscape of the East Sussex hill Mount Caburn trundles a toy train, named of all things, Etna. Hens and barley compete for attention in the foreground. Her viewpoint is the garden of a cottage rented by her friend Peggy Angus (1904-93), a noted designer of tiles and wallpaper.

Tirzah had great success when she turned to producing hand-marbled papers, which were ordered in batches of 50 and more by book publishers, by shops making curved designs for lampshades, and by private clients. Marbling is a refinement of an ancient tradition by Persian, Turkish and other calligraphers who made ornate papers for binding, mounting, and margining manuscripts, and embellishing stationery.

Her interest in the technique started while she and her husband were sharing a home named Brick House at Great Bardfield near Braintree in Essex with Edward Bawden (1903-89), a printmaker, illustrator, watercolourist and designer, and his wife Charlotte, a ceramicist and painter. Edward did commercial work for companies such as Twinings the tea specialists and Fortnum & Mason and made linocuts depicting everyday England. He apparently tried marbling, before turning his attention to other interests because he found it time-consuming and tricky. Having begun making marbled papers with Charlotte in 1934, Tirzah seized on the potential and developed her own approach, layering delicate patterns into harmonious designs said to be unlike anything being made in Europe.

To create her papers, Tirzah dropped thinned oil paint into a bath of water thickened with gum tragacanth (a substance obtained from tree sap) and let the spots expand into a circle or drew the paint with a needle into a feathered shape. A sheet of paper laid over the designs would take up the coloured pattern. A close look at the patterned papers in the Dulwich exhibition shows how the layering achieves its affect.

“Marbling gave me pleasure because I thought no-one else could do this,” said Tirzah. It also made a valuable contribution to household income. All the time, she was juggling her creative practice with the demands of motherhood. Some of her marbled pieces are held by museums, but the works displayed in the new exhibition are from private collections, many exhibited for the first time.

After marrying in 1930, Eric and Tirzah lived in Hammersmith before joining Edward and Charlotte Bawden, and their home Brick House became the centre of a community of artists. The Ravilious couple moved in 1934 to Castle Hedingham near the border with Suffolk, and later to Shalford, south of Guildford.

For Tirzah, 1942 was a tragic year, with first an emergency mastectomy for breast cancer, and then losing her husband, who became in September 1942 the first British war artist to die on active service in World War II when his aircraft was lost off Iceland. After all that, one would have thought her inner self would have gone into some sort of retreat. Instead, her spirit was nourished by the joy of having young children around.

