Picasso and Paper exhibition unfolds its allure at the Royal Academy in London

By James Brewer

Pablo Picasso is famed for his blue, rose and African periods and his multi-decade compulsion for Cubism – but even more fundamental was what might be called his life-long ‘paper period.’

Underpinning his outpouring of 20,000 works, many of which redefined painting, sculpture, printmaking and design for the 20th century, can be traced his imaginative and inventive use of paper, argues the Royal Academy of Arts as it opens Picasso and Paper, said to be the most comprehensive exhibition to date on this proposition.

It is a show that majors on his artistry rather than his tumultuous personal relationships, valuably enabling visitors to assess his oeuvre from start to finish.

While Picasso exhibitions “every five minutes” in recent times have focused on assorted aspects of his life, the theme of his creativity through the medium of paper “gives us the opportunity to look at his entire career, from when he was a seven-year-old boy,” said Royal Academy chief executive Axel Rüger as he introduced the milestone event. This route gives us personal access to the artist’s mind, insisted the RA chief. “Many of these works have never been seen and being fragile will not be seen very often.”

It is true that Picasso exhibitions are big box office: Tate Modern’s 2018 venture entitled Picasso 1932: Love, Fame, Tragedy, helped that gallery become the UK’s most popular museum of the year.

Now, with 300 exhibits, the RA takes us accessibly through the staging posts of Picasso’s 80 years of artistic practice, with his recurring motifs of the female form (in poses provocative and demure, depicted variously in figurative, abstract and Cubist manner), still life, and the Minotaur and bullfighting.

Although less renowned than his friend and rival Matisse for his flair with paper, Picasso is remarkable for the sheer variety he used in the studio. To name but some, said Royal Academy curator Ann Dumas, there was antique paper, wrapping paper, wallpaper, napkins, newspaper, cardboard and hotel notepaper.

He was forever drawing, using watercolour, pastel and gouache, on whatever kind of paper was to hand, and even created sculptures from pieces of torn and burnt paper.

This paraphernalia, if you want to call it that, was a measure of the man. Anyone who finds Picasso’s famed Cubist deconstructions a turn-off will see paper as the starting point of a myriad examples of compelling draughtsmanship. Here are included vivacious compositions that attract with their relative conventionality, but all are the product of a fertile mind. He remained a master of immediacy in presentation, decked with his uninhibited experimentation and eroticism.

Whether it is true that the first words the boy – born in Malaga in 1881 – spoke were to ask for a pencil, at the age of seven he was learning diligently from his painter and drawing teacher father and soon could skilfully portray on paper a life model. He would say later in life: “All children are artists. The problem is how to remain an artist once he grows up.”

After studying at art school in Barcelona, he moved to Paris with his close friend, fellow art student Carlos Casagemas who was to commit suicide at the age of 20 over disappointment in love. A few paces after entering the exhibition, the visitor is confronted by Picasso’s masterpiece of the Blue Period, La Vie from 1903 (courtesy of Cleveland Museum of Art), painted in response to the tragic death of Carlos.

At this point, the strategy of the exhibition is evident, as La Vie is displayed close to preparatory drawings and other works on paper exploring poverty, despair and social alienation.

The artist’s key turning point is represented by a reproduction of the large work Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (the original is in the New York Museum of Modern Art). The 1907 oil on canvas, thrusting to the fore five naked female prostitutes, scandalised sections of society. It essentially reflects what is known as Picasso’s African Period when his output was influenced by the sculpture and masks of the continent, seen in the enigmatic faces and distorted bodies of the women. Their geometric form underlines their confrontational manner and paves the way for the raw sexuality that was to cascade from the palette of the emergent new Picasso.

In the year of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon Picasso had met Georges Braque, and the two waded forth into a new language – a style that fragments objects as if seen simultaneously from different perspectives. Breaking up natural forms into angular shapes meant that cut and pasted papers were pivotal in the evolution of Cubism.

This large proto-Cubist work Les Demoiselles took nine months to complete amid parallel ferment internationally in music, literature and politics, although it would be another 30 years before Picasso turned to a directly political subject, commissioned by Spain’s Republican government and stirred by the aerial bombardment of Guernica.

Musée national Picasso-Paris has lent to the RA studies for Les Demoiselles d’Avignon including the ambiguously titled Bust of Woman or Sailor. Several other collage pieces with applied newsprint are lent by the Paris museum including representations of a violin and of guitars, from 1912.

One notable episode was Picasso’s involvement in 1917 designing costumes and sets for the ballet Parade, a one-act theatre piece by Jean Cocteau for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. The staging was a constellation of many illustrious names: choreography by Léonide Massine, music by Erik Satie, and orchestra conducted by Ernest Ansermet. Wartime chaos meant that except for Satie, the principal artists met in Rome to begin work, ahead of the premiere on May 18, 1917 at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris. Picasso’s costumes were large fantastical creations in cardboard – one is reproduced in the gallery and there is film footage of a more recent performance – which were difficult for the protagonists to dance in.

