Lygia Clark and Sonia Boyce – art beyond the frame at Whitechapel Gallery

By James Brewer

A pioneering Brazilian artist, Lygia Clark, is being accorded a first major survey in a UK public gallery, 36 years after her death. Collaborative by nature, she would doubtless have been pleased that her work is being realised “in dialogue” with that of a great admirer, London-born Dame Sonia Boyce.

On the ground floor of London’s Whitechapel Gallery is Lygia’s visual – and tactile – exhibition, including at specified times live performances of a piece called Collective Body, while on the first floor is Dame Sonia’s actualisation An Awkward Relation. The two presentations with overlapping themes of interaction, participation and improvisation across the eras offer contrast but a degree of shared coherence.

Lygia was born in 1920 in Belo Horizonte, one of Brazil’s first structurally planned cities which was inspired by urban elements of Paris and New York. The Brazilian metropolis dates from the late 19th century and is associated with the great architect Oscar Niemeyer. Architectural concepts fascinated Lygia and were a prime factor in her becoming one of the preeminent artists of the twentieth century, alongside her reframing of the relationship between audience and art object. Throughout her career, Lygia’s work perpetuated that strong connection to architecture. She died in Rio de Janeiro in 1988.

Whitechapel captures the main part of Lygia’s fascinating artistic journey from the mid-1950s to the early 1970s, which was one of many politically volatile periods in Brazil when artists were trying out radical modes of practice. Hers is far from a linear narrative. She was a founding member of the so-called Neo-concrete movement, treating pictorial surfaces as if they were three-dimensional architectural spaces. Experimenting with form, colour, and plane, her early abstracts extended the visual field of painting into the physical realm of the viewer.

She and others in the avant-garde became frustrated by the limitations of geometric abstraction and wanted audiences to ‘participate’ in artworks. She was stirred by the visualisations of two great artists: the architectural and sculptural concepts of Piet Mondrian and the simple forms advanced by the Bauhaus’s Joseph Albers; and began to reduce the elements in her compositions.

She had trained in painting with the Brazilian landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx (1909–1994) and in Paris between 1950 and 1952 alongside one-time Cubist Fernand Léger (1881–1955) who had created maquettes for the designs of the great architect Le Corbusier, and with Hungarian abstract painter Árpád Szenes (1897–1985).

Some of the maquettes she produced were influenced by Russian modernist El Lissitzky and by Dutch artist Theo van Doesburg’s interior designs. She composed matchbox structures, like models for innovative buildings.

During long trips to Europe, she joined in the dynamic London art scene of the 1960s, represented her country at the 1968 Venice Biennale and launched her Corpo Coletivo (Collective Body) performance with students at the Sorbonne. In a live staging of Collective Body at the Whitechapel, seven performers dress in jumpsuits – red, green, red, yellow, pink, mauve and black – which are lightly attached together by slender threads, forcing the actors to move as if they were just one body. In balletic mode, they silently and gently writhe and intertwine.

She decided to live in exile in Paris from 1968 to 1977 in response to the most repressive phase of the Brazilian military dictatorship, which was in power from 1964 to 1985.

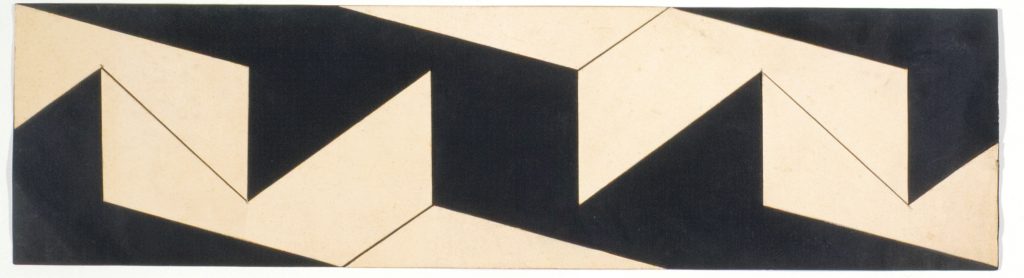

In her Modulated Surfaces series between 1954 and 1958, the line between traditional painting and architecture was dissolving, or as Lygia put it, was breaking the frame. She is quoted as saying: “What I seek is to compose a space and not compose in it.” She believed in the fusion of art and life and was inspired in her creations by the bold physical vision that shaped Bazil’s new capital Brasilia in 1960.

She beckoned people to examine her art close-up, to touch it (touching of some of the works on show at Whitechapel is encouraged) and to take part in scenarios and activities. This was ahead in time of such luminaries as body art performer Marina Abramović and even Yoko Ono, who was to introduce ‘pieces’ based on simple instructions such as “light a match and watch until it goes out.” Lygia’s approach was more understated: she rejected what she saw as the voyeuristic aspect of much performance art.

