By James Brewer

The National Gallery chose the title Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers. It could well have added the words “… and Olive Trees,” because the artist’s reverence for those sun-loving symbols of fruitfulness enriches the gallery’s superlative exhibition.

Choreographing the plantations in vibrant colours was one of the signal attainments of Vincent’s two years from 1888 spent in the South of France from where he journeyed, troubled, to a village near Paris where he took his own life.

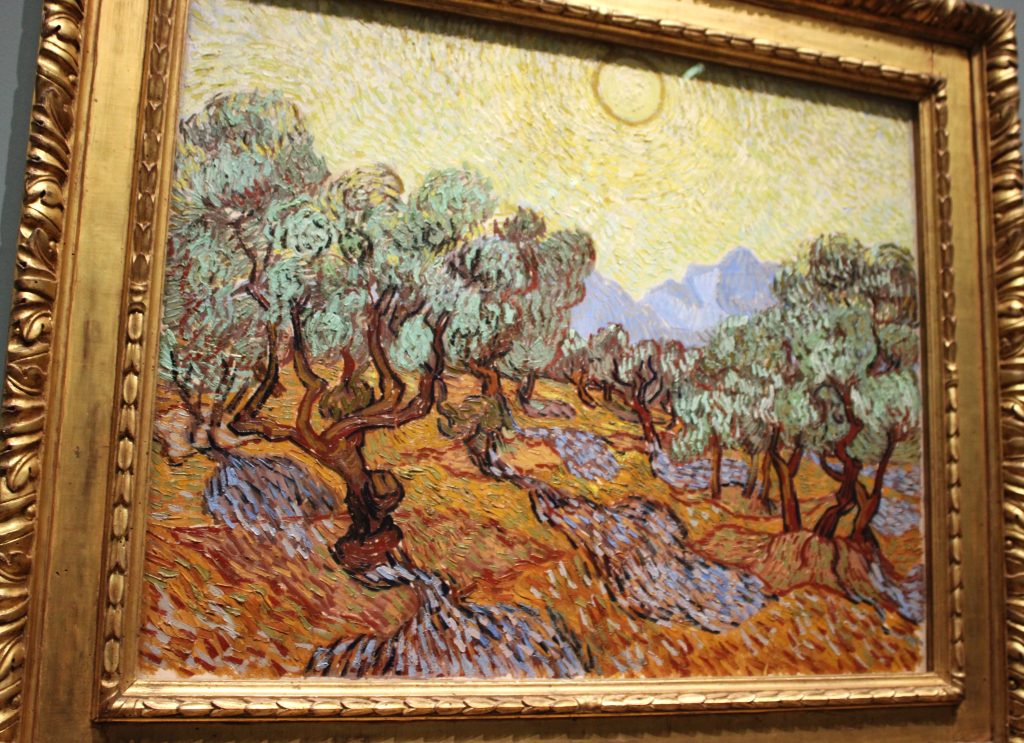

To understand his communion with nature, read one of his descriptions of the distinctive glow he visualised emanating from the olive trees which he saw as “very characteristic and I’m struggling to capture that. It’s silver, and sometimes more blue, sometimes greenish, bronzed, whitening on ground that is yellow, pink, purplish or orangish to dull red ochre.” This awe-struck homage is from a frequent and frank correspondence with his brother Theo, fortunately imparting in detail how that great revolutionary style matured. Clarity of mind and clarity of purpose in artistic endeavour from a man whose mental health has been a topic of endless speculation.

From his impassioned words we have no doubt that the trees with their seemingly writhing trunks were a staple in his poetic dreaming alongside his search for religious epiphany through the vision of the stars. Although not as headline-making as his starry skies and swirling clouds and simple bedside chair, his treatment in rapid, dramatic strokes of curving leaves (as if they were audibly swishing in the breeze), gnarled trunks and with cypress trees overshadowing shimmering and often scrabbled ground, is stunning.

Poets, writers and artists, real and idealised, were a terrain of immediate and intense appeal to Vincent. We are welcomed into his surroundings in Arles and Saint-Rémy which fired his determined outflow of canvas after canvas. Working rapidly – sometimes completing a painting in just one session – and confident that he was forging new ground, Vincent during his short life poured forth around 2,100 artworks, including close to 900 oil paintings.