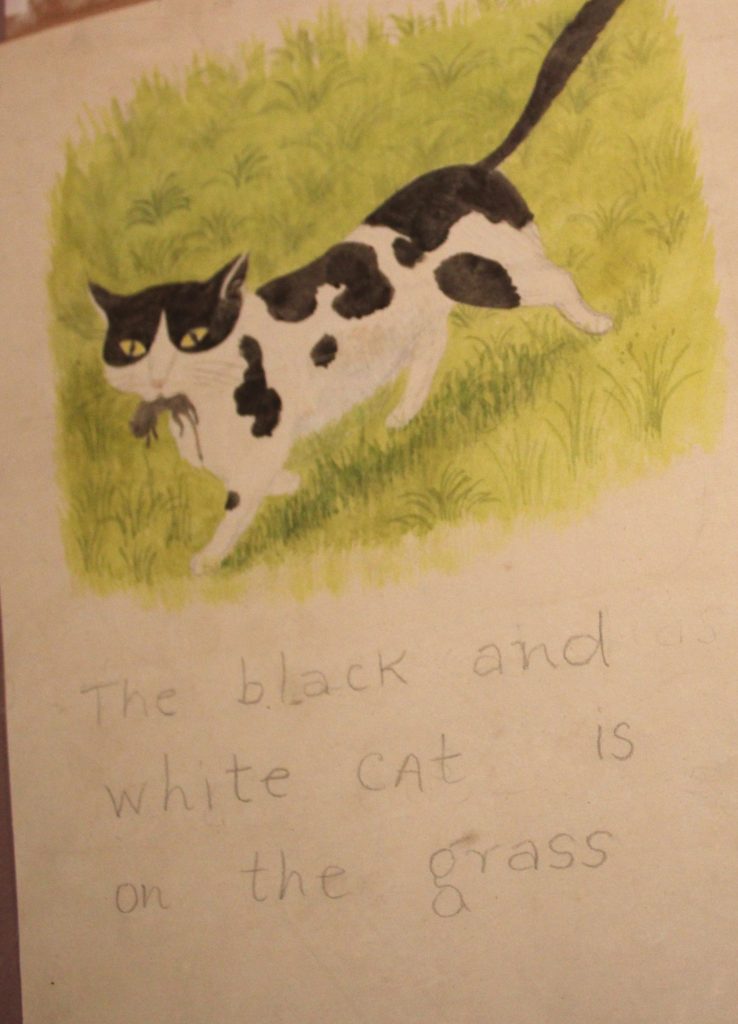

She wrote her autobiography Long Live Great Bardfield and returned to oil painting and other media. The exhibition includes her tender-hearted sketches, which depict her children John, James, and Anne, and her artworks set in modelled box frames. With delights such as Two sisters, done in 1944 in coloured pencil on paper, and from the same year an unfinished watercolour The black and white cat is on the grass, one can almost sense the artist caressing her children and the pet in the garden.

She married BBC producer Henry Swanzy in 1946, and she described her final year, spent in a nursing home, perhaps surprisingly as the happiest of her life. She was painting like she had never painted before. She made models of local schools, cottages and chapels from cardboard and paper. Taking inspiration from the countryside she had always loved, fascinated by the flowers and insects, and from illustrated Victorian children’s books, she made dreamlike paintings such as Hornet with Wild Roses. These works fill the last room of the gallery, a fitting tribute to the irrepressible artist.

The exhibition is adroitly curated by James Russell (who previously curated ‘Ravilious’in2015, and ‘Edward Bawden’in2018). The Bawden exhibition brought together 160 works to re-introduce the breadth of his output over his 60-year career.

James Russell said: “Tirzah Garwood found her subjects in the everyday world around her, from members of her family to pets, insects, toys and buildings. Whatever her clear gaze rested on, her playful imagination and skill in technique and composition transformed into something strange, magical and utterly captivating. She displayed her sense of humour and sense of humanity in everything she did. Curating this exhibition has been like opening a box of treasures.”

Jennifer Scott, director of the gallery, added: “Audiences will be able to discover this accomplished, visionary artist who has been overlooked for too long.”

No longer out of sight, Tirzah Garwood with her distinctive and engaging persona is grandly celebrated by Dulwich Picture Gallery. A full-colour catalogue features new research, and essays by Ella Ravilious (granddaughter of Eric and Tirzah) and Jennifer Higgie, an author, editor and art critic.

Images

Exhibition entrance, modelled on the artist’s 1929 wood engraving The Crocodile. Private collection. Fleece Press.

The Train Journey, 1929. By Tirzah Garwood. Wood engraving. Private collection.

Portraits of Tirzah Garwood and Eric Ravilious, 1929. By Phyllis Dodd (1899—1995). Oil on canvas. Private collection.

Portrait of Tirzah Garwood, 1944. By Duffy Ayers. Oil on canvas. Private collection.

Etna, 1944. By Tirzah Garwood. Oil on board. Image courtesy of Fleece Press /Simon Lawrence.

Hornet and Wild Rose, 1950. ByTirzah Garwood. Oil on canvas. Towner Art Gallery, Eastbourne (Image courtesy of Fleece Press/Simon Lawrence).

Marbled papers. By Tirzah Garwood. Private collection.

Yawning, c 1930s. By Tirzah Garwood. Embroidery. Private collection.

The black and white cat is on the grass, c 1944-45. By Tirzah Garwood. Watercolour.

Two sisters, c 1944. By Tirzah Garwood. Coloured pencil on paper. Private collection.

The Vicarage, 1935. By Eric Ravilious. Private collection.

Tirzah Garwood: Beyond Ravilious is at Dulwich Picture Gallery until May 26, 2025.