GSCC Annual Report 2020 – 2021

Greek Shipping Co-operation Committee

We begin with the Chairman’s Message:

Dear Colleagues,

It is with great pleasure that I present our 86th annual report in 2021.

It has been a tumultuous year because over the last 12 months the world has faced the greatest pandemic since the last one over 100 years ago, this has resulted in a huge loss of life and dislocated the normality of our everyday existence.

However, during this period, doctors, nurses, scientists have valiantly fought both to aid those who are suffering and to create a myriad of vaccines that have begun to overcome this appalling event.

In the meantime, the unsung heroes of our maritime industry, the seafarers at sea and the shore staff looking after them have continued doing their job invisibly and selflessly, ensuring that world trade is not disrupted and that all the essential goods arrive at their destination, and on time without any visible dislocation.

This is despite the fact that neither Governments nor regulators have done enough to recognize the importance of seafarers by considering them as essential or key workers and afforded them priority inoculation or allowed them to easily embark or disembark from vessels around the world. Equally disappointing is the prohibition of seafarers by some nations to have shore access for health and medical reasons.

Too few countries or ports allow a safe haven for seafarers to sign on or off ships and there is little stability in where and when crews can change hoping that in return Governments will show flexibility in the amount of time crews will remain aboard vessels.

Fortunately, as the pandemic is hopefully receding, world trade is beginning to recover, mainly through Government stimulus programmes and the economic benefits they bring about and in turn business optimism is returning. Against that, there is the perception that we may bring about an inflationary period which could have far reaching effects.

This is certainly evident in the container sector where freights are reaching historically high levels as vessel imbalances are causing shipping lines to scramble to secure any available tonnage, at whatever price.

The dry bulk sector has also seen some improvement over the last six months. Not as dramatic as the container ship sector, but enough to bring about a more positive feeling.

Tankers unfortunately have not yet recovered and are still at depressingly low levels, especially for the larger vessels.

However, the Gas Carriers have seen better days perhaps due to the perception of the clean element of their energy cargoes.

The car carrier sector has also come back to life on the back of greater global demand for new and second-hand cars.

Against this background, the Greek shipping industry has cemented its position as the world’s largest fleet and has increased its market share in most sectors. This has been achieved through a combination of newbuilding deliveries and strategic second-hand purchases.

The Greek fleet is getting younger compared to the average world fleet age, bigger, more technically sophisticated in its fuelling systems for newbuildings, and has acquired a significant amount of very modern second-hand ships including about half a dozen cruise ships.

At the same time, it has disposed of a large amount of older, less energy efficient smaller vessels through second hand sales and recycling facilities. Whether we are talking about crude or clean Tankers, LNG and LPG Carriers, Container ships and Car Carriers, Bulk Carriers, the market share of the Greek fleet is growing annually.

As a result of the above, the Greek fleet is continually reducing its carbon footprint and proving that the deep-sea shipping industry is by far the most energy efficient form of transportation for the movement of any bulk or unitised commodity. On a per ton basis, shipping is continually raising the bar in the way that it maximises its efficiency and has shown a continuous improvement over the last 40 years.

Over the last 12 months, the G.S.C.C. has ceaselessly continued its task in lobbying at the highest levels. Firstly, to improve the lot of seafarers due to COVID-19 and secondly, to give the benefit of its experience and knowledge to all the relevant organizations and Governments to bring about workable maritime solutions to all the problems and issues we face.

Below, we mention but a few of the most current issues.

A. 2030/2050

Decarbonization, or the total reduction of greenhouse gases is a paramount objective of the G.S.C.C. as we work towards 2050. However, it is imperative that we create workable, safe, maritime solutions to this critical issue and we involve those whose primary responsibility it is, namely shipbuilders, engine builders, fuel suppliers and charterers.

So far, all of the above have been notable for their silence and the lack of any technical breakthrough that can bring about an industry wide solution.

At present we have the possibility of at least half a dozen different alternative fuels, none of which really provide a safe and greener footprint than what already exists today. Decarbonization progress must go hand in hand with the safety of seafarers, vessels and cargoes.

We have no new powerplant solutions yet and shipbuilders will not build hydrodynamically more energy efficient vessels because charterers do not want a real green solution. So, the result is a large number of very small improvements which, whilst positive, will not bring us the breakthrough we all wish for.

It is imperative that any global solution to our decarbonization happens through the I.M.O and not some regional bodies which cannot have the experience that the I.M.O. possesses.

B. Robust Ships

People cannot truly espouse E.S.G. policies if they do not realize that robust, well-built ships are imperative to protect the environment and the safety of all those who serve on board the global fleet.

It is inconceivable that in this era we still have ships that are virtually new suffering hull and machinery failures due to low standards of construction and safety levels. The examples of virtually new Ore Carriers nearly sinking are unacceptable and could easily be rectified with higher standards of construction and safety.

C. Maritime Training

A national and international issue but as it pertains to the Greek fleet it is still imperative to increase the quantity and quality of educational establishments in Greece including private schools and academies. Without a constant flow of Greek seafarers, the link between Greece and its shipping industry will inevitably weaken.

One of the greatest strengths of the Greek shipping industry over the last half century has been the close relationship between the Greek shipping industry and the Ministry of Mercantile Marine, the Hellenic Coast Guard and of course the Government itself, irrespective of political leanings. Without the appreciation of how strong this link is, the Greek maritime cluster would not be as prominent as it is and the position of shipping as Greece’s second most important export industry. This link must be maintained going forward in order to guarantee a vibrant maritime sector.

Apart from its close and warm links with the Union of Greek Ship Owners in Greece, the G.S.C.C. prides itself on maintaining a close dialogue with all major international maritime organizations such as the I.M.O, ICS, INTERCARGO, INTERTANKO, RightShip, BIMCO, the EU, national Governments, MEPs, and the International Group of P&I Clubs, having Club Chairmen and Directors on our Council.

Our relationship with the senior IACS members is also very close, not least due to our presence as individual members on the boards of many National and International Committees of leading Classification Societies. We also work together with them in pressing for ever higher vessel standards in construction and operation.

Being based in London, gives us the opportunity to keep in close contact with the Baltic Exchange (the world’s leading shipping indices provider), the UK Chamber of Shipping, Maritime London, and other London-based organizations. We also support the aims of London International Shipping Week in reminding our global shipping community of the importance of the U.K. and London in particular.

I would like to mention with great sadness the loss of one of our most respected and admired Council Members, John A. Angelicoussis. John served on the Council of the G.S.C.C. for over two decades and epitomised all that is great about Greek shipping. His company has grown into the largest Greek shipping group with a very substantial fleet of L.N.G. Carriers, Tankers and Bulk Carriers. Apart from the fact that virtually all the ships have been contracted as newbuildings for the Group, the ships have been constructed to the highest standards, mainly fly the Greek flag and have a very substantial number of Greek seafarers on board. In addition to all the above, John was a great patriot who supported many philanthropic causes within Greece, doing all of this whilst not advertising the fact.

John’s passing away leaves a great void to Greek shipping but an admirable example to us all. He is succeeded by his very capable daughter Maria.

Finally, I would like to thank our Member Offices for their support, the Council and the Secretariat for their hard work, which allows us to continue keeping our membership well-informed and lobby on a global basis in favour of positive practical legislation and where this is negative, to make our opinion very well-known, backing it up with well-reasoned arguments.

I am particularly grateful to our Vice-Chairmen, Constantinos Caroussis, John M. Lyras and Spyros Polemis, our Honorary Chairman Epaminondas Embiricos, our Treasurer Diamantis Lemos and Deputy Treasurer Dimitri Frank Saracakis.

My special thanks go to Stathes Kulukundis and his team John Hadjipateras, George Embiricos, Filippos Lemos, Alex Hadjipateras and Basil Mavroleon, without whom our monthly reports and other documents would not be as professionally prepared as they are. My thanks also go to Thimios Mitropoulos for his invaluable knowledge on international legislation, and for keeping his eagle eye on our Council minutes.

Our Director Konstantinos Amarantidis, ably assisted by Maria Syllignaki, continue to run the Committee smoothly and very professionally, and I thank them for their sterling efforts.

But yet again this year I wish to thank all the seafarers in the world, whose perseverance during this difficult period has been legendary and without whom world seaborne trade would not be able to take place.

