Exhibition banner

Revolution: Russian Art 1917 – 1932 unfurled at Royal Academy

By James Brewer

Every artist at work at the time of the October 1917 Revolution poured out an immediate emotional response to the historic overthrow of Russia’s ruling class. This ranged from rejoicing to revulsion, with some initial supporters sapped by disillusion or a sense of betrayal of the liberal norms for which they had hoped.

Cast of Vera Mukhina’s Flame of the Revolution and banner All power to the Soviets. (1)

As the Royal Academy of Arts makes blazingly clear in its magnificent new exhibition, there were in the early years of the new order great leaps forward in all fields of creativity and design. Signature works burst forth, building on the ingenuity of members of the avant-garde who were already in full flow in the first decade and a half of the 19th century.

Revolution: Russian Art 1917 – 1932 achieves its goal in being a vivid evocation of the turbulent epoch it scrutinises, embracing the triumphs of art, its hagiographic embarrassments and the suffering of innocent peasants, intellectuals, skilled professionals and the artists themselves.

Dish with inscription Sailor’s Walk, 1 May 1921. By Alexandra

Shchekotikhina-Pototskaya. (2)

It delves into the quotidian impact of the transformative period, bringing it to life for instance with a full-scale recreation of a ‘modern’ functional apartment designed by one of the top artists, El Lissitzky (1890-1941) for communal living, and with objects and ephemera from textiles to brilliantly original porcelain, to 1920s ration coupons. Designs modelled on the Suprematist school of abstract art printed on vouchers for bread and other foodstuffs would have been familiar to the millions of Russian citizens through whose hands they passed, albeit the symbol of grave grain shortages in a land capable of plenty.

Such incidentals as the imprints on the coupons are the minor but meaningful details of the bigger picture of sweeping changes that shook the nation to its core and thrust Russia to the centre of world attention and hopes for social change elsewhere.

The London exhibition focuses on the attempts to consolidate the October Revolution, until the slamming of the door on the avant-garde and all innovation in 1932 when Stalin and his acolytes began a violent repression on perceived threats to his dominance. Hitler was about to do the same thing in Germany, another cradle of early 20th century creativity.

From the opening section, Salute the Leader, reflecting Lenin’s seizure of power and cult status, the visitor is plunged into a vortex of societal upheaval illustrated by more than 200 exhibits including choice loans from the State Russian Museum in St Petersburg and the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

Malevich room.

Soon after 1917, the contribution that art could make was seized upon by its practitioners and by the new state leaders as a kind of ‘new technology,’ a perfect means of mass communication in a country where most of the huge population was illiterate. There were only 250,000 Bolsheviks and they needed to get their message to the masses. New and newish interpretations were poured into every form of expression, especially cinema, posters, banners and sculptures, and into household objects.

When the Imperial Porcelain Factory at Petrograd (known as St Petersburg until the outbreak of World War I, and changed back to that in 1991) was taken over by the state, some of the ceramicists of the city soon to be known as Leningrad for the next 66 years moulded the materials available in honour of Communism. Some items pictured everyday scenes, and others had painted on them references to conceptual trends.

At the Royal Academy, we see for instance a dish with the inscription Sailor’s Walk, 1 May 1921. Considerable skill has gone into this design by Alexandra Shchekotikhina-Pototskaya, who applied enamel paint on porcelain, silvering, gilding and etching. She had worked for Sergei Diaghilev, and had experience in graphics and theatre design. Her works have been described as a riot of imagination.

Displayed in a nearby case is a coffee pot and plate with Suprematist design, by Nikolai Suetin (1897-1954). Suetin and Kazimir Malevich, primarily known as painters, seem to have happily shared their talents with the ceramics branch.

Malevich (1879-1935) was the father of Suprematism, which is based on forms such as circles, squares, triangles and rectangles, painted in modest colours. Malevich coined the name of such art which he insisted would be superior to the art of the past, leading to the “supremacy of pure feeling or perception in the pictorial arts.”

VI Lenin and Manifestation, 1919. By Isaak Brodsky. (3)

He believed that the Cubists had not taken abstraction far enough. He contended that the perception of such forms should be free of logic and reason, for the absolute truth can only be realized through pure feeling. He was globally influential on modern art, and his Black Square (first version from around 1915) is the best-known piece.

Black Square is ‘just’ a square of black paint on a white background although one can make out brushstrokes, fingerprints, and colours beneath the black layer. His Red Square of the same year as Black Square has a second title, Visual Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions, the visual element having been distilled into “pure feeling.”

His disciple Lissitzky believed that art and life were complementary. He identified the graphic arts, particularly posters and books, and architecture as ideal ways of reaching the public. He wrote: “Suprematism has advanced the ultimate tip of the visual pyramid of perspective into infinity.” One of the most memorable of Lissitzky’s studies is Beat the Whites with a Red Wedge piercing a white circle, which is often interpreted as a paean to the Red Army, but the red could also be a symbol of blood.