A selection in the gallery of Lygia’s Bichos (creatures), and other participatory works represent her growing interest in the therapeutic potential of art. Bichos are not animals, or anything like them. They are small hinged, flat metal sculptures that allow for the observer to manipulate and reshape them. By handing control to others to steer her sculptures through random configurations, the autonomy of the art object is changed, and the art becomes a performed event. Replica models of Bichos and other participatory works are a feature of the exhibition.

A typical instruction for Diálogo de mãos (Hand Dialogue) from 1966 encourages visitors to “wrap the elasticated Möbius strip (a mathematical structure considered a symbol of infinity) around your hands, exploring its stretchiness and tension.” Even when split down the middle the loop, with one of the ends given a half twist, turns out to have only one side and stays in one piece. The cutting operation is turned into an act of creation – the sort of transmutation of which Yoko Ono approves. It is a challenge – and great fun, incidentally.

On display are two curious blue, rubber outfits that look like what people in the 1950s used to think of as spacesuits. Participants are invited to dress in the suits which are connected by a cord, so that each occupant can explore parts of their suit and that of their partner. This is the original O eu e o tu (The I and the You) motif from 1967 which is the title for the current exhibition.

One can play with what plausibly pass for therapeutic sensory toys, such as transparent plastic bags of ping pong balls, several such items being laid out on a table.

Lygia’s work began to receive wider international attention only after her death, with a retrospective in European art institutions in the mid-1990s. Other retrospectives followed including Lygia Clark: The Abandonment of Art at MoMA in New York in 2014 and Lygia Clark: Projeto para um Planeta, Pinacoteca do Estado, São Paulo, 2023.

Sonia Boyce was introduced to Lygia Clark’s work in the 1990s and felt a strong synergy with her ethos of experimentation, observation and call to participation. The differences with Lygia’s work stem from the artistic, geographical and socio-political contexts in which the two women found themselves. Dame Sonia’s theses are predicated on the feelings of uneasiness in encounters, specifically between artists, their works and audiences. Her offering An Awkward Relation invites visitors to engage, touch and experience such works and their surroundings.

Dame Sonia is fascinated with hair as a material and as a cultural signifier. Against a background decorated with geometric structures and kaleidoscopic wallpapers, she has mounted some 20 pieces of real and synthetic hair which visitors are invited to touch. Originally included in the Do you want to touch? exhibition at 181 Gallery, London, in 1993, the hair pieces are said to address and confront deep-seated desires and assumptions. This was further explored in 50 collages from Black Female Hairstyles (1995) and a 2005 video Exquisite Tension.

Finally, Dame Sonia has a large, seven-channel audiovisual called We move in her way based on a performance at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts in 2017. That 18-minute production references in part the Swiss designer and Dadaist Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889-1943) who in the 1920s and 1930s combined traditional crafts with modernist abstraction. The performance unfolds with men and women in silver leotards toying with fabrics and reacting with each other and their surroundings.

Whitechapel Gallery is a prominent supporter of Sonia Boyce, a British Afro-Caribbean who came to prominence in the early 1980s in the British Black Arts Movement with figurative pastel drawings and photo collages that addressed questions of race and gender. In 2022, she presented Feeling her Way for the British Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale for which she was awarded the Golden Lion for best national participation. She became a professor at University of the Arts London, where she holds the inaugural Chair in Black Art & Design, in 2014.

Images:

Corpo Coletivo (collective body) by Lygia Clark performed at Whitechapel Gallery, October 2024.

Bicho, 1960-84. By Lygia Clark. Steel Installation. Courtesy Alison Jacques, London © O Mundo de Lygia Clark-Associação Cultural, Rio de Janeiro. Photo: Michael Brzezinski.

Planos em superfície modulada, 1957. By Lygia Clark. Collage, cardboard. Photo Marcelo Ribeiro Alvares Corrêa. Courtesy of Associacão Cultural O Mundo de Lygia Clark.

We move in her way, 2016. By Sonia Boyce. Production still from seven synchronised videos with sound and wallpaper installation. Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 2017. Photo: George Torode © Sonia Boyce. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2024. Courtesy of the artist, APALAZZOGALLERY and Hauser & Wirth Gallery.

Portrait of Sonia Boyce. Image: Parisa Taghizadeh. © Sonia Boyce. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Armitage 2024 Courtesy of the artist, APALAZZOGALLERY and Hauser & Wirth Gallery.

Sonia Boyce: An Awkward Relation, in dialogue with Lygia Clark: The I and the You is at the Whitechapel Gallery, 77 – 82 Whitechapel High Street, London E1, until January 12, 2025.