Table of Contents

From the Chairman 3

Fleet Statistics 9

The World Fleet 9

The Greek Controlled Fleet 9

Developments in Greece 11

Economic Outlook 11

COVID-19 12

Milestone 200 Anniversary of Greek Independence 13

Maritime Affairs 14

Ongoing Tensions in the Aegean and Migrant Issues 15

Developments in the UK 17

Economic Outlook 17

COVID-19 19

New UK Maritime Minister 20

Brexit 21

COVID-19 Pandemic – Impact on International Shipping 22

IMO Decarbonisation Roadmap 26

Background 26

New Requirements 29

Newbuilds – EEDI 29

Existing Ships – EEXI 30

EEXI Compliance Steps 32

New and Existing ships – CII 33

CII Compliance Steps 35

The Road Ahead – An Unknown Future 36

EU Environmental Proposal & Other National Schemes 38

Cyber Security 43

IMO Guidelines 44

United States Coast Guard (USCG) Guidelines 45

Piracy 49

Overview 49

West Africa 53

East Africa 56

South America 58

Asia 59

Ship Recycling 61

Recent Activity 61

Regulatory Developments 62

EU SRR 62

IMO HKC 64

Progress Towards Safer Recycling Practices 65

Shipbuilding 68

Yard Outlook 70

US Sanctions Against Iran 72

US Sanctions Against Venezuela 75

Panama Canal 79

Suez Canal 84

Ongoing Mediterranean Migrant Crisis 87

| G.S.C.C. Council Members | |

| Mr. Haralambos J. Fafalios | Chairman |

| Mr. Constantinos I. Caroussis | Vice Chairman |

| Mr. John M. Lyras | Vice Chairman |

| Mr. Spyros M. Polemis | Vice Chairman |

| Mr. Diamantis J. Lemos | Treasurer |

| Mr. Dimitri Frank Saracakis | Deputy Treasurer |

| Mr. John A. Angelicoussis | Member |

| Mr. Dimitri C. Dragazis | Member |

| Mr. George E. Embiricos | Member |

| Mr. Alexandros J. Hadjipateras | Member |

| Mr. John M. Hadjipateras | Member |

| Mr. Antonios C. Kanellakis | Member |

| Mr. Alexandros C. Kedros | Member |

| Mr. Stathes J. Kulukundis | Member |

| Mr. Filippos P. N. Lemos | Member |

| Mr. Basil E. Mavroleon | Member |

| Mr. Efthymios E. Mitropoulos | Member |

| Mr. Anthony P. Palios | Member |

| Mr. Michael G. Pateras | Member |

| Mr. Andreas A. Tsavliris | Member |

| Mr. Epaminondas Embiricos | Honorary Chairman |

| G.S.C.C. Secretariat | |

| Mr. Konstantinos Amarantidis | Director |

| Ms Maria Syllignaki | Assistant Director |

Fleet Statistics

The World Fleet

As of 10 March 2021, according to IHS data, the world fleet of self-propelled, sea-going merchant ships, greater than 1,000 Gross Tons (GT), stood at 57,054 vessels of 1,544,687,201 GT, including 3,407 vessels of 128,339,808 GT on order.

The Greek Controlled Fleet

As the aforementioned IHS data suggest, as of 10 March 2021, Greek interests controlled 4,038 vessels of various categories of 350,465,999 total deadweight (DWT), and 205,647,569 total GT. Compared to the data of the previous year, this represents an increase of 70 vessels, 9,642,362 DWT and 5,953,710 GT. These figures include 134 vessels of various categories, of 17,814,560 DWT and 11,480,103 GT, which are on order. In view of the unstable market conditions experienced during the period and COVID-19 the pandemic, the increase in the number of vessels, GT and DWT is encouraging.

With respect to vessel type, the Greek owned fleet recorded a slight decline in the categories of Oil Tankers, Liquefied Gas Carriers and Passenger vessels in terms of vessel numbers and DWT.

Chemical & Products Tankers and Other Cargo Ships also recorded a slight decrease in DWT, while vessel numbers remained the same. On the other hand, Ore & Bulk Carriers, Container Ships and Cargo Ships presented a slight increase both in DWT and number of ships in relation to the corresponding world fleet statistics for the year 2019, in terms of vessel numbers /2020.

What is notable is that, in terms of vessel numbers, Greek parent companies represent 26,5% of the world tanker fleet and 14.9% of the Ore and Bulk fleet.

Overall, the Greek owned fleet stands at 7.1% of the global fleet in terms of number of vessels, 13.3% in terms of GT and 15.8% in terms of DWT.

According to the data, the past year saw an increase in the average age of the world fleet, from 14.1 years in 2019/2020, to 14.5 in 2020/2021. However, the average Greek-controlled vessel, at 12.1 years of age, is 2.4 years younger than the industry average. When calculated in terms of GT and DWT, the average age is reduced to just 10.3 and 10.2 years, respectively, as against 10.5 and 10.2 of the world fleet.

The fleet registered under the Greek flag, as a percentage of the world fleet, in terms of number of ships, GT, and DWT is 1, 2.4 and 2.8 respectively. It should be noted, however, that for oil tankers the percentages are 6.9, 7.3 and 7.4 respectively.

The Greek registered fleet has decreased in terms of vessel numbers as well as DWT and GT, now comprising 586 ships of 36,623,355 GT and 62,317,858 DWT. The significant decrease in the number of vessels registered under the Greek flag should be taken into consideration by the Greek administration.

(Source: IHS Markit)

Developments in Greece

Economic Outlook

The previously optimistic macroeconomic projections for 2020 for Greece overturned as the COVID-19 pandemic significantly affected economic activity, thus driving the country’s economy into a deep recession and threatening financial stability.

The Greek economy, highly dependent on services, with a high share of tourism and retail trade in its GDP, was hit harder than other EU countries by the shocks to external and domestic demand. In 2020, the recession reached 8.2%. Tourism revenues shrunk as international arrivals decreased by 76.5 % in 2020, with the country welcoming only 7.4 million visitors, compared to 34 million in 2019.

The fiscal support measures and the recession led to a sharp reversal of the general government primary budget surplus into a deficit in 2020 and, combined with a substantial drop in nominal output, to a significant increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio. Revised projections by the Bank of Greece place the 2020 general government primary budget deficit at 7.0% of GDP, and public debt at 205% of GDP.

As uncertainty remained elevated, fiscal policy for 2021 has been complemented with new expansionary measures, which will further weigh on the fiscal balance. The general government primary deficit in 2021 is projected to reach 5.3% of GDP.

The rebound of demand is projected to pick up later in 2021, specifically from the second quarter onwards, leading the Greek economy to strong positive growth. According to Bank of Greece, the real GDP growth rate in 2021 is forecast at 4.2%. This, however, is subject to uncertainty due to risks associated with the epidemiological developments.

In 2022, the recovery is projected to accelerate, as the virus is expected to be better controlled, with the vaccines having become more generally deployed, restrictions being eased globally and the government implementing new investment projects.

COVID-19

While the health impact of the first wave of COVID-19 was very limited in Greece, from late summer 2020 daily infections, hospitalisations and mortality begun rising exponentially, yet remaining below the EU average.

Responding to the rising second wave, a new round of lockdown and containment measures were introduced in early November 2020. The Greek government initially introduced the requirement of wearing masks in public spaces, then reintroduced strict nationwide movement restrictions, and closed businesses with high levels of physical interaction, as well as schools and nurseries.

Despite the restrictions, the country experienced periodic surges of the pandemic, with measures being further tightened in mid-February and again in early March 2021. Compared with the ones imposed during the first wave, the subsequent containment measures were less strict, as evidenced by relatively higher citizen mobility and by continued industrial and construction activities.

Looking at the country’s death toll from COVID-19 since the outbreak of the pandemic, as of 6 June 2021, the number of fatalities stood at 12.277, with 95.2% reported to have an underlying condition and aged 70 or more, according to the National Public Health Organization (ΕΟΔΥ).

On a more positive note, the vaccination programme across Greece has noted good progress, with more than 21% of the country’s population vaccinated as of 5 June 2021, a total of 6.084.963 doses of COVID vaccines administered, and 2.305.626 full vaccinations achieved.

