Churchill: Walking with Destiny reviewed by a leading medical biographer

Churchill: Walking with Destiny, the new book by Andrew Roberts, is reviewed here by medical biographer Dr John H Mather.

By all accounts, Andrew Roberts has produced a study of Sir Winston Churchill that is worthy of the highest accolades. He assiduously sought out new sources of primary information and has clearly enhanced our understanding of what made him The Man of The 20th Century and the epitome of so many personal attributes of courage, insight, and fortitude. His reliance upon expert opinion is carefully sifted, which enhances his observations and conclusions about the impact of Churchill as a statesman, politician, painter, writer, a faithful loving husband, a somewhat indulgent family man, and his excruciating loyalty to his friends and trusted colleagues.

Roberts is always rigorous in quoting his sources and, in this regard, it was very gratifying to see his reference to me in relation to our communications on ‘Churchill’s health’. We certainly had a lot of discussions, mostly via email, of so much of what medically afflicted Churchill over his lifetime of 90 years. He has recorded accurately the many health and medical problems Churchill sustained and makes much of The Man’s resilience and hardiness, both physically and mentally. It might therefore be churlish on my part to cast any doubt on any of Robert’s conclusions as to Churchill’s health.

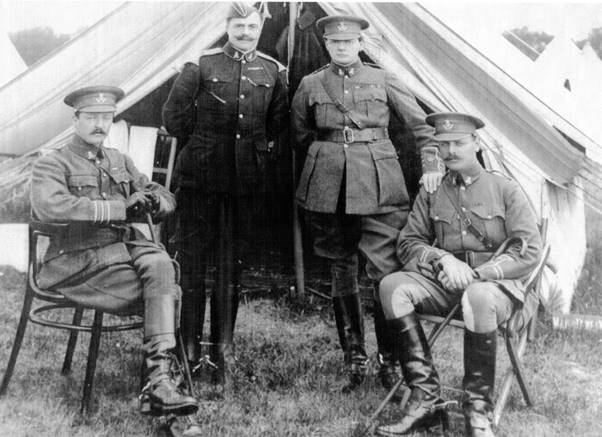

l tor: Colonel Charles Richard 9th Duke of Marlborough; Major Viscount Churchill; Major Winston Churchill; Major Jack Churchill, Oxfordshire Hussars.

Roberts cites two myths that prompt the format of this review: Churchill as an alcoholic and as a depressive.

There is ample medical evidence that Churchill was not a chronic alcoholic. The record shows that he was only actually ‘tiddly-poo’ once in his lifetime. This was in Moscow in August 1942, when Stalin plied both him and Anthony Eden (who followed him as Prime Minister), with shots of vodka when Stalin’s glass was only filled with water. Churchill and Eden left the Kremlin together and according to his military security detail, Sgt Manners, they refused the ride to their hotel in a Jeep but rather ‘wobbled’ down to their hotel arm-in-arm, very much the worse for an acute alcoholic intoxication.

Then there is the episode reported by Lord Alanbrooke where Churchill was observed to be ‘wobbly’ when woken up early into his afternoon nap for an emergent problem. Alanbrooke took this to mean that he had had too much alcoholic beverage at lunch while we now know that Churchill had taken a barbiturate (Phenobarbital) to be able to have a satisfactory undisturbed nap.

The recent movie Darkest Hour would have you believe that Churchill drank “straight whisky” most of every day. Not so, but certainly this was his reputation amongst Members of Parliament who wished him ill. The fact is he drank soda water-diluted glasses of Johnny Walker Red Whisky with only a ¼ inch of whisky in the bottom of a full glass and ice cubes.

It is interesting to reflect what this amount of whisky did to keep his coronary arteries to his heart relatively “clean” as he did not suffer a heart attack, notwithstanding Lord Moran’s assertions of December 1941. Although he had atherosclerosis of his arteries, the effect was on those to and in his brain, with transient ischemic attacks (analogous to angina of the heart) three strokes and dying after the last one. The coronary arteries are generally protected.