As well as celebrating the Gallery’s 200th anniversary, Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers marks the centenary of the Gallery’s acquisition of Sunflowers and of Van Gogh’s Chair. The institution owns other major paintings made towards the close of his career: Wheatfield with Cypresses (1889) acquired in 1923, and Long Grass with Butterflies (1890), which entered the collection in 1926.

This first major exhibition of the artist’s work staged by the Gallery includes masterpieces from collections near and far, such as Starry Night over the Rhône, self-portraits and The Yellow House, and sheds light on his pen and ink drawings of landscapes. Peerless pictures are loaned by among others the Kröller Müller Museum in rural Netherlands, the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, the Athens-based Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation, and from east and west coasts of the United States. Some of the exhibits have seldom been seen in public, and all 50-plus works are in a pristine state of preservation.

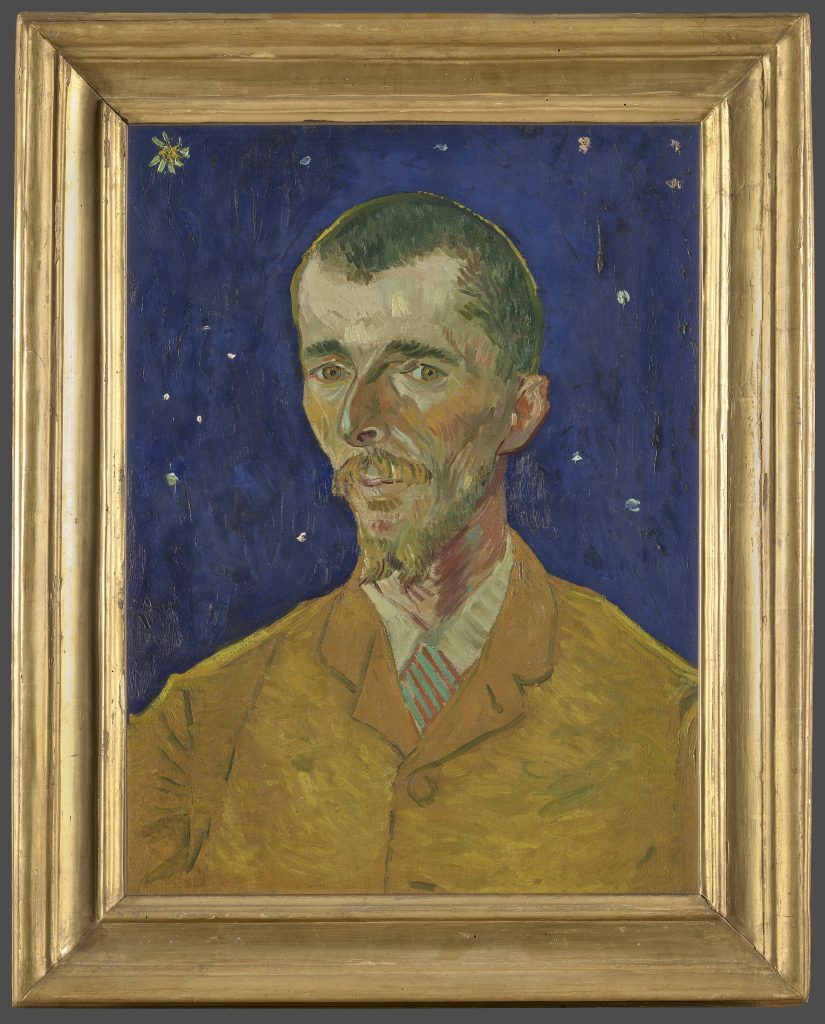

Reading novels and poetry by authors including Zola, Flaubert, Dickens, and George Eliot unleashed his imagination, feeding his concept of turning familiar places into arenas of fantasy. One of the portraits painted to decorate the Yellow House, in which he rented rooms and hoped would become a base for a cluster of star artists from Paris, was of Eugène Boch, a 33-year-old Belgian Impressionist. Boch’s gaunt face made Vincent think of Dante. Shown head and shoulders against a starry night sky, the stereotypical ‘poet’ stands here before the wide blue yonder.

