By James Brewer

Dieppe was an ideal base for the unflagging painter Walter Sickert. The French resort offered him ever-changing views of his favourite subject-matter: café-concert venues, everyday street scenes, the harbour, and seascapes.

Sickert (1860-1942), who was to become one of Britain’s most influential artists, spent from 1898 to 1905 residing in – and when he went back to London visiting regularly for four decades – the seaside town which over the years has fallen in and out of fashion. Today, the port’s website says that it is France’s “oldest seaside resort as well as the closest to Paris. Dieppe’s history has been closely linked to the sea since the city’s origin.”

In a magnificent, absorbing retrospective of Sickert (the most substantial such survey in almost 30 years) which is on until September 18, 2022, Tate Britain presents a lucidly annotated visual biography of this distinctive and assertive character. He moved in the circles of Monet, Camille Pissarro, Renoir, Degas, Paul César Helleu (1859-1927) who painted portraits of society women of the Belle Époque, Beardsley, Whistler, and Charles Conder (1868-1909) a Briton who loved French art. Such luminaries, in addition to young painters from Sickert’s Camden Town group of artists who from 1911-13 were exploring new ways of representing city life, shared his fascination with Dieppe.

He was given the soubriquet “the Canaletto of Dieppe” by his friend the painter and writer Jacques-Emile Blanche who lived near the town. Blanche was acquainted with Degas, Manet, and Renoir so his opinion is worthy of note, although Sickert was overall not one for expansive cityscapes, landscapes, and the great outdoors.

Among the huge number (150) of his works from 70 public and private collections on show, it could be said that there is no one stand-out painting of the kind that would glitter in any exhibition of Van Gogh, Degas, Renoir or Monet – his is not the flashiest of techniques – but the great strength of this show is that it is held together by the broad cultural and social dimensions he explored on the canvas over six decades, and the artistic links between Britain and France that he represented.

Both in Dieppe and in London, the music hall took centre-stage for him, an unsurprising enthusiasm given that as a young man he was an actor, and he was just one of several artists and members of fashionable society attracted by the accessibility of Normandy from southern England. Born in Munich, Sickert moved with his family to England when he was eight years old. His father was an artist, introducing him to the work of French and British practitioners, and he switched from the stage to art in 1882,

Sickert was attracted to Dieppe’s arcaded waterfront, its cafés and its architecture including its grand hotel and the churches of St Jacques and St Rémy, with the main square dominated by native son Admiral Abraham Duquesne (1610-1688), who trounced the combined fleets of Spain and Holland in 1676 in two engagements off Sicily. Add to that its cute little shops, and all the ingredients were there for him to begin to saturate the artistic possibilities of the town.

L’Hôtel Royal on the seafront was one of Sickert’s favourite subjects, and he made an affectionate composition of its grandeur showing strolling figures on its splendid lawns, as the sky glowed pink, in 1894. With flags flying, there is a holiday or festival atmosphere, but there are signs that the building’s façade is ageing, and in fact at the end of the 1900 summer season the hotel was demolished, to be rebuilt the following year.

Another English visitor, Arthur Symons (1865-1945) referred to the physical state of the hotel in his poem At Dieppe:

One stark monotony of stone / The long hotel, acutely white/ Against the after-sunset light / Withers greygreen / and takes the grass’s tone.

Sickert’s came to the Normandy port on his honeymoon with his first wife Ellen Cobden in 1885, producing harbour and beach scenes, influenced by James McNeill Whistler, for whom he was an assistant. Sickert wrote glowingly of Whistler’s technique: “He will give you in a space nine inches by four an angry sea, piled up, and running in, as no painter ever did before. The extraordinary beauty and truth of the relative colours, and the exquisite precision of the spaces, have compelled infinity and movement into an architectural formula of eternal beauty. Never was instrument better understood and more fully exploited that Whistler has understood and exploited oil paint in these panels.” Such was Whistler’s 1893 oil painting on wood, The Bathing Posts, Brittany, pleasingly included in this exhibition.

