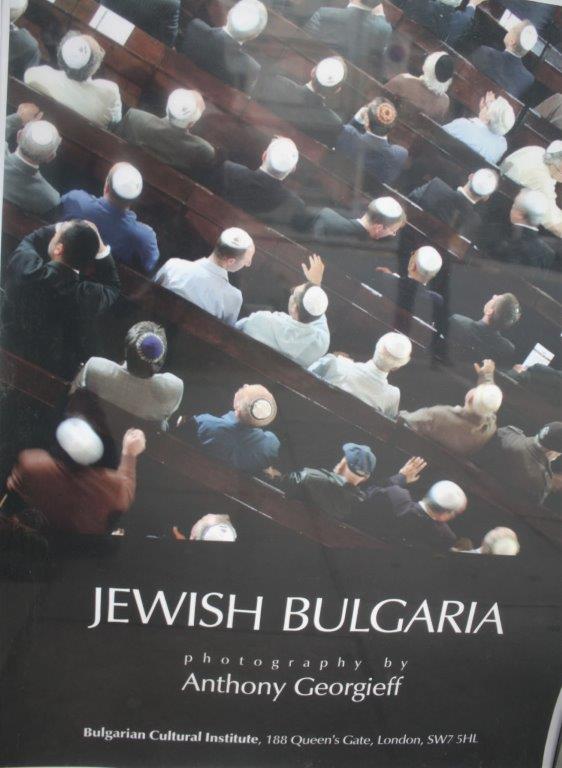

Jewish Bulgaria, photography by Anthony Georgieff

By James Brewer

A half-forgotten chapter of 20th European century history emerges from the shadows in a new exhibition in London. The episode has its shameful elements but is one that in large part brings out the better predispositions of humanity.

Jewish Bulgaria, an exhibition of photography by journalist and author Anthony Georgieff, is a remembrance of the resistance of a Balkan nation to Nazi pressure to corral its Jews for despatch to extermination camps.

Bulgaria is in 2018 remembering the 75th anniversary of a narrow reprieve for Jews in Bulgaria, but the contemporaneous deportation of more than 11,000 Jews from annexed territories to their deaths at the notorious Treblinka installation, northeast of Warsaw in occupied Poland. The deportees were taken from parts of northern Greece and Yugoslavia, whose absorption into Bulgarian administration had previously been brokered (peacefully!) by Hitler.

Speaking at the opening of the exhibition, which runs until early August 2018, Mr Georgieff said that he sought to bring to public attention a period that in effect “nobody knows about,” yet was an integral part of the history of Bulgaria, a country little known outside of eastern Europe. The chronicle of the Jews in Bulgaria had been pushed into the background as Nazi domination was succeeded by the Communist regime. “Our job as journalists is to tell the truth,” he said.

On display at the Bulgarian Cultural Institute in Kensington are 34 of Mr Georgieff’s images together with his summary of the Jewish predicament in his native country. Born in the Black Sea port city of Bourgas, Mr Georgieff moved to Denmark in 1989 and pursued a varied media career in Copenhagen, London, Munich and Prague. He is now in magazine and book publishing in Sofia.

He said that Bulgaria “famously did not deport about 48,000 Jews during the Second World War. In 1943, before it had emerged that Nazi Germany would be losing the war, the Kingdom of Bulgaria, a German satellite, failed to do what had been expected – despite all the plans, the array of barges and the waiting cattle cars.”

Bulgaria initially agreed to hand over its Jewish population to the Nazis, and legislated severe curtailment of their rights, but at a late stage defied its ally by claiming that the Jews were needed for (forced) employment within their home country.

Mr Georgieff asked rhetorically: “Who is to take the credit for the unprecedented rescue: the Communist Party, the Orthodox Church, the King, a bunch of forthright MPs who openly opposed the planned deportations, or the power of Bulgaria’s civil society?

“These questions generate other questions. If the Bulgarians were so good to their Jews during the war, why were there so few Jews left in the Bulgaria of the Warsaw Pact? What happened to their heritage, a remnant of at least 18 centuries of Jewish presence in these lands?”

He went on: “What remains of the Jewish material heritage? I found a mixed picture. Many synagogues are abandoned, many cemeteries are untended [one of his photos shows headstones daubed with Nazi graffiti]. Some synagogues have been converted into art galleries and village halls. These represent a distant echo of what Jewish life was like previously”

Mr Georgieff’s powerful illustrations – digital, but not manipulated — show alongside the disuse of facilities the positive sides of the life of the country’s drastically-reduced Jewish community.

The keynote image, used for the poster promoting the exhibition, shows the faithful celebrating the centenary of the huge Sofia synagogue, which was opened in 1909 to accommodate more than 1,000 worshippers, but these days hosts far fewer. Outside Sofia, the only functioning Jewish temple is in Plovdiv, built 1887. There is a photo of the former synagogue in Dobrich, a city 30 km inland from the Black Sea; and of a building in the Danube port town of Vidin in a much worse condition, having been at one stage converted into a warehouse.

After their rescue, most Bulgarian Jews in the late 1940s were enthusiastic about what they saw as the Promised Land. “Very few Jews remained in Bulgaria after 1949 because so many came to Israel.”

Anthony Georgieff had his first exhibition of photography at the age of 19, since when he has had more than 30, most recently including Strasbourg, London, Vienna, and in 2018 three showings of Take the High Road: Photography from Scotland.

His most recent books, published in 2018, are A Guide to Communist Bulgaria with Dimana Trankova; and A Shadow Journey: Elizabeth Kostova’s Bulgaria and Eastern Europe with Ms Trankova and Ms Kostova.

A Guide to Jewish Bulgaria with Ms Trankova came out in 2011. They published A Guide to Ottoman Bulgaria with Hristo Matanov as editor. For The Bulgarians he collaborated with Georgi Lozanov. Other titles include Hidden Treasures of Bulgaria, Thracian Bulgaria and Roman Bulgaria.

Mr Georgieff’s career included a spell in the early 2000s as editor-in-chief of the Bulgarian edition of Playboy. The magazine sold about 60,000 copies per month, ahead of any other monthly. He said at the time: “We propagate the kind of liberal attitude to life, which has become the trademark of Playboy-US. But we are based on local culture and tradition. There are no strict guidelines except for good taste.”

Interviewed in 2002 by Milena Dinkova of Sofia News Agency Novinite.com, he was asked: “What makes famous Bulgarian women want to be on the cover of the magazine?” He answered by quoting the model (and subsequent politician) Juliana Kuncheva, who fronted the first issue: “It [Playboy] has overturned my life. I feel much more feminine and in better shape. I am overwhelmed with job offers, and my relationship with Zhoro [her husband] has gone to new heights.”

On the opening night of the exhibition, Mr Georgieff was introduced by Miglena Rogacheva, assistant to the director of the Bulgarian Cultural Institute. Ms Rogacheva said that the Institute had been pleased to host an exhibition of his Hidden Treasures of Bulgaria two years previously, and she lauded his involvement in over a dozen books on the cultural heritage of Bulgaria.

The story of Bulgarian Jews, said Mr Georgieff, showed how “the whims of history influence the lives of ordinary people.”

He made a strong plea for his country to celebrate its diversity. “All kinds of people live in Bulgaria, and Bulgaria should be proud of that.”

The Jewish Bulgaria exhibition is organised by the Free Speech Foundation and the Bulgarian Cultural Institute in London, with support from the America for Bulgaria Foundation.

Jewish Bulgaria, photography by Anthony Georgieff, is at the Bulgarian Cultural Institute, 188 Queen’s Gate, London SW7.