Small Greek islands, with a population of less than 1,000 residents, have been prioritised for COVID-19 vaccination. A number of small islands including Oinousses, Chalki, Symi and Kastellorizzo, have already had their entire adult population vaccinated. The remaining Greek islands, excluding Crete, have also been prioritised in the national COVID-19 vaccination programme, with the aim of fully vaccinating all adult population by the end of June.

Greek seafarers have also been prioritised for COVID-19 vaccination, with the Ministry of Shipping and Island Policy issuing a Circular on 7 June, calling on shipping companies to submit a form with the details of seafarers engaged in international travel, who wish to be vaccinated against COVID-19.

Milestone 200 Anniversary of Greek Independence

Beyond the challenges posed by the pandemic and resultant financial impact, 2021 is a landmark year for Greece as a nation. This year marks the bicentennial celebration since the start of the Greek revolution for independence from the Ottoman empire.

On 25 March 2021, Greece celebrated this historic event which led to the country’s subsequent independence, with a ceremony attended by Prince Charles, and Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin. French President Emmanuel Macron was unable to attend, sending a message in support of Greece and its history. US President Joe Biden also sent a message of support, noting that the relationship between Greece and the US would be closer than ever.

The contribution of foreign sympathisers from countries including Britain, France and Russia, aided the struggle for freedom for Greece, which gained its independence after numerous attempts and almost 400 years under Ottoman rule.

French and US warplanes overflew Athens during the parade in celebration of this historic event.

Maritime Affair

At the outset of 2021, the Shipping and Island Policy Ministry of Greece was reformed with the appointment of a Deputy Minister to join incumbent Minister, Ioannis Plakiotakis.

New Deputy Minister Kostas Katsafados, an MP for Piraeus district, was introduced in an effort better to handle the growing workload and new multiple challenges.

At the same time, the Greek government begun promoting a package of new measures aimed at boosting the attractiveness of the Greek flag as well as seeking to strengthen the competitiveness of the Greek seafarer.

The new measures, at the core of which is the removal of disincentives and the streamlining of procedures related to the selection of the Greek flag, will be incorporated into the existing stable and constitutionally enshrined institutional framework for the registration of oceangoing ships. The new measures will provide greater flexibility in crew employment conditions, reflect international best practices in the foreign crew tax regimes and promote maritime training.

It is also important to note that, as of 1 July 2021, after many years of not been qualified for the program, the Greek flag administration will be included in the eligible list of flags of the USCG QUALSHIP 21. This is an important achievement of the Maritime Safety Division of the Ministry of Shipping and Island Policy of Greece.

Finally, changes in the leadership of the Hellenic Coast Guard took place later in the year. March 2021 saw the appointment of Vice Admiral HCG Nikolaos A. Isakoglou to the position of First Deputy Commandant of the Hellenic Coast Guard. Furthermore, Vice Admiral HCG Georgios Alexandrakis was appointed Second Deputy Commandant of the Hellenic Coast Guard.

Ongoing Tensions in the Aegean and Migrant Issues

Regular Turkish violations of Greek airspace and the Law of Sea have led to tensions in the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean. A number of illegal energy exploration activities by Turkey in the Eastern Mediterranean begun in August 2020, and continued in September and October. The deployment of research vessels by Turkey in Greek territorial waters, escorted by warships, led to increasing tensions.

An incident was also reported near Imia islet, involving the collision of a Hellenic Coast Guard vessel with a Turkish Coast Guard vessel in January this year, while, in the south-eastern Mediterranean, an additional incident, involving the collision of a Greek and a Turkish frigate, had taken place in August last year.

Turkey has faced the threat of sanctions by the EU if it failed to stop its illegal energy exploration activities. Nevertheless, the country has repeatedly ignored calls from Greece as well as the EU to desist, and has persisted in its increasingly aggressive stance.

Exploratory contacts between Greece and Turkey, with a view to resolving the dispute peacefully, took place in March. However, further provocations by senior Turkish officials against Greece, the EU and the United States have not helped to build trust and cooperation.

April saw another serious incident, which violated international regulations, involving vessels of the Turkish Coast Guard and the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, Frontex.

The incidents reportedly occurred off Chios Island, when Turkish Coast Guard vessels violated Greek territorial waters and engaged in dangerous manoeuvres very close to Finnish and Swedish boats patrolling in the eastern Aegean under the umbrella of Frontex’s Poseidon operations, which supports Greece with border surveillance.

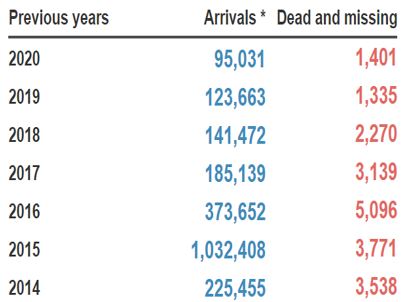

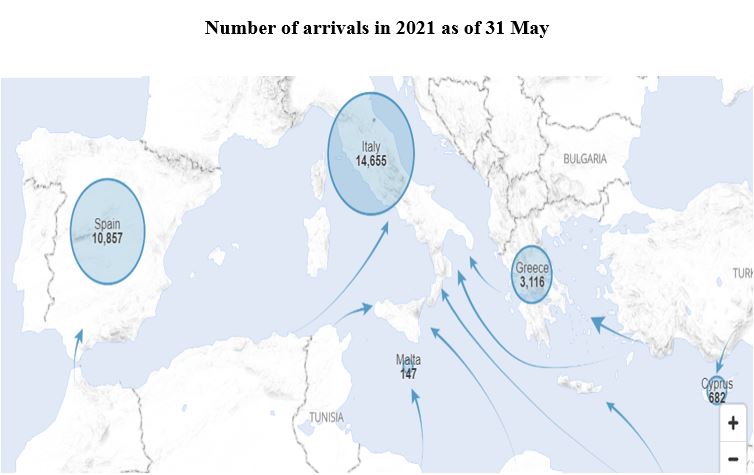

At the same time, the ongoing migrant crisis remains a topical issue affecting Greece, despite the recent decline in the flows of migrants.

As of 11 April 2021, the flows of refugees and migrants to the Greek islands decreased by 89%, compared with the same period in 2020. In all of the accommodation facilities there were 56,000 people as of April, while a year ago this figure stood at 92,000. The decrease led to the closure of at least 70 structures on the mainland this year. Some islands, including Samos, had reported no arrivals since the start of the year, while Chios and Kos saw 99 people arrive as of 14 April 2021. The vast majority of arrivals were recorded in Lesbos.

However, new structures are being built, with the EU announcing funding for five new camps on the Aegean islands of Lesbos, Samos, Chios, Kos and Leros. Over recent months, local people in Lesbos have been demonstrating against the planned camp, calling for decongestion.

At first, the new arrivals were allowed immediately to travel on. However, since 2016 when the agreement between EU and Turkey was struck, migrants and refugees have not been allowed to leave the islands until their status has been decided. Close to 15,000 people still remain on the islands, with the majority of them from Afghanistan (49%), Syria (16%) and Somalia (8%).

(Sources: Hellenic Coast Guard, Bank of Greece, National Public Health Organization (EOΔY), European Parliament, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Seatrade-Maritime, Kathimerini, Skai, in.gr, Greek Reporter, BBC, Reuters, Euronews, Deutsche Welle)

Developments in the UK

Economic Outlook

The pandemic has impacted the economy in many ways. From lockdown restrictions shutting down many businesses to limits on mobility, voluntary and enforced, the economic impact has been severe.

The magnitude of the recession caused by the pandemic is unprecedented in modern times. UK GDP declined by 9.8% in 2020, the largest decline among the G7 countries, and the steepest drop since consistent records began in the UK in 1948.

While output partially recovered in the second half of last year, the last lockdown and temporary disruption to EU-UK trade at the turn of the year negatively impacted output in the first quarter of this year.

According to the UK Office for National Statistics (ONS), UK GDP is estimated to have decreased by 1.5% in Q1 2021. This is 8.7% lower than its pre-pandemic level. However, the economy appears to have adapted well to lockdowns, noting a much smaller decline in economic activity in Q1 2021, compared to the same quarter a year ago, when the initial economic impacts of the pandemic began to show, and the UK economy fell by 6.1%.