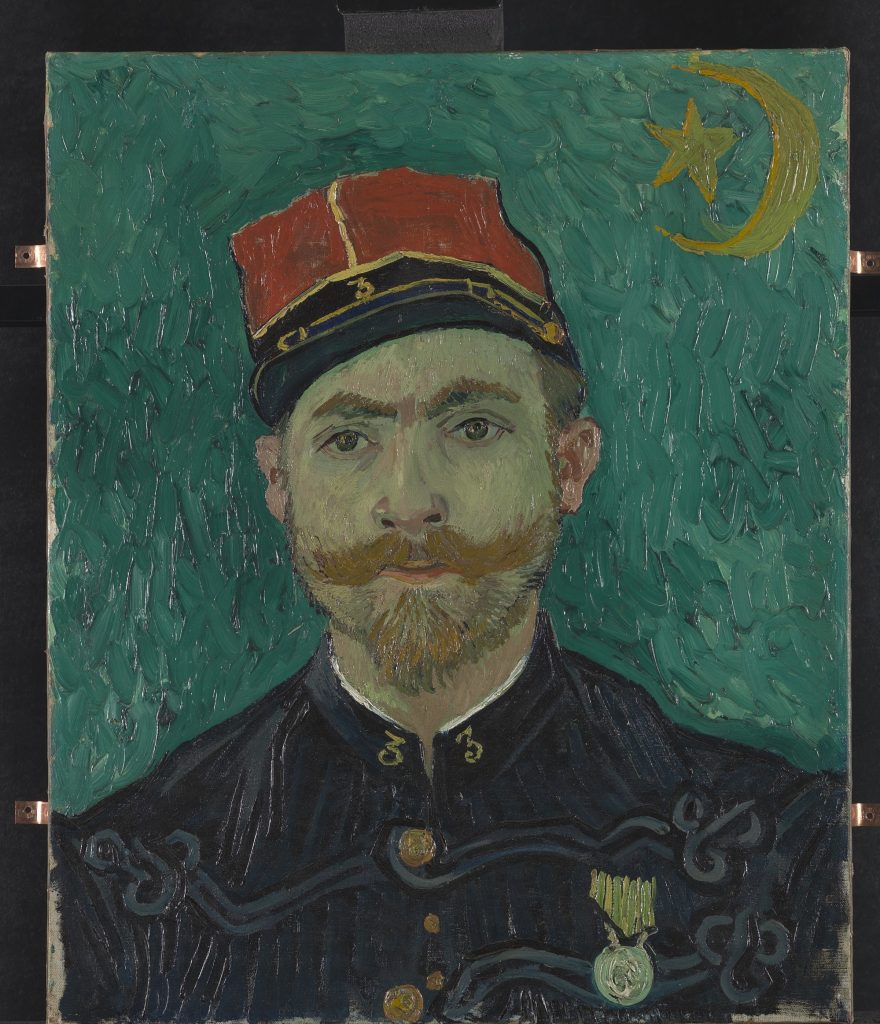

The Lover is typified by the assured Paul-Eugène Milliet, a second lieutenant in the French army, spruce in his uniform with jaunty kepi, handlebar moustache and penetrating eyes, set against a verdant background showing the symbol of his regiment, the crescent moon and star. “He looks a bit seedy,” whispered a lady visitor to a companion as they walked past his portrait in the gallery.

The fanciful Van Gogh pronounced the conventional public park across from the Yellow House to be the Poet’s Garden, visualising the Renaissance figures Dante. Petrarch and Boccaccio strolling among the bushes on the flowery grass. He planned to decorate the Yellow House with his pictures on the themes of the Poet’s Garden, the Sunflowers and the Poet and the Lover.