For 15 years, barriers the possibilities of experimenting with a proletarian-orientated art seemed limitless, but there began to be worrying signs. Arrests by the state began as early as 1929, foreshadowing the mass purges that were to course through society in the 1930s.

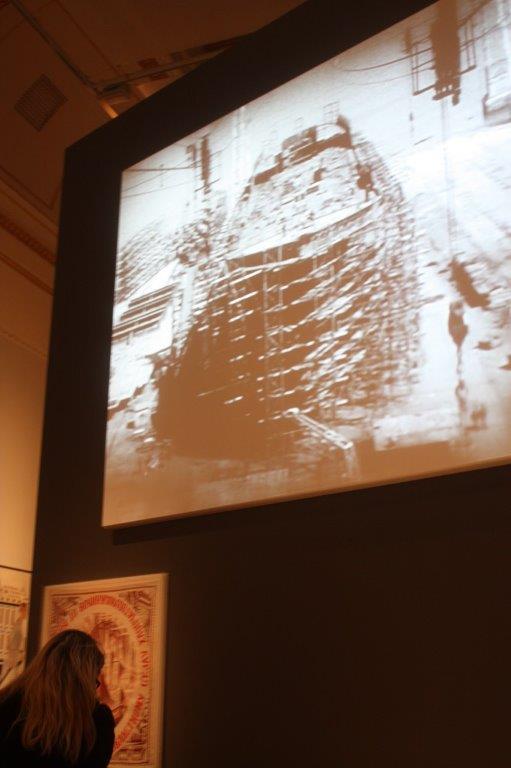

Shipyard No 1. From film The Deserter. (4)

The arts had initially thrived even through the civil war against the western-backed Whites, and amid the period of War Communism (1918-21) which brought malnutrition and horrendous overwork. Debates swirled over what form a new “people’s” art should take and art flourished across every medium. Alarmed, Lenin brought in the New Economic Policy which revived some free market functions, and food production increased, but it shrank again following collectivisation of agriculture in 1928 when the ration cards had to be brought back.

The London spectacular takes its template from a huge exhibition in Leningrad just before Stalin’s brutal clampdown. The Soviet showcase sought to summarise through 2,640 paintings from 423 artists across 35 galleries the best of the diversity and richness of art in the preceding 15 years, but it had a bitter-sweet reality. It was “the last call for freedom of the arts,” say the curators of the 2017 show.

In April 1932, it was decreed that art must depict the struggle for socialism. The creative artist must serve the proletariat by being realistic, optimistic and heroic. From then on, the orthodoxy of so-called Socialist Realism, which would come to define Communist art as that which was acceptable to the regime, was “the only way.”

Malevich was given his own room in the 1932 exhibition. That can be construed either as a tribute to the man, or an attempt to wall him off from his contemporaries. The Royal Academy recreates the Malevich room with 30 of his paintings and architectons (architectural maquettes envisioning a reformed lived environment) seen together for the first time since 1932.

Also given a room of his own work in 1932 was Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin (1878-1939). A writer and violinist as well as a painter, Petrov-Vodkin was born in a small village by the Volga River. In 1932 he was appointed president of the new Leningrad Regional Union of Soviet Artists, a system set up to exert control over artists, and his output of acceptable works helped him to survive.

Petrov-Vodkin was one of the few artists permitted to make sketches of Lenin in his coffin, as the leader lay in state in 1924. The painting he made as a result has rarely been seen and is usually in storage at the State Tretyakov Gallery, the reluctance to display it being a legacy of the perceived immortality of Lenin’s guiding role.

Coffee pot and plate with Suprematist design. Nikolai Suetin.

When the Leningrad exhibition was transferred to Moscow in 1933, it was enlarged but many of the radical works were omitted. The curator Nikolai Punin was later to be arrested for speaking out in favour of persecuted artists and in 1949 was sent to the Gulag, where he died in 1953. Malevich, who had already been interrogated by the NKVD secret police, was far less visible in the Moscow show. Museum curators, artists and families began to hide works which might offend the ruling clique from sight.

Unlike the 1932 exhibition, the Academy includes much more than paintings. It surveys the entire artistic landscape of post-Revolutionary Russia. There is photography, sculpture, and filmmaking.

The great director Sergei Eisenstein (Battleship Potemkin and Strike, 1925) and cinéma-vérité pioneer Dziga Vertov became skilled exponents of politically charged cinema. The newsreel series, Kinodelia (Film Weekly) and Kinopravda (Film Truth) run by Vertov, used inter-titles designed by Alexander Rodchenko in a Constructivist style (in which mechanical objects are combined into abstract mobile forms). Rodchenko (1891-1956) also produced their advertising posters: it was a golden era for graphic design.

