Ribera: Art of Violence, the first UK exhibition of Baroque master

By James Brewer

Prepare for portrayals of pain: Dulwich Picture Gallery’s latest exhibition turns to a man who illustrated the everyday story of torture, retribution and martyrdom in 17th century Naples.

A procession of horrifyingly merciless works by the Spanish/Italian Baroque painter and printmaker Jusepe de Ribera (1591–1652), fills the darkened rooms.

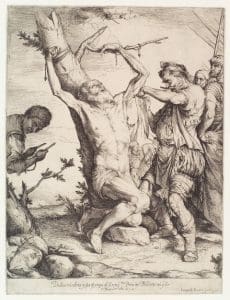

Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew, 1624. Miriam and Ira D Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

Ribera: Art of Violence, the first UK show assembling many of his most provocative works is not for the squeamish. The curatorial emphasis is on Ribera’s skilled draughtsmanship, his eloquent ‘language,’ as he moves between classicism and realism, but every image cuts to the quick.

It really does: the cutting of flesh is a prime gruesome motif. Ribera was known as a “pittore di terribilità” for his depictions of cruel punishments as part of documentary and admonitory convention in text and pictures. Judging by the awful detail recorded, he must have witnessed many a scene of administrative savagery.

His large paintings and rapid drawings were not for viewing by wimps or at the time presumably for women — as the fair sex is absent from the works shown here (apart from some beautiful training sketches of eyes, so fresh and round). Violence was in the fabric of society, and wielded by the elite, more openly than in most countries today. Torture and execution were punishments for both religious and civil crimes.

Ribera uses the violent subject matter to comment on the arts, on his own faith. It was a time when Catholicism was under threat from advances in science, and the Counter-Reformation was in full swing.

Studies of the Nose and Mouth, c 1622. Etching. © Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

Ribera, also known as lo Spagnoletto or ‘the little Spaniard’, was born in Játiva, Valencia, and spent most of his career in Naples, where he influenced Neapolitan masters including Salvator Rosa and Luca Giordano. He is often regarded as the heir to Caravaggio, to whom he owes a lot in the dramatic use of light and shadow, and practice of painting from live models.

The exhibition explores Ribera’s representations of subjects which are often grotesque but faithful to what was going on. It sets out, the curators say, to demonstrate how his images of bodies in pain are neither the product of his supposed sadism nor the expression of purely aesthetic interest. Rather, they involve a complex artistic, religious and cultural engagement in the depiction of bodily suffering. The messages are in turn sternly Christian and based on Greek and Roman mythology. Were these works for the Church or were they for intellectual debate?

Eight monumental canvases are displayed alongside drawings and prints. Co-curator Dr Xavier Bray, director of the Wallace Collection, said of the 40 works: “We found these pictures incredibly engaging.”

The layout examines Ribera’s striking depictions of saintly martyrdom and mythological violence, skin and the five senses, crime and punishment, and the bound male figure. The exhibition – seven years in the making — brings together works from seven countries and many are seen for the first time in the UK.

We are plunged straight away into an aura of religious violence, by being confronted with Ribera’s reverence for the martyrdom of St Bartholomew, who was said to have been flayed alive for his Christian faith. We are shown three versions of the martyrdom from various times in Ribera’s career, revealing the evolution of the artist’s style and his hyper-realistic treatment of a shocking theme.

Later there are anatomical studies, preparing for the contortions in human suffering as wrought by the strappado (punishment by hanging from the wrists). The viciousness reached beyond death: the corpses of the condemned were often subject to further abuse and humiliation.

A room dedicated to skin and the five senses includes outlines of eyes, ears, noses and mouths for young students of the time to copy. Before moving permanently to Naples in 1616, Ribera produced in Rome paintings representing the five senses. The sense of smell is personified as a beggar dressed in rags that peel away like the skin of an onion he has cracked open.

Ribera’s images rendering trauma and pain are variously considered repulsive and appealing. The twisted male body in such drawings as Man bound to a Treefrom the Musée du Louvre, Paris, finds its way into preparatory studies for paintings and prints, and more elaborate sketches and independent sheets.

In a glass case are tattooed pieces of real skin lent by the Science Museum of London. They were probably collected in France in the early 20th century and preserved as an anthropological curiosity because of the tattooing, which is said to be the oldest art form.

The grand finale is a room commanded by the 1637 oil on canvas Apollo and Marsyas, on loan from the Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples, on concession from the culture and tourism ministry. Paralleling the martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew, this painting – the tour de force of Ribera’s career – portrays Apollo flaying the satyr Marsyas as punishment for losing a musical contest. The flute of Marsyas was no match for the more versatile lyre of the god.

It is a warning to the ambitious, headstrong or politically rebellious against challenging the gods or the powers-that-be: it is the comedown for hubris. Here, we are told, is encapsulated the essence of the foregoing exhibits, with the visceral convergence of the senses, as the ripping of skin is portrayed through the intersections of sight, touch and sound.

With is music theme and the assault on the body of Marsyas, “this is a very loud painting,” said co-curator Dr Edward Payne, head curator of Spanish art for the Auckland Project, County Durham, This substantial painting may well have hung in a palace in Naples.

Dr Payne said: “Beyond merely introducing audiences to the work of this major artist, the exhibition will reveal the immediacy and complexity of Ribera’s images of violence. The show will call upon visitors to play a central role – not as passive onlookers but as active participants – in the theatre of Ribera’s scenes of human suffering.’

Remarking on Dulwich’s tradition of staging relatively small shows of great painters, Dr Bray added: “Ribera is not only the rightful heir to Caravaggio but will also, I am convinced, be of great inspiration to contemporary artists.”

Jennifer Scott, the Sackler Director of Dulwich Picture Gallery, described the potential visitor experience as “akin to witnessing a Quentin Tarantino film.”

Ribera: Art of Violence, is at Dulwich Picture Gallery until January 27, 2019.