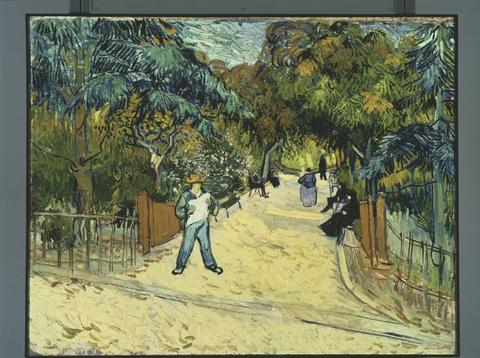

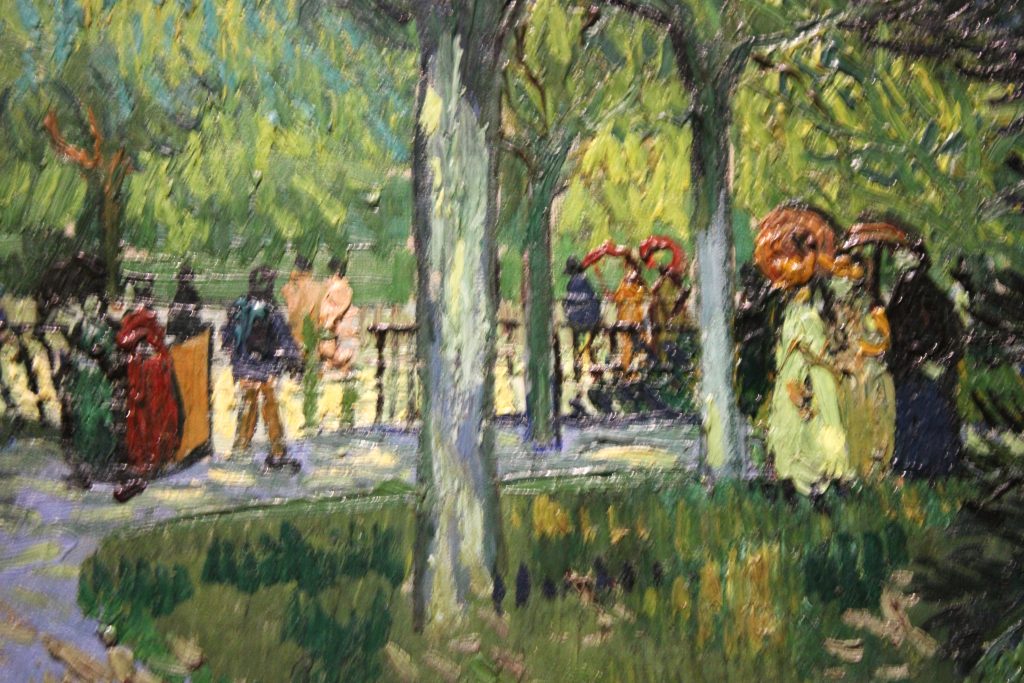

Thanks to this exhibition, there is a golden opportunity to stand close and “enter the park,” observing detail that might be overlooked at first glance – such as small groups of people in The Public Garden, Arles, and in Path in the Park, Arles.

He made four paintings stemming from his preoccupation with this Eden of The Public Garden at Arles, and in one of them, two indistinctly defined lovers walk hand in hand beneath a luxuriant blue fir tree. In another representation of the park, even the small-scale seated, spectating figures breathe life.

In The Path in the Park, Arle, the foliage again overwhelms groups of figures scarcely delineated. In May and June of 1889, after Van Gogh was admitted to hospital in Saint-Rémy, he imagined that building’s overgrown garden too as a secluded rendezvous for lovers.

Vincent told his brother that olive and cypress trees had rarely been painted and he set to work adapting his finely grained brushwork to energetic texturing. The theme surely reflects his immersion in Christian stories including the Bible narrative that Jesus was seized in a garden of olives before being tried and crucified. Although the son of a Dutch Reformed Church minister and having sought to become a lay minister himself, Vincent wanted to show his painter friends Paul Gauguin and Émile Bernard that art with spiritual significance without overtly religious motifs.

Lent by the Minneapolis Institute of Art, The Olive Trees has a prominent, intensely yellow sun – a source of life itself – churning the whole sky and hovering above a grove of sinewy trees populating the seething, red earth.

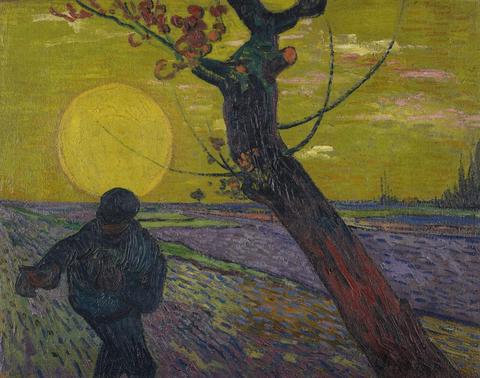

This device of the sun as the pulse of existence echoes what we see with The Sower in which the disc of the sun becomes a halo glorifying the hard graft of the farmhand. Conscious of the symbolism of sowing and reaping, the poet of the stars was equally soil-bound.

Vincent revelled in the challenge of painting by night. In a letter to his sister, Wilhelmina, he wrote that he wanted to paint night without black: “Now I absolutely want to paint a starry sky. Often it seems to me that the night is even more richly coloured than the day, coloured with the most intense purples, blues and greens. When you look closely, you’ll see that some stars are lemony, others have pink, green, blue or forget-me-not lights. And without insisting any further, it is obvious that to paint a starry sky it is not at all enough to put white dots on blue black.”