Looking ahead, GDP is expected to grow by 4% in 2021, and to regain its pre-pandemic level in the second quarter of 2022. Unemployment is estimated to increase by a further 500,000 to a peak of 6.5% at the end of 2021. The pandemic is also expected to lower the supply capacity of the economy in the medium term by around 3 %, relative to pre-virus expectations.

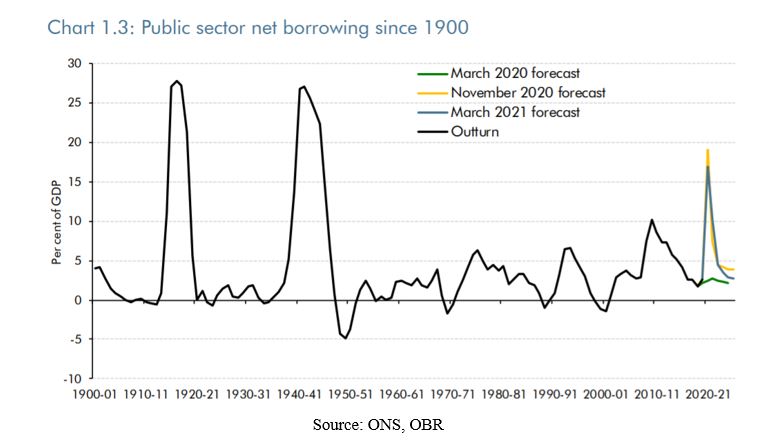

The pandemic has pushed government borrowing up to a post-war high and debt to its highest level in sixty years. In 2020-21, public sector net borrowing is forecast to reach 16.9% of GDP (£355 billion), its highest level since 1944-45, and public sector net debt to rise to 100.2 % of GDP, its highest level since 1960-61. Most of the £298 billion increase in borrowing this year is due to an unprecedented peacetime expansion in government spending, with the full-year cost of the Government’s virus-related support to public services, households, and businesses reaching £250 billion this financial year, £344 billion in total. This support has prevented an even more dramatic fall in output and diminished the potential longer-term adverse effects on the supply capacity of the economy.

Source: ONS, OBR

The March Budget, announced by the Chancellor, involves additional spending to protect the economy in the short-term. This will raise budget and public debt further. A subsequent rise in corporate tax rate as well as the freezing of income tax thresholds was also announced.

Specifically, the Chancellor has extended the virus-related rescue support to households, businesses and public services by a further £44.3 billion. In addition, he has boosted the recovery, most notably through a temporary tax break costing more than £12 billion a year that encourages businesses to bring forward investment spending from the future into this year and next. Finally, as the economy normalises, he has taken a further step to repair the damage to the public finances in the final three years of the forecast by raising the headline corporation tax rate, freezing personal tax allowances and thresholds, and taking around £4 billion a year more off annual departmental spending plans, raising a total of £31.8 billion in 2025-26.

The tax rises and spending cuts announced are sufficient to eliminate all but a £0.9 billion current budget deficit in 2025-26, while they are just enough to see underlying public sector net debt as a share of GDP fall by a similarly small margin of £0.7 billion in 2024-25, and £4.1 billion in 2025-26.

COVID-19

The COVID-19 virus has hit the UK particularly hard, continuing to resurge despite efforts to control its progress.

Following the first wave of the pandemic and strict lockdown measures introduced, the measures relaxed over the summer, with the economy opening up. This was followed by a further short-lived lockdown in November, with restrictions easing, briefly, in December. However, as a new variant of the virus drove up COVID-19 infection rates in December, lockdowns were again introduced across the UK by early January 2021, to reduce the spread of the virus. In late February, the Government announced a roadmap for the gradual lifting of public health restrictions, with the planned opening progressively materialising from April onwards as infection rates remained low.

After the resurgence of infections over the winter, around 1 in 5 people had contracted the virus, 1 in 150 had been hospitalised, and 1 in 550 had died, one of the highest mortality rates in the world. The grim milestone of 100,000 deaths attributable to COVID-19 has been long passed and the total continues to grow, with each death a terrible loss. The total number of UK deaths, with COVID-19 on the death certificate, stood at 152,183 as of 6 June 2021.

The pandemic has, however, also spurred a global scientific effort to develop new and effective vaccines at unprecedented speed, with the UK in the vanguard of their discovery and rollout.

The mass vaccination programme in the UK began in December 2020, and is well underway bringing hope of a gradual return to normal interaction and a sustained economic recovery.

Currently, more than 40 million UK residents have received their first dose of the vaccine, the fourth highest vaccination rate worldwide. The total number of people who have received both doses as of 5 June 2021, stood at 27,661,353, representing 52.5% of the country’s adult population. The UK government aims to have offered a first dose to all adults by 31 July.

Although the rollout of vaccines means that risks posed by COVID-19 will gradually reduce, the virus, in different forms, will be with us for years to come. Continuing to tackle this, and reduce its impact on people facing health inequalities, will be a key task for public health long into the future.

New UK Maritime Minister

On 8 September 2020, Robert Courts was appointed as Parliamentary Under Secretary of State at the Department for Transport responsible for maritime, aviation affairs, and security and civil contingencies.

This is the first ministerial role for former barrister Robert Courts, who has served as the MP for Witney in Oxfordshire since 2016, when he held the seat in a by-election following the resignation of former prime minister David Cameron. In August 2019 he was appointed Parliamentary Private Secretary to the Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. Courts is a member of the Marine Conservation Society and has a great interest in the maritime environment.

In a cabinet reshuffle, Kelly Tolhurst moved to the Local Government Department, after only seven months of overseeing maritime affairs. During her short tenure as shipping minister, Tolhurst led an international virtual summit in July 2020, on the crew crisis during the pandemic. The 13 participating countries, including Norway, Denmark, the Philippines and the UK, had agreed on new international measures to open borders for seafarers and increase the number of commercial flights to expedite repatriation efforts.

It should be noted that while many countries around the world closed their borders to seafarers at some point during the pandemic, the UK remained accessible for crew changes and transits, demonstrating its continued support of the maritime industry.

Brexit

While the UK had voted to leave the EU in 2016, and officially left on 31 January 2020, the agreed transition period, during which previous conditions remained unchanged, ended on 31 December 2020.

The deadline for reaching an agreement on a trade deal between the two parties was set for the end of 2020. On 24 December 2020, days before the deadline, the UK and EU finally reached an agreement, which sets out the rules on the new partnership between the two parties.

The Trade and Co-operation Agreement (TCA) has been operating provisionally since January, bringing stability to the new relationship between the two parties. The post-Brexit EU-UK trade deal was a key move to ensure that tariff and quota-free trade continues. However, as of 1 January, the free movement of people and services ended, bringing about significant differences to how people live, work and travel between the EU and UK. Businesses also need to become familiar with the new procedures and paperwork required in order to avoid disruptions.

The full UK-EU trade agreement is more than 1,200 pages long but its key points are as follows:

- The agreement retains the position of no tariffs or quotas on goods traded between the UK and the EU, subject to meeting appropriate qualifying conditions, such as those on ‘rules of origin’. Some new checks will be introduced at borders, such as safety checks and customs declarations.

- There will be no role in the UK for the European Court of Justice. Disputes that cannot be resolved between the UK and the EU will be referred to an independent tribunal instead.

- The agreement introduces significant barriers to trade in services. While the deal follows the broad ambition set in the EU-Canada FTA mutually to recognise professional qualifications, no qualifications have yet been recognised under this framework. The mobility of service workers is now subject to significant restrictions. In terms of market access for services, the TPO notes that while the deal is similar to EU agreements with Canada and Japan, in practice there will be a variety of rules in supplying services to each member state, meaning that many firms will need to establish a new commercial presence within the EU.

- The deal makes little reference to the “cross-border provision” of financial services and many of the EU’s unilateral equivalence decisions for the UK have been postponed. The UK and EU are aiming to agree, over the coming months, a ‘memorandum of understanding’ on the future framework for financial services regulation.