Sickert’s admiration of Whistler is demonstrated by Tate by the adjacent placing of paintings by both artists, including Whistler’s A Shop of 1884-90 and Sickert’s A Shop in Dieppe of 1886-8 as he developed his handling of light and shade, and by Whistler’s 1895 portrait of Sickert. Among small pictures by Sickert of shop fronts is The Red Shop (The October Sun) from around 1888, with its brown-ochre-gold colour scheme and vermillion contrasts.

In that critical year of 1885, when he stayed at the home of Blanche, he got to know better Degas, whom he had met in Paris a couple of years earlier and who encouraged him to record with his brush audiences at the café-concerts. Sickert eagerly took note of Pissarro’s views of Dieppe and enjoyed walking around the harbour, taking his sketching pencils on his evening visits to a music hall on the Quai Henri IV.

In addition to Symons, writers who visited in the summer season included Oscar Wilde, Aubrey Beardsley, and Max Beerbohm. Especially touching is Sickert’s full-length portrait in tempera in 1894 of Beardsley. The curators say it is likely that the picture shows Beardsley walking through Hampstead Church graveyard after attending the unveiling of a memorial to John Keats. Beardsley was suffering from tuberculosis, the same disease which had killed Keats. The painting was published in the radical journal of the arts The Yellow Book that same year when Beardsley was its art editor.

The exhibition compares Sickert’s concert hall paintings with the1876 representation by Degas of the ballet scene from Meyerbeer’s opera Robert Le Diable (a picture bequeathed to the Victoria and Albert Museum by the 19th century art collector, grain trader and London stockbroker Constantine Alexander Ionides). In his oil painting on canvas, Degas shows the Ballet of the Nuns, in which ghosts of nuns shrouded in gossamer veils and white dresses rise from their tombs. This portrayal of movement, the effect of light on stage, and the innovative inclusion of the orchestra influenced Sickert in several of his works, say the curators.

The exhibition has some 30 paintings and drawings of night-life performers and audiences captured with immediacy and intimacy, often from unusual angles, in halls in London and Paris, including The Old Bedford 1894-5, Gaité Montparnasse 1907, and Théâtre de Montmartre c 1906 and includes performers such as Minnie Cunningham (originally exhibited with a quote from one of her songs, “I’m an old hand at love, though I’m young in years”) and Little Dot Hetherington, who famously sang “The Boy I Love is up in the Gallery.”

The French notably Edouard Manet and Degas had been ahead in the genre, and it took a while for the British art world to catch on. Even when cinema, radio and recorded music became all the rage, Sickert never lost his interest in theatrical subjects.

Musical-themed compositions by Sickert include one of the prominent conductor Eugene Goossens from 1923-4; sketches of brass and wind instrumentalists from 1922-23; and Brighton Pierrots from 1915, pervaded by the melancholy of the early stages of World War I. The last-named shows vaudeville entertainers on the seafront under the setting sun and artificial stage lights. Many of the deckchairs are empty, hinting at the absence of men serving in the war. The gunfire of the Western Front could sometimes be heard from the south coast of England. Quite a contrast to the earlier gaiety of the music halls.

Sickert left Dieppe at the outbreak of World War I, and the fighting in France kept him away until 1919. He planned to set up home there, but Christine Angus, whom he had married in 1911, was struggling with tuberculosis and she died in 1920. He continued to live in Dieppe until returning to London in 1922.

Later, in 1930, Sickert painted The front at Hove subtitled Turpe Senex Miles Turpe Senilis Amor which means in Latin ‘an old soldier is a wretched thing, so also is senile love.’ This implies that advances by a man to a young woman beside him would be in vain, as a dilapidated quarter of the town underlines the meditation on the ageing process.

An important section of the exhibition covers his most controversial phase, of his nudes of working-class women, presenting them in often squalid homes. They were far from the classical trope of the nude, far from alluring figures: there is a raw and disturbing power to them. Sickert concentrated on the patterns created on their flesh by light through a window. In 1910 he wrote: “The chief source of pleasure in the aspect of a nude is that it is in the nature of a gleam – a gleam of light and warmth and life. And that it should appear thus it should be set in surroundings of drapery and other contrasting surfaces.”