Cocteau was inspired to produce the ballet after hearing Satie’s Trois morceaux en forme de poire (Three Pieces in the Shape of a Pear). Satie had never previously written a ballet score, and in the end thanks to Cocteau it included as instruments typewriter, klaxon, milk bottles and pistol. Possibly Cocteau wanted to create a succès de scandale comparable to that of Igor Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps which had been premiered in the French capital in 1913.

Picasso was attracted by the myth of the Minotaur, a half-man half-bull monster from Greek mythology, which he saw as a personification of his strength and masculinity. His interest grew out of the ritualistic significance of the bull in Spanish culture. His first depiction of the beast appears in a 2 m wide collage of blue and beige pasted papers completed in 1928.

The reputed ability of the Minotaur to overpower women is vivid in many of his compositions where figures resemble his partners: Olga Khokhlova, Marie-Thérèse Walter and Dora Maar. The physical battles he depicts could be considered to symbolise the psychological tensions within these intertwined relationships, say the curators.

There are nine Minotaur works here, probably more than half of the number of such pieces executed in the 1930s. One savage example shows the Minotaur ravaging Dora.

Dora Maar, subject of a fascinating exhibition that has been running at Tate Modern, was on hand to capture with her camera the work in progress of Picasso’s Guernica, an immense mural completed in just a month and a half. Some critics have speculated that the bull painted on the left side of the canvas, lacking emotional expression, is an emblem of General Franco or of fascism, but Picasso never confirmed that. There is a suggestion of torn newsprint in the painting, perhaps because it was from a newspaper article that Picasso learned details of the bombing of the town.

Broadly chronological, the exhibition romps through Picasso’s career. Highlights include Women at Their Toilette, from winter 1937-38 (Musée national Picasso-Paris) an extraordinary 4.5 m long collage of cut and pasted papers, restored in 2018 and exhibited in the UK for the first time in more than half a century. Framing the images of Olga, Marie-Thérèse and Dora, Picasso returns to a very large format and assembles a multitude of paper cut-outs with varied motifs.

Dora is the subject of his excursions into his next levels of Cubism – for instance Seated Woman (Dora) from 1938 (Fondation Beyeler).

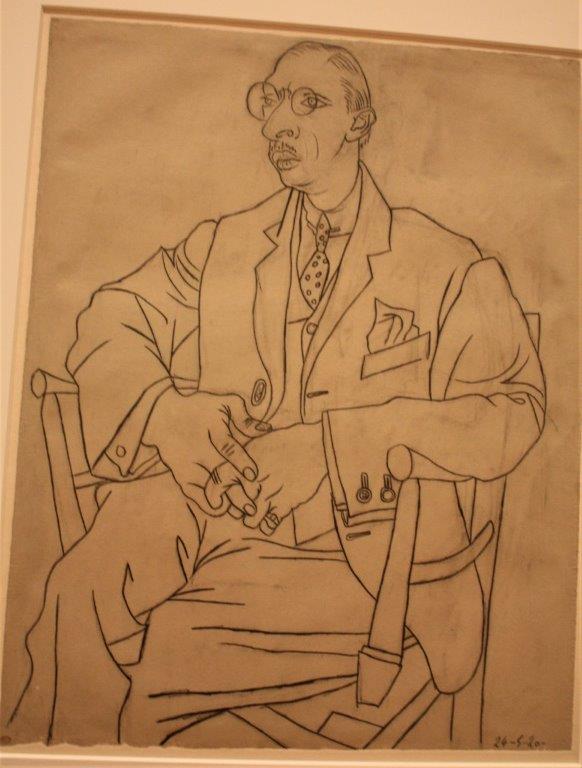

In drawings such as the portrait of Stravinsky, dated 24 May 1920, made in Rome with pencil and charcoal on laid paper, Picasso showed his skill at caricature. Stravinsky relates in Chronicle of My Life that when the military at the Swiss border town of Chiasso found the drawing in his luggage, they refused to believe it was his portrait drawn by a distinguished artist and suspected it of being of sinister significance. Stravinsky had to have the portrait sent to the British Ambassador in Rome, who later forwarded it to Paris in the diplomatic bag. The delay made Stravinsky miss his connection, and he had to spend the night at Chiasso.

