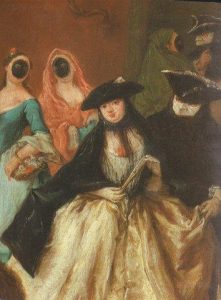

Al Ridotto. Oil on canvas. By Pietro Longhi

Uncovering the hidden visages of Venice: Marie Ghisi’s new book ‘The Venetian Mask: the Bauta as a Political Asset’, Review by James Brewer

Amid the splendour and pomp of Venice at the height of its glory, political power lurked beneath… a stark white mask. The sinister-shaped facial covering was, for centuries, a political and social accessory to the governance and expansion of the city state.

Marie Ghisi seeks to explain in The Venetian Mask: the ‘Bauta’ as a Political Asset why this was so, and how the mask became the erotic and elusive face of the Most Serene Republic of Venice.

She is highly qualified to do so, as a historian, and as a descendant of one of the great families that settled in Venice during the 12th and 13th centuries. During the fourth crusade, which got side-tracked from its mission to reach Jerusalem and became an empire-building spree in which Constantinople was sacked in 1204, the ancestral Ghisi family helped conquer some of the Aegean islands. The Ghisi governed the islands for many years, until later Turkish successes prised them away in a wider loss of territory that was a severe blow to Venetian morale.

Mrs Ghisi’s book, from the Italian publishing house La Toletta, named after a famed Venetian bookshop, seeks to unlock the mysteries of why the Venetians were so – shall we say attached – to their masks, and the luxurious fashions that at some stages completed the attire. She does so in a series of short, elegant, pearl-drop chapters.

Dama con mascherina. Oil on canvas. By Felice Boscarati

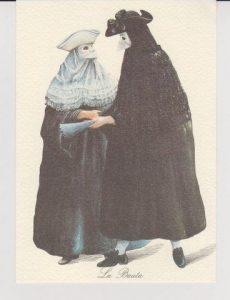

Designed so that the wearer could talk, eat and drink without removing it, the bauta would typically be worn with a white or black cape and, in the 18th century, a wide black hat, the tricorno.

Why was the bauta for gentlemen and the version for ladies, the moretta, worn year round, and not just at Carnival? Casanova gives us a clue when he describes the moretta as “the naughtiest mask imaginable.” He was talking not just about the mask – the faces of the ladies might have been hidden, says Mrs Ghisi, but “their cleavage, their painted red nipples, ” were enhanced by the silence enforced by the need to hold the ribbonless masks in place by biting on a small bead fastened to the inside of the mask. In their turn, women considered the bauta to be sexy and made men irrestistable even when they were otherwise hopeless at courting.

The familiar white mask is seen in the paintings of Pietro Longhi, Francesco Guardi, Canaletto and others, but there are many myths shrouding the subject. This is why Marie Ghisi undertook to bare the mystery by delving deep into Venetian history. The reader will discover the subtlety of etiquette as practised in the mighty Serenissima Repubblica, the contradictions at the heart of the exaggerated rules of conduct, and the the role of the bauta in the tumultuous ebb and flow of internal politics.

The edicts of the Maggior Consiglio – the Great Council, the highest political organ of the Venetian republic – reveal that there were times when it was forbidden under strict penalty to wear the bauta; at other times its proper use was defined and enforced by law. One rent in Venetian garments could never be fully obscured – the gap between the wealthy and the majority of citizens, although the Maggior Consiglio was more concerned at stamping out aristrocratic plots, real and imagined, to overthrow its rule.

Nobili in maschera. Water colour. By G Grevembroch.

Mrs Ghisi insists on the political role of the bauta, in keeping the peace between rich and poor: “Under the bauta everybody is equal, ” it was said. Thus was Venice able to avoid riots and revolt for many centuries.

Noblemen took to their cover-up with gusto, emboldened to do as they pleased under the cloak of anonymity, striding in their swaying black outfits to secret meetings and assignations unchallenged.

Built on 118 small islands, Venice had under its ruling Doges grown from a few impoverished huts in a muddy lagoon into a maritime superpower, to the extent that it possessed the biggest shipyard in the world, one that built an entire galley in a day to impress the visiting King Henry III of France – at a time when Plymouth, a busy dockyard in England, would take a whole month to build such a ship.

Such accomplishments could be frittered away: some of the nobles who made their fortune from trade and shipping gambled it away in an evening in the city’s semi-clandestine casinos. They could be seen early in the morning leaving the gaming hall of the Ridotto, in one of the city’s mansions, the palazzi, nearly naked, having literally lost the clothes on their back. Masks were useful here in the function of shielding the shame of falling into ruin. In 1703 the Maggior Consiglio prohibited the wearing of masks in the Ridotto, and later shut the place, which had the effect of forcing gambling, at an even more feverish pace, back into private homes.

La Bauta. Water colour. By Uwe Thurnau.

Marie Ghisi

Weakened by military defeats and the Portuguese entry into the spice trade, Venice was unable to repel the victorious army of Napoleon, who in 1797 forced an end to the traditional form of city government. The maritime power Venice had wielded since the 10th century was at an end.

It is poignant for Mrs Ghisi to recall that a member of her family served on the Maggior Consiglio from 1179 until the end of the republic. She has other ancestral connections to the ruling elite: two daughters of the Ghisi line married important Doges, each becoming Dogaressa of Venice. In 1268 Agnese Ghisi married Lorenzo Tiepolo, and Marchesina Ghisi married Lorenzo Celsi in 1361. The Doges were as powerful as kings, and they would every year ceremonially cast a gold ring into the Adriatic in recognition that the fate of the state was wedded to the sea.

With the victory of the French, Venice had to divorce itself from its rule over the eastern Mediterranean. Under revolutionary decrees, wearing the bauta, even at Carnival, was declared illegal, and Napoleon’s troops began an orgy of iconoclasm. A modest revival of the mask customs had to wait until the city came under prtection of the Austrians.

Povero in maschera. Water colour. By G Grevembroch

Marie Ghisi, who in her time has been a jewellery designer under the name of Marie Storms to royalty, and who enjoys leading exclusive tours showing visitors the secrets of the palazzi, walks the reader of her book in a delightful passeggiata unmasking a wealth of detail and Machiavellian power plays concealed behind a seemingly simple Venetian indulgence.

The Venetian Mask: The ‘Bauta’ as a Political Asset, by Marie Ghisi. Published by La Toletta edizioni, Venice. www.tolettaedizioni.it The book is also available at Daunt Books, Marylebone High Street, London.

1 comment

A fascinating story full of real and lived Venetian history. Countess Marie Ghisi will come and talk about it in one of her lectures at the Accademia Italiana in 55 exhibition Road London SW7 in the next months.

An excellent review by James Brewer. Thank you Rosa Maria.