We see a clip of 1 minute 9 seconds from the 1933 film The Deserter. Directed by Vsevolod Pudovkin, the film is set principally in “a foreign shipyard that is building an order for the Soviet Union.” It follows the fate of a Hamburg worker commissioned by the USSR to organise a strike, and the pressures created by the violence of the struggle.

Textile Workers, 1927. By Alexander Deineka. (5)

It is sometimes overlooked that Kandinsky (who had returned to Russia from Germany in 1914) and Chagall, who are represented here with their distinctive compositions, initially took public roles in the Bolsheviks’ cultural institutions. Both emigrated in the early 1920s.

Women meanwhile were granted equal rights, although this was a means to draft them into the hard-driving workplaces. Film, music and painting depicted the super-heroes and heroines of industrialisation. Their idealisation is seen in such works as the female Textile Workers painted in 1927 in oil on canvas by Alexander Deineka who went on to eulogise the type of sportsmen and women pictures beloved of the Stalinist authorities.

A room at the academy is devoted to the fate of the peasants, millions of whom died through the failures of collectivisation which gave rise to state terror and starvation. Malevich blanked out the faces of peasants in an obvious gesture of sympathy for their plight. The playwright Vladimir Mayakovsky, who is referenced several times in the exhibition, bitterly criticised the way things were going and in 1930, shot himself in his Moscow apartment.

Viewing works of Wassily Kandinsky.

Vera Mukhina (1889-1953), who has been described as the queen of Soviet sculpture, is represented by a bronze cast based on her unrealised 1922 design Flame of the Revolution. Born in Riga, she was educated in Moscow and Paris and promoted imposing propagandising monuments throughout the country.

Towards end of the show we come to a ‘black square’ of a different stripe: a dark mini-cinema with a video roster of police-cell photos of the exiled, the starved, the murdered in Stalin’s purges: housewife Olga Pilipenko, a Latvian language teacher, the former chair of the hydro-meteorological committee, peasants, short-story writers, poet Osip Mandelstam, Nikolai Punin and many other established and promising artists and scientists.

There is an interesting Greek connection to some of the works on display. The State Tretyakov Gallery came to possess one of the most significant private art collections of the 20th century, which had been built up by George Dionisovich Costakis (1913-1990). A Greek national, Costakis was born in Moscow and spent most of his life working in the Canadian embassy. In the 1960s and 1970s, his home was a place where young artists could become acquainted with the works of the Russian avant-garde. Under surveillance by the security forces, Costakis decided to move abroad in 1977 but was obliged to leave much of his collection behind.

Fantasy, 1925. By Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin. (6)

The exhibition is brilliantly curated by Ann Dumas of the Royal Academy, with John Milner, professor of the history of Russian art at the Courtauld Institute of Art, and Dr Natalia Murray, curator and lecturer in Russian art at the Courtauld Institute.

Financial supporters of the deeply-moving exhibition are LetterOne, a Luxembourg-based investment business focused on the telecoms, technology and energy sectors; and the Blavatnik Family Foundation. LetterOne is led by Ukraine-born Mikhail Fridman who is chairman of the supervisory board of Alfa Croup Consortium, one of the Russia’s largest privately owned financial and industrial conglomerates. The Blavatnik foundation is headed by US-based Leonard Blavatnik, also born in Ukraine and who founded Access Industries, a private investment company with holdings in the oil, chemical, and many other industries.

Revolution: Russian Art 1917–1932, main galleries, Royal Academy of Arts, until April 17 2017.

Notes to picture captions:

(1) Vera Mukhina. Flame of the Revolution, bronze cast of 1954. State Tretyakov Gallery. Design honouring the revolutionary Yakov Sverdlov. Banner slogan All power to the Soviets. Reconstruction by India Harvey 2016.

(2) Alexandra Shchekotikhina-Pototskaya. Dish with inscription Sailor’s Walk, 1 May 1921. Enamel paint on porcelain, silvering, gilding, etching, state Porcelain Factory, Petrograd. Petr-Averi Collection.

(3) Isaak Brodsky, VI Lenin and Manifestation, 1919. Oil on canvas. State Historical Museum Photo (c) Provided with assistance from the State Museum and Exhibition Centre ROSIZO.

(4) Shipyard No 1. From film The Deserter. 1933. Vsevolod Pudovkin. Scene shows a Hamburg shipyard building an order for the Soviet Union.

(5) Alexander Deineka, Textile Workers, 1927 Oil on canvas, State Russian Museum, St Petersburg.

(6) Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, Fantasy, 1925 Oil on canvas, State Russian Museum, St Petersburg.