These nudes drew on earlier studies by Bonnard and Degas and were admired in Paris when he exhibited them in 1905, but scandalised British critics saw them as immoral references to low-class prostitution. The critics failed to see that Sickert was at the head of a major innovation in British painting: Lucian Freud (one of whose works is on display) and Francis Bacon later followed in his footsteps in their treatment of the nude. Tate raises the point that more recently, critics and viewers have asked if Sickert’s paintings objectify women,

Sickert was grimly fascinated with what was known as the Camden Town Murder, the killing in 1907 of 22-year-old Emily Dimmock in her flat not far from where he lived. His Camden Town Murder series were seen as narratives of the events – which at one stage even led to false accusations that he was Jack the Ripper, who carried out serial killings in Whitechapel during 1888.

Sickert was interested in the emotional connections in his scenes rather than illustrating the murder of Dimmock, and gave some of this paintings alternative, ambiguous titles such as What Shall We Do for the Rent? Other domestic scenes such as Ennui of 1914 and Off to the Pub in 1911 continued this exploration of complex modern relationships.

In his final years, he seized on what was becoming celebrity culture, with larger paintings based on press photographs, including images of Amelia Earhart’s solo flight across the Atlantic and Peggy Ashcroft in a production of As You Like It. This was an important precursor to the transformation by pop art of images from the media.

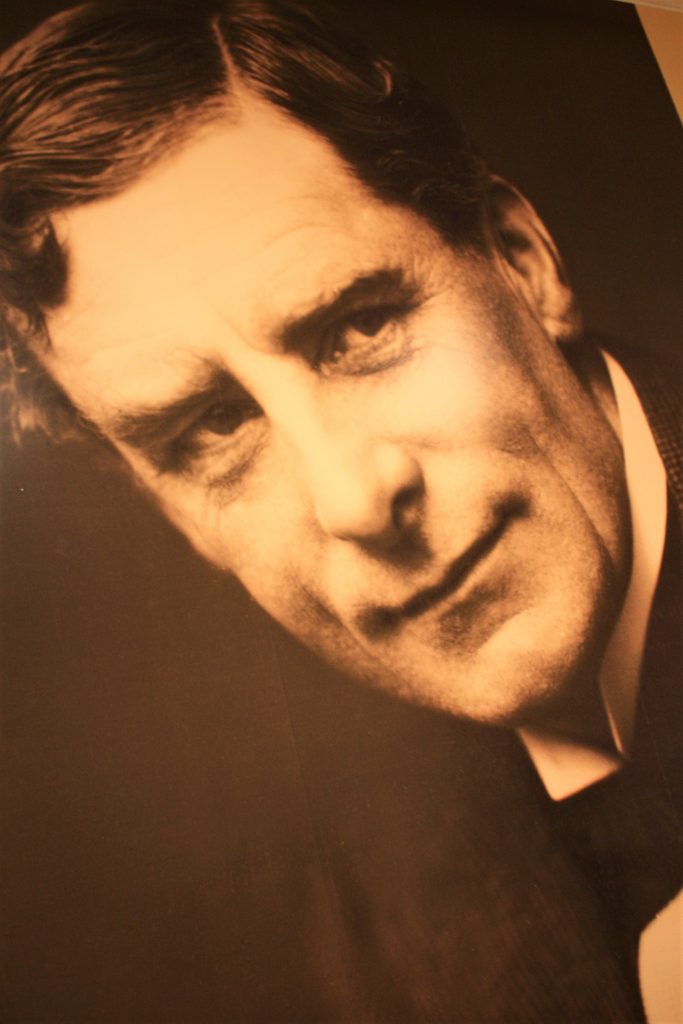

Ten self-portraits, from the start of his career to his final years have for the first time been brought together from collections including the National Portrait Gallery in London, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, and the Art Gallery of Hamilton in Canada.

Meanwhile… the port of Dieppe flourishes, with offshore wind energy adding to the activities which Sickert knew: cross-Channel traffic, general commerce, fishing, and leisure sailing.