The hypnotic Starry Night Over the Rhône was painted by the river, just a few minutes’ walk from the Yellow House. It depicts the view looking south towards the town centre, peppered by the recently installed street gaslights. This allowed him to capture assiduously the wavy reflections from the lamps across the fast-flowing river. In the foreground, on the bank, are two strolling lovers, and boats that are moored. The silhouettes of roofs and bell towers stand out against the sky.

He arranged the non-terrestrial features according to his astronomic observations, and as a portent of the destiny of humankind. “On the aquamarine field of the sky the Great Bear [also known as Ursa Major] is a sparkling green and pink, whose discreet paleness contrasts with the brutal gold of the gas,” he described the work to Theo. Vincent exhibited Starry Night over the Rhône and Sunflowers at the Salon des Indépendants in September 1889, finding that people liked his oeuvre; as often happened though, this did not translate into sales.

The picture was the relatively placid predecessor of what would become an even more celebrated celestial painting, entitled simply The Starry Night, now in New York’s Museum of Modern Art. In the later picture, much of the contents of which is a figment of his imagination, the pullulating stars and crescent moon illuminate a village and, in the foreground, looms a huge Provençal cypress.

The National Gallery presents a double treat — TWO Sunflowers paintings, having borrowed one from the US to complement its own. The second was acquired by the Philadelphia Museum of Art from an American painter and art collector in 1935. The two are thus seen together for the first time since early 1889 when they were in Vincent’s studio. This has offered the opportunity to realise one of Vincent’s ideas for a decorative arrangement. In that, the two ‘Sunflowers’ are displayed flanking La Berceuse (1889), which is Vincent’s portrait of Augustine Roulin, wife of his friend the postmaster of Arles. The rope in her hands suggests that it is tied to a cradle which the viewer does not see. La Berceuse is on loan from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

In Vincent’s mind, what the picture of Mme Roulin stood for was self-evident. Writing to his brother, Vincent idealised it as being “in the cabin of a boat” where fishermen in “their melancholy isolation, exposed to all the dangers, alone on the sad sea… would experience a feeling of being rocked, reminding them of their own lullabies.”

The Philadelphia Sunflowers had been left with friends of Vincent in Arles. The London Sunflowers was sent to Van Gogh’s brother Theo in May 1889 and stayed in the family until the National Gallery bought it in 1924.

