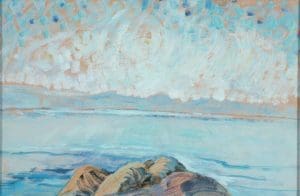

Untitled (Seascape), 1935, By Emily Carr, Oil on paper mounted on board. The Art Gallery of Greater Victoria.

Canada’s most remarkable woman will be celebrated in Dulwich Picture Gallery’s 2014 programme – as will David Hockney, and a circle of 1920s British artists, By James Brewer

For much of her life, Emily Carr, born in Vancouver Island, believed she had been rejected by the art world. Sixty-eight years after her death, one of the globe’s top cultural institutions – Dulwich Picture Gallery – is preparing the first major exhibition in the UK dedicated to her pioneering modernist works.

Happiness, 1939. By Emily Carr. Oil on paper, University of Victoria Art Collection, Gift of Nikolai and Myfanwy Pavelic.

Her lush depiction of what was in some eyes just wilderness will triumphantly round off the gallery’s ambitious 2014 programme, which will start by lauding the printwork of one of the greatest living artists, David Hockney, and go on to celebrate the circle around 1920s artists Ben and Winifred Nicholson.

Emily Carr took ship along the Pacific coast of Canada to plunge into the backwoods of British Columbia again and again to paint bold forest scenes, indigenous themes and dramatic skyscapes and landscapes.

What she perceived as her lack of success led her to abandon painting for 15 years, but the achievements over her lifetime, 1871 to 1945, led her to be described as “quite possibly the most remarkable woman in Canadian history” in the book Great Canadians: a Century of Achievement, edited nearly 50 years ago by the pre-eminent historian Pierre Berton.

One wonders what she would have thought of London hosting such a great show of her works – she topped off her training at Westminster School of Art, but she hated the polluted state of the capital and spent time in a sanatorium suffering from what may have been a nervous breakdown. The first turning point in her career was in 1907 when she voyaged up the Canadian coast as far as the Arctic and set out to record the continent she had ‘discovered.’

Indian War Canoe (Alert Bay), 1912. By Emily Carr. Oil on cardboard. Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, purchase, gift of A Sidney Dawes.

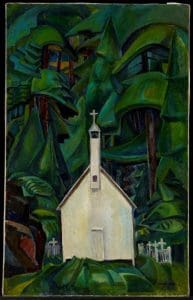

The exhibition will make clear that she was an early advocate for the dignity and importance of aboriginal peoples and their culture, by including art and artefacts from the First Nations.

Redoubtable Emily travelled alone in increasingly difficult conditions, said Ian Dejardin, Sackler director of the Dulwich gallery (the directorship position is endowed with a generous grant in perpetuity from the Dr Mortimer and Theresa Sackler Foundation) and who is curating the show jointly with Canadian art commentator Sarah Milroy. Far from any studio, Emily would pin a sheet of paper on any piece of wood she could find, such as a barn door, and paint on the spot. She took a battered old caravan she called The Elephant into the forest with a menagerie of pet animals she loved. By 1910 she was the most sophisticated and forward looking painter in Canada, but soon afterwards cast her equipment aside, until a fateful meeting with Lawren Harris, the dynamo of the Group of Seven painters who were committed to exploring the rugged landscapes of their country, and being “completely in awe” of his work, said Mr Dejardin. She was galvanised to return to action at the age of nearly 60 as Harris reassured her: “You are one of us.”

The Schooner the Beata, Penzance, Mount’s Bay, and Newlyn Harbour., By Alfred Wallis., Oil on board. Private Collection/Copyright Winifred Nicholson

Four Luggers and a Lighthouse, c 1928., Oil on card. By Alfred Wallis. Private Collection, on loan to Middlbrough Institute of Modern Art

She said that 10m cameras could never show the real Canada. It had to be passed through live minds, sensed and loved.

The Group of Seven, all men, encouraged many women artists, and there was a great flowering of female artists from that time. A rightful measure of fame came to Emily late, with the publication of an award-winning book in 1941. Mr Dejardin said of her until that point: “Although she thought she was rejected and unappreciated , she was probably pretty well known as an artist. When she goes to Ottawa and Toronto, she does attract national attention.”

One work Mr Dejardin described as “an extraordinary vortex of trees, ” while another showing a war canoe had “glorious colour and brush-strokes.” In all, said Mr Dejardin, the legendary artist was “a woman of extraordinary determination and rigour. Emily Carr was always the rebel, but she knew she wanted to be an artist.”

The exhibition, full title Painting Canada 2: Emily Carr and the Indigenous Art of Canada’s Northwest Coast, will run from November 1 2014 to February 22 2015. Mr Dejardin said that many visitors to the gallery’s earlier show Painting Canada: Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven, one of its most popular – had beseeched him “When are you going to do Emily Carr?” so “I took the hint.”

There will be more than 100 of her works mostly shipped from Canadian galleries to the stately south London building which began life in 1811 as England’s first purpose-built public art gallery. Designed by Regency architect Sir John Soane, it boasts a permanent collection of many wonderful old masters.

(Cornish port), c 1930. By Ben Nicholson, Oil on card. Copyright Kettle’s Yard/Angela Verren-Taunt 2013. All rights reserved, DACS.

Dulwich starts its new programme with an exhibition from February 5 to May 11 of printwork by David Hockney. This will mark 60 years of Hockney’s printmaking, and curator Richard Lloyd of Christies observes that Hockney “is still searching, still experimenting” in the discipline. The show will help remedy the wrong that Hockney’s talent in etching and lithography has been overshadowed by his painting. Among intriguing examples will be one of his first works in which, says Mr Lloyd, “I think he tried to make himself look like Stanley Spencer.” Mr Lloyd said that “lithography is a tricky medium to work in, but a fabulous way of making images.”

Indian Church, 1929. By Emily Carr. Oil on canvas. Art Gallery of Ontario, bequest of Charles S Band, Toronto, 1970.

Dulwich’s summer exhibition, from June 4 to September 21 2014, will be entitled: Art and Life: Ben Nicholson, Winifred Nicholson, Christopher Wood, Alfred Wallis, William Staite Murray, 1920-31. Touchingly, it will be curated by the Nicholsons’ grandson, art historian Jovan Nicholson. Landscapes, seascapes, still lifes and portraits often of a naïve nature will be on show. The couple’s output was prolific, particularly during their 10 years of marriage, and they had exceptional friends including Alfred Wallis who made paintings from old crates and ship paint.

Herring Fisher’s Goodbye. Oil on board, 1928. By Christopher Wood. Private Collection. Copyright Winifred Nicholson Trustees

Winifred had a wonderful way with words. Talking of one of Wood’s paintings, she said: “The sea is not so much salt water but the ebb and flow and depth of anguish.” She said that boats “are courage itself.”

Self Portrait, 1954. By David Hockney. Lithograph in five colours. Copyright David Hockney

Launching Dulwich’s 2014 programme at Canada House, Trafalgar Square, the High Commissioner to the UK Gordon Campbell said that the premises was intended to be more than a centre of diplomatic activity and immigration processing; it served as a centre for culture and discussion of public issues. Mr Campbell, who earlier in his career served three terms as premier of British Columbia, said that his first major diplomatic appointment after being appointed High Commissioner in September 2011 was to open the Tom Thompson and the Group of Seven exhibition at Dulwich. He described Emily Carr as “one of the truly great Canadian artists. It will be a show like no-one has seen in Canada, and will touch the hearts of people throughout the UK.”