Regular moderate alcoholic intake tends to increase in the liver the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), and this is particularly applicable to men. Men are thereby able to more readily process their intake of alcoholic beverages while women are less fortunate as their liver ADH levels do not ‘improve’ with increased regular imbibing of alcoholic beverages. Churchill held forth in lengthy dinners at Chartwell and was never noted to be drunk.

Yet I demur when we designate Churchill’s depression as a myth. As a medical biographer I continue to examine this issue and my current conclusion is that he was a depressive to some extent, yet to be fully clarified as to frequency and depth or magnitude.

Early on in my inquiries I had a long and somewhat contentious discussion with his late daughter, Mary the Lady Soames. She was quite certain that her father was only depressed when he had adverse news about the setbacks during World War Two as was the case in early 1942. She specifically claimed that her father picked up the term “black dog,” a commonplace description by Victorian nannies for out-of-sorts children, from his old nurse, Mrs Everest. It was not until she saw her father’s letter to his wife Clementine in July 1911, when he used the term ‘black dog’ that Mary accepted the possibility of the Black Dog afflicting her father. Later on, she stated that her father’s ‘Black Dog’ was ameliorated by his painting and his close family support as in her Forward to the book of her father’s paintings published in 2003 by David Coombs with Minnie Churchill, .

Again, for the medical biographer it is always treacherous to declare certain symptoms and signs as attributable to a certain diagnosis after many decades have passed.

The symptoms of a mental condition may be discounted if the focus of a physician’s education has not included a deep study of what psychiatrists do to make a diagnosis of depression or other mental disabling impairments such as an anxiety syndrome bordering on panic. Also, the discipline of mental health (the realm of the psychiatrist) has changed its definitions of depression, neuroses and psychoses over the course of several decades. This is besides the indiscriminate ‘lay’ use of the designation of depression. This only serves to confuse an understanding of whether there is a perception of an individual as “out of sorts” or something more significant such as a “fugue” state of doing nothing or just sleeping a lot of the time and skipping meals. The term ‘melancholia’ is not a medical descriptor but was used a lot in earlier descriptions of an individual’s mood.

Mary Soames initially said that the first psychiatrist to actually ‘put it out there’, Dr Anthony Storr, in a 1969 essay that appeared in the book Churchill: Four Faces and the Man, had never examined her father. Subsequent commentators on Churchill’s Black Dog have taken their cue from Dr Storr and the ten or so references, some referred to as ‘black moods’, by Lord Moran in his 1966 book, Winston Churchill, The Struggle for Survival, 1940-1965. These two authors have apparently confounded the matter of reaching a clear and irrefutable conclusion as to the existence and essence of the Black Dog by medical practitioners.

Eventually, someone, erudite and especially adept at synthesizing all aspects of Churchill’s personality into a complete “picture” that includes a full analysis of his mental health and parses out the different contributions to the essential Churchill, will write a definitive account.

It was his early biographer, Sir Martin Gilbert’s conclusion, that Churchill’s melancholic occurrences were brief, never disabling, and usually a reaction to personal misfortune and thwarted ambition, with one caveat, his depression was obviously manifest in his last five years. This could have been a concurrent morbidity (actually a ‘false’ depression) associated with Churchill’s progressive vascular dementia, not Alzheimer’s Disease as others have also claimed. A deep untreated depression in an elderly person may present as a pseudo dementia which lifts with suitable antidepressants..

If accepted inter alia that Churchill was vulnerable to a mild depression compounded by worry and anxiety, we need to acknowledge that anxiety is a common co-morbid condition of depression. Further, other potential co-morbid issues such as alcohol intake, strange sleep patterns and use of amphetamine stimulants beginning during World War II, might affect reaching an appropriate overall conclusive diagnosis. Certainly, Lord Moran provided (maybe prescribed) such a variety of uppers (amphetamines) and downers (Phenobarbital) that Churchill kept them in a pill box and sometimes he took them as he, Churchill, saw fit.