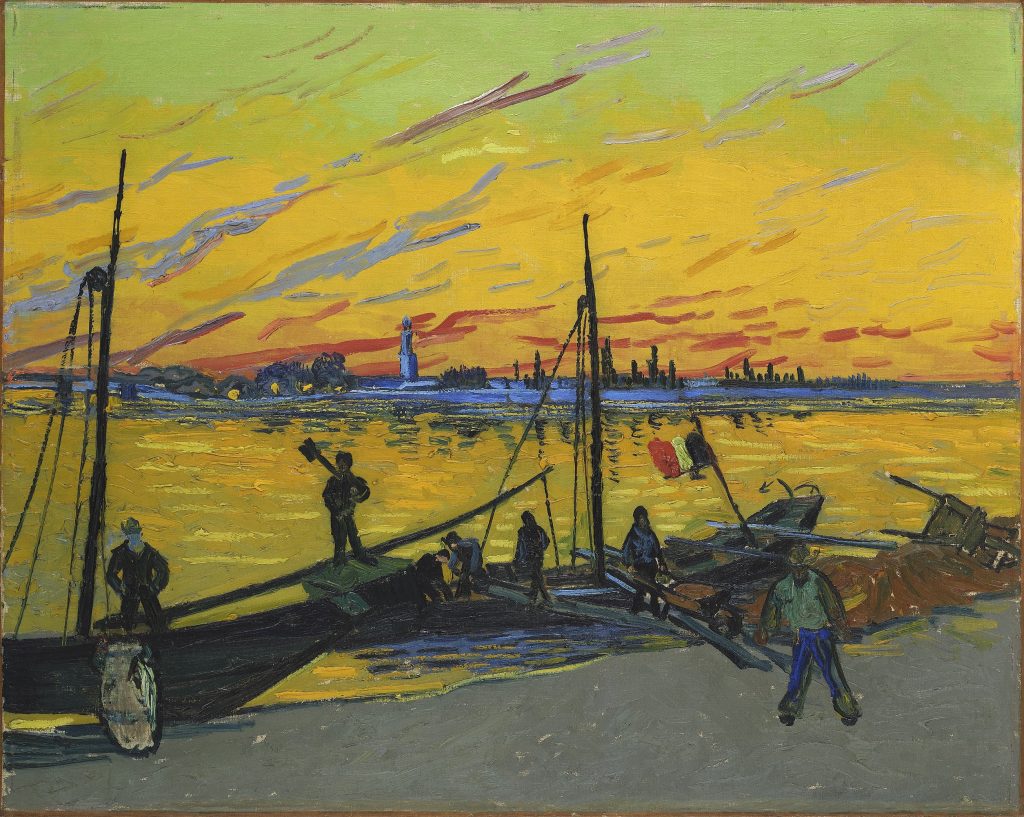

Vincent rarely missed an opportunity to set the sky ablaze. Of The Stevedores he wrote from Arles to Theo: “I saw a magnificent and strange effect this evening. A very big boat loaded with coal on the Rhône, moored to the quay. Seen from above it was all shining and wet with a shower; the water was yellowish-white and clouded pearl grey; the sky, lilac, with an orange streak in the west; the town, violet. On the boat some poor workmen in dirty blue and white came and went carrying the cargo on shore. It was pure Hokusai.”

Two lesser-known paintings, but full of interest, are on loan to the exhibition from the Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation. In Still life with coffeepot, Vincent pictured some of his few belongings at the Yellow House, doubtless choosing – as he had always done – the nearest subjects to hand to “carry on painting.” The composition was influenced by the arrangement of objects he had seen at Émile Bernard’s studio. The other Goulandris picture arose from a visit by Vincent with Gaugin to a nearby Roman-era necropolis which had become an archaeological site known as Les Alyscamps, which in the Provençal dialect means Champs Elysées or Elysium. The site is shown with only one row of poplar trees and some sarcophagi. There, Vincent conjured up a pair of lovers taking a promenade “among the dead.”

As one navigates through the exhibition’s eager crowds, the rousing ambience of the olive grove endures. Referring to five large such paintings that he had made a month earlier. Vincent elucidated in a letter to Bernard: “So at present am working in the olive trees, seeking the different effects of a grey sky against yellow earth, with dark green note of the foliage; another time the earth and foliage all purplish against yellow sky, then red ochre earth and pink and green sky.”

He is, as one aficionado has put it, “a genius who stands against everything as he cannot stop following his inner voice. Hunger or madness or whatever condition… to paint, to paint… to show the world in the way he is seeing it. The colours, the happiness, the enthusiasm of the great Van Gogh. One of the greatest. Yes, he was always rich with such a soul! His paintings are full of light, full of joy.”

Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers is curated by guest curator Cornelia Homburg who devised the initial concept, and Christopher Riopelle, the Neil Westreich curator of post-1800 paintings at the National Gallery. The exhibition has the backing of lead Philanthropic Supporter Kenneth C Griffin, founder and chief executive of alternative investment firm Citadel.

Images:

National Gallery heralds its Van Gogh spectacle.

Masterpieces include Starry Night over the Rhône and The Sower.

Sunflowers, 1888. Oil on canvas. The National Gallery, London.

The Poet (Portrait of Eugène Boch), 1888. Oil on canvas. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Bequest of Eugène Boch, 1941. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay)/ Adrien Didierjean.

The Lover (Portrait of Lieutenant Milliet), 1888. Oil on canvas. © Collection Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, The Netherlands. Photographer: Rik Klein Gotink.

Olive Trees, 1889. Oil on canvas. The Minneapolis Institute of Art, the William Hood Dunwoody Fund.

The Sower,1888. Oil on canvas. Sammlung Emil Bührle, on long-term loan at Kunsthaus Zürich. Photo © Kunsthaus Zürich.

The Yellow House (The Street), 1888. Oil on canvas. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation) © Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent Van Gogh Foundation).

Entrance to the Public Gardens in Arles, 1888. Oil on canvas. The Phillips Collection, Washington DC Acquired 1930. © The Phillips Collection.

Detail of The Public Garden, Arles, 1888. Oil on canvas. Private collection.

Detail of Path in the Park, Arles, 1888. Oil on canvas. Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo.

The Stevedores, 1888. Oil on canvas. © Private collection. Photo: Bonnie H Morrison.

Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers is at The National Gallery Rooms 1‒8, to January 19, 2025. Most ticketed times are sold out, but there are extended hours on some days, and National Gallery Members enjoy automatic free entry.