By James Brewer

An intriguing dual exposure — of the radical work of two spiritualist-inspired early 20th century artists dedicated to a “higher plane” – is drawing crowds at Tate Modern.

Both the Amsterdam-based painter Piet Mondrian and Stockholm’s lesser-known Hilma af Klint began their careers by drawing naturalist pictures outdoors and indoors. Mondrian, who had an artistic attachment to the scenic dunes and seascapes of the Dutch coast, went on to make his international mark with something quite different: memorable, geometric abstractions influenced by spiritual symbolism. In Sweden, af Klint professed to receive messages by séance to produce pathbreaking allegorical imagery ahead in time of leading abstractionists elsewhere such as Kandinsky. She envisaged her largest canvases monumentally hanging in an all-religions temple, but those remained at her request in the archival shadows for many years after her death in 1944, emerging only in one retrospective at Moderna Museet in Stockholm in 2013 and another at the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum in New York in 2018, which set attendance records there.

Belatedly, a London spotlight has been shone, by the Tate, on Hilma af Klint “in the company of” Piet Mondrian, exploring how they co-incidentally engaged with spirituality and mysticism, even though they never met and probably never knew of each other. Tate has challengingly paired the unconventional protagonists to build a picture (from 250 exhibits) of the depth of resonance between them.

The show underlines how the swirling currents of scientific enquiry impacted intellectuals a century and a quarter ago. Technologies such as the microscope, radiography and photography were calling into question classical forms of human perception and thus of representation through artworks. They brought evidence of worlds invisible to the human eye, and of the bending and intertwining of time and space. In many artistic circles, there was both a clash and connection of technology and spirituality, leading to interpretations that were cryptic in many ways.

Among those who turned to esoteric movements as a way of reconciling long-established religion with the modern world were af Klint and Mondrian, inventing their own language of abstract art. Thus, enveloping much of the exhibition is the influence of theosophy – the word is derived from the Greek for the wisdom of the Gods: theos (god) and sophia (wisdom). Its teaching, considered outlandish by most intellectuals these days, is based on mystical insight, spiritual emancipation, and the reincarnation of the soul. Members believe that the soul is distinct from the body and can travel on the astral plane beyond the physical world. Its aims include “to investigate the unexplained laws of nature and the powers latent in man.”

Mondrian and af Klint travelled in their heads on parallel routes, seeking higher guidance amid the stars. Had they lived in 2023, they would surely have been in awe of the extra-terrestrial observatory, the James Webb Space Telescope, as it heightens galactic discoveries and insights into energy and matter. What would they have made of the phenomenon of the God-like machines of Artificial Intelligence with its touted approximations to sentience?

In 1904, af Klimt joined the Stockholm lodge of the Theosophical Society. while Mondrian joined the society in Amsterdam five years later. In his sketchbooks of 1912-14 Mondrian wrote: “All religions have the same fundamental content; they differ only in form. The form is the external manifestation of this content and is thus an indispensable vehicle for the expression of primary principles.” af Klint was totally in tune with that analysis.

So, what of the artworks? A visitor strolling through the gallery will adjust their focus to take in the sometimes-otherworldly aspects of the displayed objects, which vary in scale and intensity from the microcosm (Mondrian’s drawings of bacteria, and af Klint’s interest in the atom as akin to a solar system with orbiting electrons) to the macrocosm of the heavens. To express the ‘universal,’ af Klint and Mondrian both experimented with the dynamic relationships of form and colour.