(Sources: UK Government, House of Commons Library, Office for Budget Responsibility, Office for National Statistics, Bank of England, UK Local Government Association, UK National Health Service, Public Health England, TradeWinds, BBC, Nautilus International, KPMG)

COVID-19 Pandemic – Impact on International Shipping

More than a year since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, millions of lives have been lost, while the financial impact is weighing heavily on the world’s economy. Globally, as of 4 June 2021, there have been 171,708,011 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 3,697,151 deaths, according to WHO. Lockdowns, reduced demand, increased unemployment and debt, led to a 4.2% reduction in global GDP in 2020, and a significant drop in industrial production, according to IHS Markit.

These are exceptionally challenging times for the society and naturally, for the maritime industry. With international transport at the forefront of trade, dependent on travel and human interaction, the shipping industry has been impacted both directly and indirectly from the outbreak of COVID-19.

The cruise sector and in general the transport of passengers are the sectors most heavily impacted by the COVID-19. Other sectors were also impacted, but in general the trade didn’t stop. Commercial ship operations, ports and other maritime transport sectors continued to operate, despite facing various difficulties, ensuring the movement of goods and proving the strategic importance of the maritime sector for our livelihood.

Seafarers in international trade are constantly facing the risk of being infected by COVID-19, and measures implemented by countries to prevent the further spread of the virus have brought serious operational consequences for vessels and crews. Travel restrictions due to the pandemic have made it exceptionally difficult to effect crew-change on ships.

Ports around the world have either refused or placed significant hurdles in the way of off-signing seafarers, all of which have posed a risk to the health of the crew as well as having increased the costs of handling such matters. The effects of COVID-19 have not been limited to cases of the virus itself. A wide array of crew-related matters have suffered from the delay and increased regulation. Routine off-signing has had to be planned well in advance, where it is possible at all, and emergency disembarkation has been refused on numerous occasions, often despite an urgent medical need.

Supply chain disruptions, shortage of workforce and implementation of social distancing measures in ports and shipyards have been causing delays. Shipping companies have had to adapt to the new challenges following inadequate or unclear terms in charterparties as to who is to bear the brunt of time lost due to quarantine or crew-related delays. BIMCO has reacted by publishing a bespoke COVID-19 clause in late June 2020.

Throughout the pandemic, shipping has demonstrated its reliability and resilience as one of the most economic and effective modes of transport. The industry has sought to provide workable solutions to local governments to help effect crew changes safely and efficiently, as well as maintaining the flow of goods across the globe during these difficult times.

However, the life and work of seafarers is still being affected dramatically by the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the IMO, in the last quarter of 2020, the estimated number of seafarers globally waiting to either be relieved or join their ships stood at 400,000. In May 2021, thanks to the collaborative efforts of IMO and its Member States, the shipping industry, social partners and UN agencies, the number is currently estimated to be about 200,000.

Nevertheless, this figure is still unacceptably high and the humanitarian crisis at sea is by no means over. As of May 2021, only 58 of the 174 IMO Member States had designated seafarers as “key workers”, despite repeated calls by the Organization to its Member States to give “key worker” status to seafarers and marine personnel.

Seafarers still face enormous challenges concerning repatriation, travelling to join their ships, proper access to medical care and shore leave. Despite these challenges, the seafarers on board ships have continued working, providing an essential service for the global population.

The prioritisation of the COVID-19 vaccination for seafarers is a new challenge for the international community. The GSCC, the shipping industry and the IMO have led calls for governments to put seafarers at the head of the vaccine queue and to designate seafarers as keyworkers.

A “Roadmap for Vaccination of International Seafarers”, prepared and launched by ICS and supported by a broad cross section of global industry associations representing the maritime transportation sector, was issued in May. The roadmap sets out procedures for a programme that can be implemented by all stakeholders concerned, including shipping companies, maritime administrations and national health authorities, to facilitate safe ship crew vaccination during the pandemic.

The IMO has been actively working with its Member States and the maritime industry to find solutions to enable and accelerate the vaccination of seafarers in order to protect them as soon as possible, and to facilitate their safe movement across borders. The Organization has been supporting the COVAX initiative of WHO, towards access to vaccines in countries with limited resources. As some key maritime labour supply countries currently rely on this initiative, a fair global distribution will also enable these seafarers to continue with their maritime careers.

In the global fight against the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccination of populations is a key step. While the roll-out of COVID-19 vaccines has brought hope that the end of the pandemic is in sight, the production and distribution of vaccines are complex processes that will take time. The roll-out of vaccination programs varies enormously from country to country and it may take years before most of the global population has been vaccinated. As of 2 June 2021, a total of 1,638,006,899 vaccine doses have been administered, according to WHO.

To conclude, many seafarers have endured intense hardship while working to keep trade flowing. To address the ongoing humanitarian crisis at sea, it is essential that national governments designate seafarers and marine personnel as “key workers” and offer them priority to receive COVID-19 vaccination. It is also crucial to demonstrate solidarity and continue working together to overcome this challenging situation for global shipping sooner rather than later. The health of the world’s seafarers and the safety of their workplaces must remain one of our main priorities.

(Sources: World Health Organization, International Maritime Organization, International Chamber of Shipping, European Maritime Safety Agency, GARD P&I Club, West of England P&I Club, Standard P&I Club, IHS Markit)

IMO Decarbonisation Roadmap

Background

Decarbonisation and sustainability are key considerations in the future of the shipping sector. The international shipping industry, responsible for the carriage of around 90% of world trade, accounts for a relatively small share of global CO₂ emissions, estimated between 2% and 3%. The IMO has mapped out an ambitious pathway towards a carbon neutral industry. The ultimate goal is an important one for the planet, but there are likely to be disruptions and challenges along the way that make it important for all stakeholders to plan and prepare in order for it to succeed.

The IMO initial Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Strategy was approved in 2018, envisaging a reduction in carbon intensity of international shipping.

The first goal is an average reduction across international shipping of at least 40% in CO₂ levels by 2030, as compared to 2008 levels.

Subsequently, by 2050, it is intended that CO₂ levels will be further reduced by 70%, compared to 2008.

Overall, the Strategy aims to reduce the total annual GHG emissions from international shipping by at least 50% by 2050, compared to 2008, whilst pursuing efforts towards phasing them out, in line with the Paris Agreement.

In November 2020, MEPC 75 adopted amendments to MARPOL Annex VI on early application of Phase 3 of the Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI), applying for new vessels. This meant that application of the EEDI Phase 3 was brought forward from 2025 to April 2022 for container ships, large gas carriers, general cargo vessels, LNG carriers and cruise ships with non-conventional propulsion.

In addition, a package of new short-term measures was approved by MEPC 75, pending adoption at MEPC 76, and expected to enter into force by January 2023, with the aim of achieving the 2030 CO₂ reduction goal.

The measures involve technical and operational requirements, introducing the following:

- The Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index (EEXI) for existing vessels.

- A Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII) regulating and annually monitoring the operational carbon intensity performance, setting a mandatory reduction of operational emissions.

- The enhanced use and auditing of the Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan (SEEMP).

Furthermore, MEPC 75 decided to give further consideration to a proposal from the industry collectively to provide USD 5 billion to accelerate R&D to support its decarbonisation. The proposed programme, to be conducted by a new International Maritime Research and Development Board, would be supervised by the IMO and financed by the industry, aiming to be operational by 2023.

MEPC 75 also officially approved the 4th IMO GHG Study 2020, published in August 2020. This was commended by many delegations for its scientific quality. The study had indicated a significant decrease of carbon intensity in the period under review, reflecting that the previously agreed IMO measures were starting to have a positive effect. Specifically, the study found that despite a 40% growth in maritime trade between 2008-2018, carbon intensity of international shipping improved by roughly 30%, and total GHG emissions from shipping dropped by 7% during the same period.

More recently, the IMO Intersessional Working Group on Reduction of GHG Emissions from Ships, which met in late May, agreed on a set of guidelines accompanying the new requirements, with a view to adoption at MEPC 76. The guidelines have a focus on the method of calculation of the attained EEXI; on survey and certification of the EEXI; and on the CII calculation methods and rating of ships, among others.

A Correspondence Group on Carbon Intensity Reduction has also been established. Amongst other things, this will develop draft guidelines on correction factors for certain ship types, operational profiles and/or voyages for the CII calculations, finalise the Guidelines for the development of a SEEMP, its audit and verification processes.

The outcome of MEPC 76, which will conclude on 17 June, is key for the way forward with the next steps, while it is hoped to bring much needed clarity on the calculation and compliance with the new measures.