The exhibition Walter Sickert is organised by Tate Britain in collaboration with the Petit Palais, Paris. It is curated with pithy wall labelling and an enlightened hang by Emma Chambers (curator, modern British art, Tate Britain), Caroline Corbeau-Parsons (curator of drawings and conservatrice des arts graphiques at Musée d’Orsay and former curator of British art of 1850-1915 at Tate Britain), the late Delphine Lévy (founding director of the institution Paris Musées which comprises 14 museums owned by the City of Paris), and Thomas Kennedy (assistant curator, modern British art, Tate Britain). Ms Levy sadly died suddenly at the age of 51 in 2020, while working on the project.

Picture captions in detail:

L’Hôtel Royal, Dieppe1894. By Walter Sickert. Sheffield Museums Trust.

The Red Shop (or The October Sun) c 1888. By Walter Sickert. Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery, Norfolk Museums Service.

Brighton Pierrots 1915. By Walter Sickert. Tate, Purchased with assistance from the Art Fund and the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1996.

Aubrey Beardsley. By Walter Sickert. Tate. Purchased with the assistance from the Art Fund 1932.

Gallery of the Old Bedford 1894-5. By Walter Sickert. Purchased by the Walker Art Gallery in 1947.

L’Eldorado c 1906. By Walter Sickert. The Henry Barber Trust, Barber Institute of Fine Arts, Birmingham University.

Scene from Robert Le Diable. By Degas. Victoria and Albert Museum bequeathed by Constantine Alexander Ionides.

Walter Sickert. Self-portrait c 1896. Leeds Art Gallery © Bridgeman images.

Eugene Goossens conducting. 1923-4. By Walter Sickert. Daniel Katz Ltd, London.

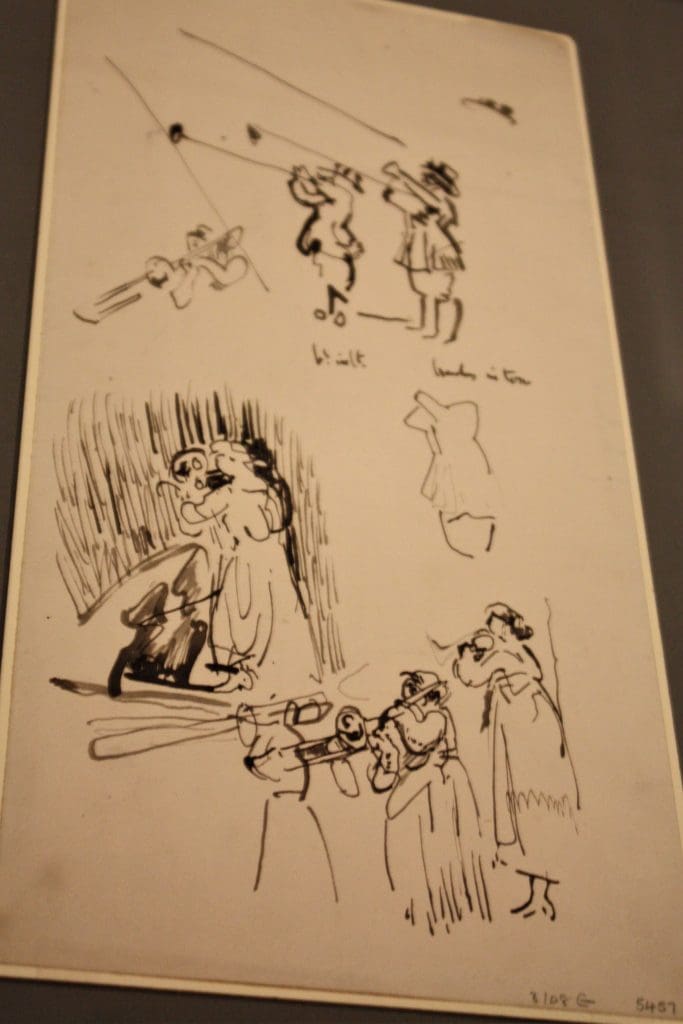

Brass and wind instrumentalists c 1922-3. By Walter Sickert. Walker Art Gallery.

The exhibition Walter Sickert is at Tate Britain until September 18, 2022.