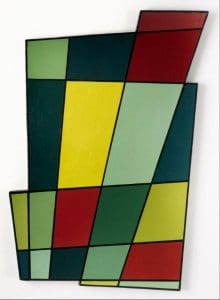

Irregular Frame No. 2, 1946. Oil on plywood. By Juan Mele. Coleccion Patricia Phelps de Cisneros.c Estate of Juan Mele.

Radical Geometry: the modern art of South America at the Royal Academy, By James Brewer

A rare glimpse of how 20th century social and political upheavals in South America generated vibrant modern art movements is being offered in London by the Royal Academy of Arts.

International trade surges and slumps exerted considerable influence on the practice of young artists, and what happened from the 1930s to 1970s is charted in the show, Radical Geometry: Modern Art of South America.

Exhibition curators Dr Adrian Locke of the Academy, and Gabriel Pérez -Barreiro of the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, bring to refreshing prominence a period of experimentation that has been neglected by Eurocentric and US-centric historians, and that should not be divorced from the ‘mainstream.’

The featured artists had a difficult time interacting with the authorities. None of them were successful commercially, and they had to row back on their innovation when military regimes, particularly in Brazil, imposed censorship. They stuck to their principles though, and continued to raise questions about the nature of art and its place in the world.

Essentially they took up the dropped torch of geometric abstraction, which was lit soon after the Russian Revolution. Behind what appear to be fairly straightforward lines on the canvas lies a turbulent back story of intellectual flowering germinated in the great metropolises of Montevideo, Buenos Aires, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Caracas.

The profusion of ideas can be traced to the arrival In 1934 of a ship in the Uruguayan capital carrying home 60-year-old artist Joaquín Torres-García after years spent in Barcelona, Paris and New York. He brought with him an unlikely confluence of inspirations: meeting the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian who experimented with the boundaries of form, and viewing in a Paris museum the geometrical aspect of ceramics from the Inca age.

Sphere, 1976. Stainless steel. By Gego (Gertrude Goldschmidt). Coleccion Patricia Phelps de Cisneros. c Fundacion Gego.

Torres-García declared a new concept of art, drawing on such pre-Columbian influences as the Incas. To connect the ancient and the modern, he worked in geometric rows, some filled with symbols and letters so that the art looked backwards in time and forwards. He wrote extensively on his theories under the banner of Constructive Universalism, although winning few followers.

Across the River Plate, a decade later, a group of artists distanced themselves from Torres-Garcia whom they dismissed as old-fashioned. Some of them were second generation immigrants and unlike the Uruguayan master, had never been overseas.

They still turned their sights across the Atlantic, and tore up the rules of traditional painting, most signally abandoning the conventional shape of the frame. Strongly left-wing in reaction against the fascism that had confronted the liberal democracies and the Soviet Union, they hauled out of disuse the style of Russian Constructivism, and even refused to sign their work which they considered a bourgeois practice.

Argentina had prospered by its ostensible neutrality in the war that fuelled its grain and livestock exports, and had welcomed a cream of intellectual refugees from Europe. Uneasy over the global scene, artists banded together to issue revolutionary manifestos – the Royal Academy show could have added a useful service by including extracts from such declarations.

Fertile ground for free-wheeling political positions dwindled as the autocratic Juan Domingo Perón came to power, and as the economy was rocked by the collapse of markets for the country’s produce. There was an exodus of radical artists for Europe.

The exhibition ‘moves north’ to Brazil to look at new approaches to painting and sculpture in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro in the 1950s and 1960s. Long before the BRIC era, Brazil was aspiring to be a super-power with its own manufacturing base. Concretely this showed up in ambitious projects in architecture, with the construction of the new capital Brasilía from scratch: a city that is a beacon of radical geometry in its buildings and urban lay-out. The new São Paulo Biennial and exciting galleries attracted international contemporary art.

Chromatic Rhythms II, 1947. Oil on canvas. By Alfredo Hlito. Coleccion Patricia Phelps de Cisneros. c Sonia Henriquez Urena de Hlito.

While São Paulo artists plumped for a machine aesthetic, which was ‘capable of practical applications, ’ in Rio the geometry was perhaps a reflection of the relaxed lifestyle and exuberant nature of the beachside city, the curators going so far as to say that the works were ‘a little more bossa nova.’ For instance, the practitioner Hélio Oiticica created a wearable geometric composition that was used in the city’s Samba School. Repression was to cast a dark shadow cross the arts scene when a military coup initiated a reign of terror in 1964.

The exhibition ends in Caracas, where the Venezuelans took a more scientific approach to sequence and series. Caracas held its head high with urban projects such as University City, designed by Carlos Raúl Villanueva and inaugurated in 1954, which made use of brilliant light effects and incorporated works by American, European and local artists. The new generation took this as an invitation to join the fray. This they did with gusto. Carlos Cruz-Diez and Jesús Soto produced compositions that change colour. Carlos Cruz-Diez is still going strong, and was commissioned to design the 2014 repainting in ‘dazzle camouflage’ of the historic pilot ship Edmund Gardnerconserved by Merseyside Maritime Museum in a dry dock next to Albert Dock in Liverpool. Dazzle painting was seen as protecting British naval and trade vessels during the First World War.

A great highlight of the Royal Academy show is a series of sculptures hand-crafted by Hamburg-born Gego (Gertrude Goldschmidt), such as Trunk, from 1976, and Sphere, from 1976. The finely wrought, three-dimensional structures induce a sense of wonder: they are a kind of drawing without paper, in steel, copper, stone, lead, iron, aluminium, plastic and wire. Some of the results are in the style of delicate mobiles.

Construction in White and Black, 1938. Oil on paper mounted on wood. By Joaquin Torres-Garcia. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Patricia Phelps de Cisneros in honour of David Rockefeller, 2004. Photo Coleccion Patricia Phelps de Cisneros.

In all, Radical Geometry has more than 80 paintings and sculptures, mainly from the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, which is said to be the foremost collection in private hands of geometric abstract art from Latin America. Additional loans are donations by Ms Phelps de Cisneros from the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Founded in the 1970s by Ms Phelps de Cisneros and her husband, media tycoon Gustavo A Cisneros, the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros is based in New York and Caracas.

Radical Geometry: Modern Art of South America from the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Collection is at the Royal Academy until September 28 2014.