In future, IMO’s Initial GHG Strategy is to be revised by 2023. The effectiveness of the implementation of the CII and EEXI requirements will also be reviewed, by 1 January 2026 at the latest, and, if necessary, further amendments will be developed.

New Requirements

In order to enable shipping to meet its emissions reduction targets, the IMO has set various energy efficiency standards, which will need to be met by new and existing ships in the coming years.

Newbuilds – EEDI

In 2013, the IMO introduced the Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI), which applies to newbuilds and is measured in terms of CO₂ emitted per capacity. The EEDI is being implemented in phases:

- Under phase 1, ships built in 2015 onwards were required to have a 10% reduction in CO₂ levels as compared to those built in 2013.

- Phase 2, currently in process, requires ships built in 2020 and onwards to have a 20% CO₂ reduction.

- In phase 3, from 2025 onwards, and from 2022 for some ship types, a 30% CO₂ reduction will be required.

It should be noted that the IMO is considering whether Phase 4 will be expanded to cover all GHG emitted from ships.

Existing Ships – EEXI

Recognising that the EEDI scheme for newbuilds was not enough on its own to meet the CO₂ reduction targets, the IMO determined that existing ships also need to be made more efficient. The EEXI will be applicable for all vessels above 400 GT, falling under MARPOL Annex VI.

Like the EEDI, the EEXI is a technical or ‘design’ efficiency index which requires a vessel to achieve a required level of technical efficiency i.e., the required EEXI.

The required EEXI is the vessel’s required maximum grams of CO₂ emitted by the vessel per capacity (deadweight) tonne mile under reference conditions, given its type and capacity.

All existing ships will be required to meet this efficiency standard by 2023 or earlier.

A vessel will be ascribed an Attained EEXI, calculated by reference to technical guidelines, which are being finalised by the IMO. As the calculation process should be familiar and consistent with EEDI, it could be relatively quick to implement.

In its simplest form, the attained EEXI is the vessel’s grams of CO₂ emitted per capacity tonne mile under the ship specific reference conditions. This is a function of the installed engine power (kW), the specific fuel consumption of the main and auxiliary engines and a carbon factor representing the conversion of fuel to CO₂, vessel capacity and vessel reference speed. However, there are many different correction factors and nuances which apply, depending on the ship type and capacity.

A draft example of the possible applicable reduction factors depending on the ship type and range, prepared by Lloyd’s Register, is provided below.

Source: Lloyd’s Register

The information and specific formulas required to calculate the Attained EEXI will be contained in the vessel’s EEXI Technical File.

The EEXI Technical File will need to be approved by the vessel’s Flag State or Class at the first annual/intermediate/renewal International Air Pollution Prevention Certification (IAPPC) survey taking place after entry into force.

For ships which comply, a new International Energy Efficiency Certificate (IEEC), which will state the required EEXI and compliant attained EEXI, will be issued.

If the Attained EEXI is less efficient than the Required EEXI, the vessel will be required to take measures to meet the Required EEXI levels. As compliance is determined by the vessel’s design and arrangements, an attained EEXI can only be changed through alterations to the vessel’s design or machinery.

The EEXI will necessitate technical upgrades to many ships, such as hull, rudder and propeller improvements etc. The Regulations do not, however, prescribe which improvement method should be deployed.

EEXI Compliance Steps

The EEXI Technical File will be used as a basis for verification of compliance with EEXI. In addition, ships using Overridable Power Limitation (OPL) to comply with EEXI should develop an Onboard Management Manual (OMM) based on guidance which will be approved by the IMO in MEPC 76. This should be done as soon as possible after June 2021.

According to LR, the route to EEXI compliance is as follows:

- For pre-EEDI ships, calculate the attained EEXI and determine if it is equal to or lower than the required EEXI. For EEDI-certified ships, determine whether the attained EEDI is equal to or lower than the required EEXI.

- For EEDI-certified ships which have an attained EEDI which is less than or equal to the required EEXI, refer to number 6 below.

- For ships where the calculated (attained) EEXI / EEDI is greater than the required EEXI, take action to improve the attained EEXI. In addition to retrofitting of Energy Efficiency Technologies (EETs), or switching to a lower carbon fuel (other than a drop-in alternative fuel), EEXI allows the use of OPL to limit operational engine loads and fuel consumption. OPL may be either Engine Power Limitation (EPL) or Shaft Power Limitation (SHaPoLi).

- Re-evaluate the attained EEXI following any action taken to improve the attained EEXI.

- If the attained EEXI is less than or equal to the required, prepare the EEXI Technical file, which includes the data used for calculation of the attained EEXI.

- Apply to the Administration or a Recognised Organization to issue the new IEEC. Where OPL is used to comply, issue of the IEEC will be subject to verification of the attained EEXI based on the EEXI Technical File and the OPL arrangements and OMM.

Vessels which have not demonstrated compliance will be unable to trade internationally.

Given the work required to ensure compliance, and large number of vessels effected, the time available for shipowners to demonstrate compliance is short.

Calculating the EEXI, developing the EEXI Technical File and OMM, if applicable, is relatively straightforward, however, a significant proportion of vessels will be required to take action to improve the attained EEXI. Early action to understand the impact of EEXI and the cost-effective compliance options available is essential, according to LR.

New and Existing ships – CII

The CII focuses on operational aspects and seeks to ensure improvement of the ship’s operational carbon intensity. CII will regulate the CO₂ emissions per unit of ‘transport work’ or the operating mileage in a given year, and will apply to vessels above 5,000 GT.

Vessels will be given an annual carbon intensity rating (CII Rating). A vessel’s CII Rating for a given year will be generated by monitoring/documenting the actual operational carbon intensity achieved by the vessel (Attained Annual Operational CII), and then comparing this against the required operational carbon intensity that the vessel must achieve under the framework (Required Annual Operational CII). The Attained Annual Operational CII of any given vessel should improve annually.

There are five CII Rating categories representing different performance levels, as follows: A (major superior); B (minor superior); C (moderate); D (minor inferior); and E (inferior). The minimum CII Rating required for compliance is C. Flag States, port authorities and other stakeholders have received encouragement from the IMO to provide incentives to those vessels achieving a CII Rating of A or B.

If a ship’s rating falls below C it will not be allowed to trade until corrective action is carried out. A vessel rated D for three consecutive years, or rated E at any point, must develop a plan of corrective actions to achieve the Required Annual Operational CII for its age, type and size. The plan must be set out in the Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan (SEEMP) within one month after reporting the vessel’s Attained Annual Operational CII, and will be verified by the Flag State.

The thresholds between the CII Rating categories will become increasingly stringent towards 2030. With CII targets becoming increasingly strict year on year, vessels might need regular improvements in order to enhance their CII grading and continue trading. As we are moving closer to 2023, companies will be required to ensure that they have programmes in place to upgrade existing vessels to a suitable efficiency level. However, the regulations are not especially prescriptive and it is largely up to owners how they seek to achieve this.

The Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan (SEEMP), required for vessels under the CII framework, should include the following:

- the methodology used to monitor and calculate the relevant vessel’s Attained Annual Operational CII;

- a Required Annual Operational CII for the next three years;

- an implementation plan describing how the Required Annual Operational CII target will be achieved over the next three years (to achieve a continuous improvement); and

- a procedure for self-evaluation and improvement.

CII Compliance Steps

Ships will need to consider operational measures such as slow steaming and “just-in-time arrival” to address CII compliance in the short term, and for the longer term alternative fuels will need to be considered.

The formal metric to calculate a vessel’s Attained Annual Operational CII is yet to be confirmed, with technical guidelines awaited from the IMO. At present, the two options under consideration are:

- the Energy Efficiency Operational Indicator (EEOI), a metric previously developed by the IMO, which works by dividing a vessel’s annual carbon emissions by its annual cargo tonne miles; or

- the Annual Efficiency Ratio (AER), which works by dividing a vessel’s annual carbon emissions by its annual DWT miles.

Currently, AER data is being collected and is readily available by virtue of the IMO’s Data Collection System (DCS). Whilst EEOI data would require further monitoring and reporting, it should be noted that such data is being used by signatories to the Sea Cargo Charter, a framework available to all bulk charterers in order to attempt to set standards for reporting emissions.