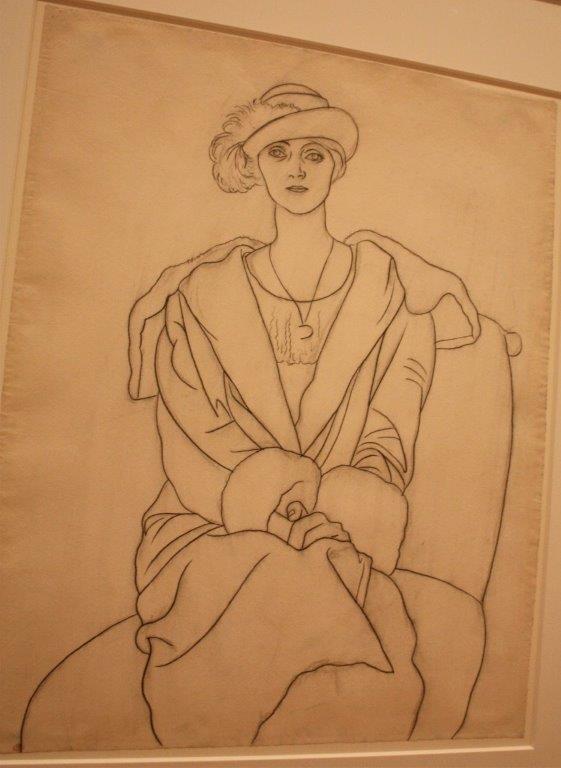

From the same time in pencil and charcoal on high quality wove paper is a more sympathetic post-impressionist portrait – Olga with a Feathered Hat. Further drawings include Self-portrait, 1918 (Musée national Picasso-Paris).

The drawings are shown alongside examples of the many printing techniques he used – etching, drypoint, engraving, aquatint, lithograph and linocut. Some of his hundreds of sketchbooks are on view. Even his printing press is here.

An early girlfriend of a seven-year relationship – the artist, model and writer Fernande Olivier – was the subject of Picasso’s Cubist bronze Head of a Woman (Fernande) 1909 (Musée national Picasso-Paris) which is exhibited with associated drawings. A monumental sculpture of the war years, Man with a Sheep, 1943 (Musée national Picasso-Paris), is displayed alongside large ink and wash drawings.

The film Le Mystère Picasso of 1955, a compelling documentary showing the maestro drawing with felt-tip pens on blank newsprint, as the camera team urge him to hurry before their supply of celluloid runs out, gives insights into his working methods and contrarian creativity. It is shown on large screen, with on the nearby walls original drawings made for the production.

The closing section focuses on Picasso’s last decade which saw him as prolific as ever in his drawing, and unstoppable, particularly as a printmaker. Head of a Woman was made sparely in pencil on cut and folded paper in the French fishing village of Mougins, where he spent the last 12 years of his life. This work, held by the Musée national Picasso-Paris, is chosen by the RA and partner museums for the exhibition poster.

The exhibition is a collaboration between the Royal Academy, Cleveland Museum of Art and Musée national Picasso-Paris (from where most of the loans come). It is curated by Ann Dumas for the London academy, William Robinson for the Cleveland museum and Emilia Philippot for the Paris institution.

Captions in detail:

Pablo Picasso drawing in Antibes, summer 1946. Photo © Michel Sima/Bridgeman Images. © Succession Picasso/DACS 2019.

Femmes à leur toilette, Paris, winter 1937–38. Collage of cut-out wallpapers with gouache on paper pasted onto canvas. Musée national Picasso-Paris. Pablo Picasso Gift in Lieu, 1979. MP176.Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris)/Adrien Didierjean. © Succession Picasso/DACS 2019.

Self-portrait, 1918. Pencil and charcoal on wove paper. Musée national Picasso-Paris. Pablo Picasso gift in lieu, 1979. MP794. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris)/Mathieu Rabeau. © Succession Picasso/DACS 2019.

Violin, Paris, autumn 1912. Laid paper, wallpaper, newspaper, wove wrapping paper and glazed black wove paper, cut and pasted onto cardboard, with pencil and charcoal. Musée national Picasso-Paris. Pablo Picasso Gift in Lieu, 1979. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris)/ Mathieu Rabeau. © Succession Picasso/DACS 2019.

Seated Woman (Dora), 1938. Ink, gouache and coloured chalk on paper. Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection. Photo: Peter Schibli. © Succession Picasso/DACS 2019.

Bust of Woman or Sailor (Study for Les Demoiselles d’Avignon), Paris, spring 1907. Oil on cardboard.

Musée national Picasso-Paris. Pablo Picasso gift in lieu, 1979. MP15. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris)/Adrien Didierjean. © Succession Picasso/DACS 2019.

Olga with a Feathered Hat. 1920. Pencil and charcoal on Whatman wove paper. Musée national Picasso-Paris. Pablo Picasso Gift in Lieu, 1979.

Portrait of Igor Stravinsky. 24 May 1920. Pencil and charcoal on laid paper. Musée national Picasso-Paris. Pablo Picasso Gift in Lieu, 1979.

Minotaur. 1933. Charcoal on wove paper. Musée national Picasso-Paris. Pablo Picasso Gift in Lieu, 1979.

Royal Academy poster featuring Head of a Woman, Mougins, 4 December 1962. Pencil on cut and folded wove paper.

Picasso and Paper is in the main galleries of the Royal Academy of Arts, London, until April 13, 2020.