Lord Moran in his book records several conversations with Churchill and the ‘Black Dog’, and a metaphor for depression, emerges. Lord Moran was not well versed in the management of any mental impairment and certainly did not refer Churchill to any other physician, especially a psychiatrist whom Churchill abhorred. Further, Lord Moran does not discuss depression along with a basic anxiety and does not iterate other possible levels of depression.

When I interviewed Sir Anthony Montague-Brown in 1997, he said that Churchill would, on a gloomy and overcast day in London, say, “Let’s go and find the sunshine” which meant they promptly set off for the South of France to be at La Pausa or La Capponcina. The sunshine would alleviate his apparent SAD (Seasonal Affective Disorder) syndrome with the intense sunlight. There, he could also indulge in his hobby of painting landscapes, which so absorbed him and took away his anxieties. Churchill noted himself that painting was a fine antidote to his predisposition to dwell on the dark side.

Perhaps one of the more intriguing aspects of Roberts’s book is an absence of explaining Churchill’s mood disorders. His son Randolph discussed with Dr Fieve, a psychiatrist, the frequency and range of Churchill’s mood swings in the 1975 book Moodswing. Others, including Brendon Bracken and Lord Ismay, have also commented elsewhere on Churchill’s dramatic changes in mood, not always associated with any particular external event. This aspect of Churchill’s demeanour resulted in Dr Brain, Churchill’s neurologist, concluding that Churchill had a cyclothymic personality which may today be labelled as a minor variant of a Type II bipolar disorder. Unfortunately Dr Brain’s conclusion appears to be less of a personal observation but that told him by Lord Moran as recorded in his article Encounters with Winston Churchill. Medical History, 2000.

I can find no passing reference by Roberts to other authors who have concluded that Churchill’s ‘bi-polar’ personality turned out to be a big plus in his selection as Prime Minister in 1940, and conduct of World War II. Two books, by Dr Nassir Ghaemi, Out of the Wilderness Churchill. A First-rate Madness 2011 and Andrew Norman’s Winston Churchill. Portrait of an Unquiet Mind 2012 have put forth this thesis. They conclude that, in the early part of World War II, Churchill’s indomitable mental resilience and courage was only possible because of a hypomania that drove him to a heavy work schedule, which often exhausted his Generals and the War Cabinet. This is somewhat speculative as a mood swing can simply be a depression without a hypomania. Churchill was well rested after a night’s sleep (3 to 4 hours) and afternoon naps (as much as 2 hours) that he was able to pack two days’ work into a 24 hour period, or so he claimed.

A much more complicated picture emerges if the full record of events is examined and the mood swings are placed in a broader context, with the recognition of a possibly mild to flagrant (clinically diagnosable) depression. Many have mood swings; sometimes related to external events and some physiologic, such as a low testosterone that surely Churchill had in later life. An instant recovery may come as a result of alleviation of the external stressor or treatment of the hormone deficit. Then, a family history of ‘melancholia’, as has been shown to be present as far back as the First Duke of Marlborough, needs to be considered as an underlying familial factor.

So what are we to think about Churchill’s Black Dog? Churchill definitely had mood swings with ‘melancholic’ episodes (the blues). It was Mary Soames who made the assessment that the Black Dog was usually ‘kennelled’, except when there was news of devastating reverses in battles, and that her father was able to better alleviate its occurrences and severity with his absorption with painting and a devoted loving wife and family. She does not deny that her father had periods of depression, the Black Dog, but asserts that her father was able to effectively deal with it and not let it seriously affect his performance as a warrior and statesman. I heartily agree.

Churchill Walking with Destiny is published by Allen Lane Penguin Books, price £35.

Renowned medical biographer Dr John H Mather MD FACPE has been active in the International Churchill Society and is a past president of the Churchill Society of Tennessee, currently serving as its archivist-historian.