At the moment, there is indication that AER could be the defining factor for the efficiency of a ship going forward. However, there is scepticism about this metric as it encourages increasing distances travelled at lower rates of fuel consumption. Concerns regarding the penalisation of the most high-payload and high-productivity ships have also been expressed.

Irrespective of which CII metric (AER or EEOI) will apply, broadly speaking, the vessel’s Attained Annual Operational CII can be improved by:

- operating at a reduced speed and/or slow steaming;

- diverting from the shortest or quickest route on a voyage/increasing distance sailed (including ballast voyages for AER);

- reducing cargo volume intake (for AER); and/or

- installing energy efficient technology.

The Road Ahead – An Unknown Future

Overall, the IMO Regulations come at a time when a number of regional measures to reduce GHG emissions from maritime transport are also being discussed. For example, the EU has confirmed its intention to include shipping within its Emissions Trading System, and China has likewise indicated that shipping may soon be covered under its national carbon trading scheme. The US has also indicated that it may be leaning towards a carbon tariff system of some nature.

The IMO’s approach, however, more directly monitors and incentivises the improvement of a vessel’s energy efficiency and reduction of carbon intensity by focusing on both its technical design and operations. In this regard, the Regulations go beyond simply imposing a tax on GHG emissions.

Regulatory change will be the driving force in innovations within design and manufacturing, which it is hoped will enable the advancements in technology needed to fulfil the industry’s expectations. However, the use of new technologies, operational procedures and fuels will also carry inevitable challenges, cost and potential for disputes.

There is a plethora of technological and design solutions in the market, as shown in the table below, prepared by ABS. However, with continued uncertainty about the specifics of the upcoming IMO requirements, many stakeholders do not yet know how to prepare for the new regulations. At present, efforts are being made throughout the shipping industry to prepare fleets for the new IMO CO₂ regulation. With no clarity yet on practical, tested and effective solutions, fleet renewal plans and crucial investments decisions are impeded.

Source: ABS

(Sources: International Maritime Organization, Lloyd’s Register, ABS, DNV, UK Defence Club, International Chamber of Shipping, BIMCO, International Union of Marine Insurance, Holman Fenwick Willan LLP, International Institute for Sustainable Development, Shipping watch)

EU Environmental Proposal & Other National Schemes

Managing the GHG emissions of the maritime sector is currently under the EU spotlight as well as for a number of national governments around the world.

In December 2019, the European Commission announced its new Green Deal, which proposed to extend European emissions trading to the maritime sector. Subsequently, in September 2020, the European Parliament adopted amendments in order to:

- Include shipping in the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) from 2022;

- Reduce shipping’s annual CO₂ emissions per transport work by at least 40% on a linear basis by 2030, with penalties for non-compliance.

- Establish a Maritime Transport Decarbonisation Fund, entitled “Ocean Fund”, financed by ETS revenues, to support investment in the decarbonisation of maritime transport for the period 2022-2030.

However, in light of comparable IMO measures, the Commission will be required to review the regulation in the future.

Further details regarding the new rules in the Commission’s package of energy and climate laws are expected to be agreed during its upcoming meeting on 14 July.

Although details are still under discussion, it is anticipated that from 2022, the ETS scheme will affect the majority of ships over 5,000 GT performing voyages that start or finish in the EU. It is not yet clear which party will be responsible for ensuring compliance with the scheme, although the draft proposals identify the party responsible for paying for the fuel as being the party obliged to obtain the applicable allowance.

In addition, the European Commission plans to propose the “Fit for 55” legislative package in July fundamentally to put the EU on track to deliver on its 2030 climate target of 55% reduction of GHG emissions.

With the exception of the Monitoring Reporting and Verification (MRV) scheme, the “Fit for 55” package contains all the expected measures including, but not limited to, a revision of the EU Emission Trading System and the Energy Tax Directive, a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, and an amendment of the alternative fuels infrastructure Directive. Therefore, the discussion on the amendments of the MRV Regulation and its partial alignment with the IMO mandatory fuel oil data collection systems (DCS) at the moment appears to be on hold.

The UK, from its side, has introduced a reporting scheme relevant for shipping companies after Brexit. As of 1 January 2021, the UK MRV became the third CO₂ reporting scheme, alongside the EU MRV and IMO DCS.

The UK MRV is applicable to vessels >5000 GT calling at UK ports. By 2022, operators and managers responsible for vessels subject to the UK MRV scheme shall submit their first annual emissions report for 2021. It should be noted that the EU MRV will remain valid for the UK MRV, i.e. no separate UK MRV monitoring plan will be required. By carrying the EU MRV monitoring plan, the vessel will comply with both the UK MRV and EU MRV regulations.

Furthermore, the UK has also implemented its own Emissions Trading Scheme (UK ETS). The UK ETS replaced the UK’s participation in the EU ETS on 1 January 2021. The UK ETS largely mirrors its EU counterpart but is subject to the UK’s more ambitious target of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. Nevertheless, at the moment, it remains unclear whether the UK ETS will apply to the maritime sector.

Other national emissions trading schemes are under consideration, with shipping likely to be targeted. The US has introduced the Ocean-Based Climate Solutions Act in October 2020. This addresses a number of topics, and will encourage discussion on the country’s future action including shipping and GHG. The Act includes a proposal, which is similar to EU’s approach, regarding the introduction of carbon pricing on shipping.

China also recently introduced its national emissions trading scheme. China’s ETS entered into force in February 2021, with a focus, during its initial phase, on regulating entities from the power sector. The recent move does not appear to cover the shipping industry at the moment. Trading is expected to commence this July, covering CO₂ emissions during 2019-2020. However, experts have warned that the introduction of the China ETS will do little to curb China’s emissions in the short-term, and does not incentivise a reduction in coal fuelled power generation.

Overall, the proposed extension of EU ETS to the maritime sector as well as other suggested national schemes could lead to multiple regimes where compliance is costly, time-consuming and, more importantly, does not yield the desired result.

In addition, a number of international shipping organisations and countries, including Japan, South Korea, Russia and Brazil, have urged the Commission to reverse course, warning that the inclusion of shipping to EU’s carbon market could stoke trade tensions, and cause extra emissions by prompting ships to take longer routes to avoid stops in Europe.

It is possible that the application of EU ETS to international shipping could have adverse repercussions on both environmental integrity and sustainability of global maritime transport and trade. Therefore, the extension of the EU ETS to international shipping is not viewed as the right way forward by a large number of international shipping organisations.

Shipping bodies ICS, BIMCO, CLIA, World Shipping Council, along with other industry groups have also warned against unilateral carbon pricing initiatives such as the EU’s ETS, as they create a market distorting solution to a global problem.

Further concerns have been expressed by the industry regarding shipping’s inclusion to a carbon market, arguing that it is too early for such a move due to the current lack of commercially viable technologies to cut emissions.

ECSA also stated that the EU ETS proposal is putting unrealistic pressure on IMO as regional measures will gravely hurt a global sector and do very little for the climate. The association supports that this would unduly complicate the achievement of an effective and timely global agreement in IMO.

The EU has ignored calls, from the IMO, INTERCARGO and the industry as a whole for collaboration and adapted solutions to achieve the much-needed reduction in GHG.

Overall, global challenges and problems require global handling and solutions. There has already been significant progress made by the IMO, with an ambitious strategy and concrete targets for reducing CO₂ emissions in place, while the Organization is actively considering a number of alternatives such as Market-Based Measures, a global fuel levy, and the establishment of a board, funded by the industry to accelerate the R&D effort required to decarbonise shipping.

The inclusion of shipping in the EU ETS could potentially have serious implications for progress at IMO with respect to achieving further reductions of the total GHG emissions by the international shipping sector as a whole. Undoubtedly, a global strategy led by the IMO would be the most effective way to reduce emissions from international shipping in the most comprehensive way.

(Sources: European Commission, UK Defence Club, International Chamber of Shipping, European Community Shipowners’ Associations, INTERCARGO, Holman Fenwick Willan LLP, Watson Farley & Williams LLP, Hill Dickinson LLP, DNV – Stamatis Fradelos, Lloyd’s Register, Lloyd’s List, Wall Street Journal, Maritime Professional, Ship and Bunker, Shipping Watch)

Cyber Security

The pandemic had a seismic effect on all our lives, exerted a significant impact on trading and, out of urgent necessity, transformed working practices the world over. The availability of high-speed, high-quality connectivity has been an invaluable asset, enabling organisations to maintain their business continuity.

The corresponding downside has been an alarming escalation in the incidence of cybercrime, with some high-profile shipping companies having recently borne the brunt of these attacks. The regrettable fact is that the same critical pressure which forced organisations everywhere rapidly to move so many aspects of their operations online conversely represented a golden opportunity for hackers.

To cope with operational issues such as denied physical access, quarantined vessels and travel restrictions, companies are actively opening for remote access, implementing remote digital survey tools towards vessels and encouraging shore staff to work remotely from home. There is also increased use of mobile devices to access operational systems onboard vessels and core business systems in the company.

With more technological transformation, use of cloud, and broader networking capabilities towards vessels, the threat landscape continues to increase. Unprotected devices can lead to the loss of data, privacy breaches, and systems being held at ransom.

Four prominent container operating firms, accounting for almost 60% of the world’s container traffic, fell victim to malware or ransomware attacks within months of each other.

On 30 September 2020, the IMO was also hit by a cyber-attack, with IMO’s website and web-based services remaining unavailable for a couple of days. The Organization stated on Twitter that “the interruption of service was caused by a sophisticated cyber-attack against the Organization’s IT systems that overcame robust security measures in place”. IMO IT technicians shut down key systems to prevent further damage from the attack. The attack came only two days after container line CMA CGM was hit with malware, forcing it to take its e-commerce systems off line and resulting in a suspected data breach.

As cyber threats are on the rise, the entry into force of the IMO Cyber Security Guidelines on 1 January 2021, is timely and will have a beneficial influence upon the take-up of effective maritime cyber risk management programs. The guidelines will provide a consistent benchmark, a framework within which companies can measure their cyber-attack preparedness.

IMO Guidelines

Recognising the urgent need to raise awareness on cyber risk threats to support safe and secure shipping, the IMO, in 2017, issued MSC-FAL.1/Circ.3 “Guidelines on Maritime Cyber Risk Management”.

The IMO, furthermore, adopted Resolution MSC.428(98) “Maritime Cyber Risk Management in Safety Management Systems”, which encourages Administrations to ensure that cyber risks are appropriately addressed in existing Safety Management Systems as defined in the ISM Code, no later than the first annual verification of the company’s Document of Compliance after 1st January 2021.

In practice, shipowners will need to demonstrate a full understanding of mandated cyber security protocols by conducting a comprehensive inventory of all at-risk onboard and offshore systems, including IT and OT equipment.

Vessels will then be subject to a cyber risk analysis and evaluation to assess their vulnerability and the mitigation measures, which have been or need to be applied on board.

Thereafter, shipowners can implement a cyber risk management program best suited to their vessels and equipment, establishing crisis management strategies and incorporating crew training procedures, which clearly demarcate their specific roles and responsibilities.

The IMO Cyber Security Guidelines involve five basic steps, based upon the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) framework:

- Identifying risk;

- Detecting risk;

- Protecting assets;

- Responding to risk;

- Recovering from attacks.

United States Coast Guard (USCG) Guidelines

The USCG has issued information on how they will ensure compliance with IMO Resolution MSC.428(98). In November 2020, the USCG published Work Instruction CVC-WI-027 “Vessel Cyber Risk Management”, which provides guidance to USCG Marine Inspectors and Port State Control Officers for assessing cyber hygiene onboard applicable vessels, as well as compliance options in case deficiencies are noted.

The USCG requires all ships, irrespective of flag, which call at US ports, to ensure that cyber risk management is appropriately addressed in their Safety Management System (SMS) by the company’s first annual verification of the Document of Compliance after 1st January, 2021. Failure to comply with this requirement may result in vessel detention.

The key points of the USCG’s Work Instruction CVC-WI-027(1) are as follows:

- Serious deficiencies will require rectifying and an external audit within 90 days, or risk detention.

- Minor deficiencies will need an internal audit within 90 days, and the deficiencies to be rectified prior to departure.

- Inspections will only cover networked systems directly relevant to vessel safety.

- Where faults have occurred in systems which are critical for vessel safety, the inspector/Port State Control officer is mandated to investigate if the cause of the fault was ‘cyber-related’, and if so whether the right procedures were followed prior to that fault occurring. The systems critical for vessel safety include the ballast control, engine & propulsion control, rudder control, cargo control, navigation (ECDIS/GPS), radar, satellite & 3/4/5G communications, and on-board welfare systems. Stand-alone systems, or other systems ‘which do not affect the safe operation or navigation of the vessel” are not to be inspected or examined.

- If the inspector believes there are clear grounds for an expanded inspection, and clear evidence is gathered of poor implementation of the cyber risk management element of the SMS, further deficiencies may be issued.

When inspecting a vessel, the USCG Port State Control Officer will be looking for a fully-integrated cyber-risk management system within its SMS, with documentary evidence to prove this.

In addition, the Officers have been tasked to look out for evidence of problems including, but not limited to, the following:

- Poor cyber hygiene (such as password and/or logins on open display, generic logins or no logins, no automatic logout after a period of inactivity, heavy reliance on USB drives and no obvious means of virus checking prior to use);

- Evidence of malware on ship computers: popups and/or any ransomware;

- Records or complaints of unusual network activity and/or reliability issues impacting shipboard systems;

- Spoofed/phishing e-mails purporting to come from the Master and/or crew members.

Overall, the USCG guidelines are clear about their requirements, approach and ensuing actions. So far, there have been no cyber security related deficiencies or detentions reported. However, as managing cyber risks is being regarded increasingly crucial for vessel safety, cyber hygiene and the integration of cyber risk management into vessels’ SMS will most likely come under the spotlight in the future.

With regard to assessing compliance, the USCG favours the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) framework, but recognises that the IMO assessment follows the broad direction of this framework, and the organisations are therefore working together. The USCG has also recognised other frameworks such as the International Organization for Standardization/International Electrotechnical Commission (ISO/IEC) and the industry “Guidelines on Cyber Security Onboard Ships”, which are heavily based on the NIST framework.

In late December 2020, Version 4 of these industry cyber risk management guidelines was published, laying the foundation for further improvements and refinement of companies’ cyber security risk assessments. Among the various organisations which have contributed in producing the updated guidelines are BIMCO, ICS, INTERCARGO and INTERTANKO.

The fourth version contains general updates to best practises in the field of cyber risk management and, as a key feature, includes a section with improved guidance on the concept of risk and risk management. The improved risk model takes into consideration the threat as the product of capability, opportunity, and intent, and explains the likelihood of a cyber incident as the product of vulnerability and threat. Thus, the improved risk model offers explanation as to why relatively few safety-related incidents have so far unfolded in the maritime industry, but also clarifies that this should not be misinterpreted and cause shipping companies to become complacent and lower their guard.

With increased connectivity and digitalisation, more vulnerabilities in need of safeguarding will emerge in the future. It is therefore vital that companies are informed and ready to implement the necessary protection within their systems.

A good start has already been made for some companies when it comes to ensuring compliance with the new guidelines, but for many organisations, there is still quite a journey to achieve a fully mature cyber programme on board their vessels.

In addition to the increasing and ever evolving cyber threats, IMO’s Cyber Security Guidelines and the strict approach of the USCG are undoubtedly the driving forces behind the changes within marine cyber security.

The maritime industry is gradually gaining more understanding of the practicalities of cyber security and why it is so important to have safe, secure and robust measures in place in the current environment.

(Sources: International Maritime Organization, US Coast Guard, BIMCO, UK P&I Club, GARD P&I Club, West of England P&I Club, International Institute of Marine Surveying, Seatrade-Maritime, Maritime-Executive, Safety4Sea, Journal of Commerce)

Piracy

Overview

Adding to the COVID-19 hardships already faced by seafarers, 2020 saw a year-on-year increase in global piracy.

In 2020, the International Chamber of Commerce’s International Maritime Bureau (IMB) Piracy Reporting Centre (PRC) recorded 195 incidents of piracy worldwide, in comparison to 162 in 2019, representing an increase of just over 20%.

The rise is attributed to an increase of piracy within the Gulf of Guinea, as well as increased armed robbery activity in the Singapore Straits.

Source: ICC/IMB