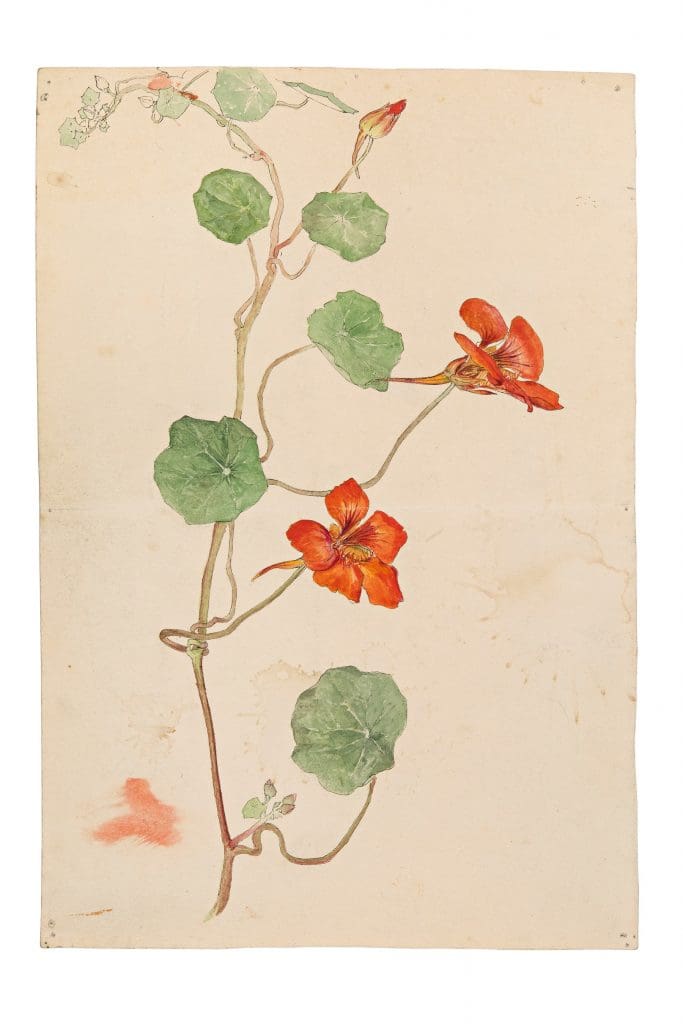

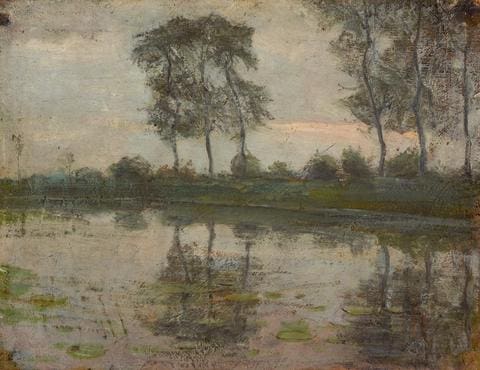

Both artists emerged from a landscape tradition of the late 19th century; in the case of Mondrian, we are reminded of his affinity with nature, from his early botanical drawings in which he loved depicting single flowers – such as chrysanthemums and lilies, using variously watercolour, crayon, charcoal, oils, and pastels. These are rarely exhibited paintings of the kind that he continued to create throughout his life. That he became best known for his geometrical abstractions is ironic as it is well known that nature abhors a straight line.

Born in Amersfoort in 1872, Mondrian at the age of 20 moved to Amsterdam where he studied at the Royal Academy of Visual Arts. He was attracted like his contemporaries to the shores of the Dutch province of Zeeland, particularly the historic town of Domburg, a resort on the Walcheren peninsula, where artists revelled in its landscape of expansive beaches and the quality of its light. His craftsmanship bloomed as he experimented with colour, style and technique.

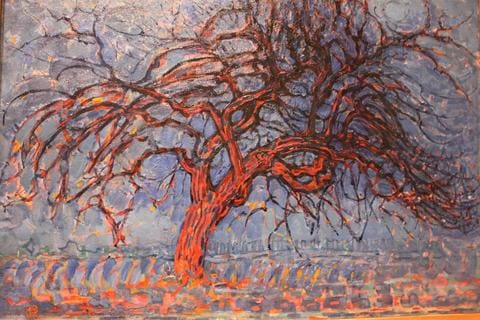

When Mondrian visited Domburg for the first time in 1908, he stayed at the summer residence of art collector and patron Marie Tak van Poortvliet and her close friend, the avant-garde painter, graphic designer, and stained-glass artist Jacoba van Heemskerck (1876-1923). He made sketches of a distinctive tree in their garden, which served as preliminary studies for oil paintings including Evening: The Red Tree, in which he brought out the intense reds and blues that would appear just before nightfall. He would return to the subject of the tree, the branches and roots of which in theosophy have symbolic connections with the visible and the spiritual universe. Mondrian tutored van Heemskerck who shared his interest in theosophy and while maintaining her individuality she echoed element of his style.

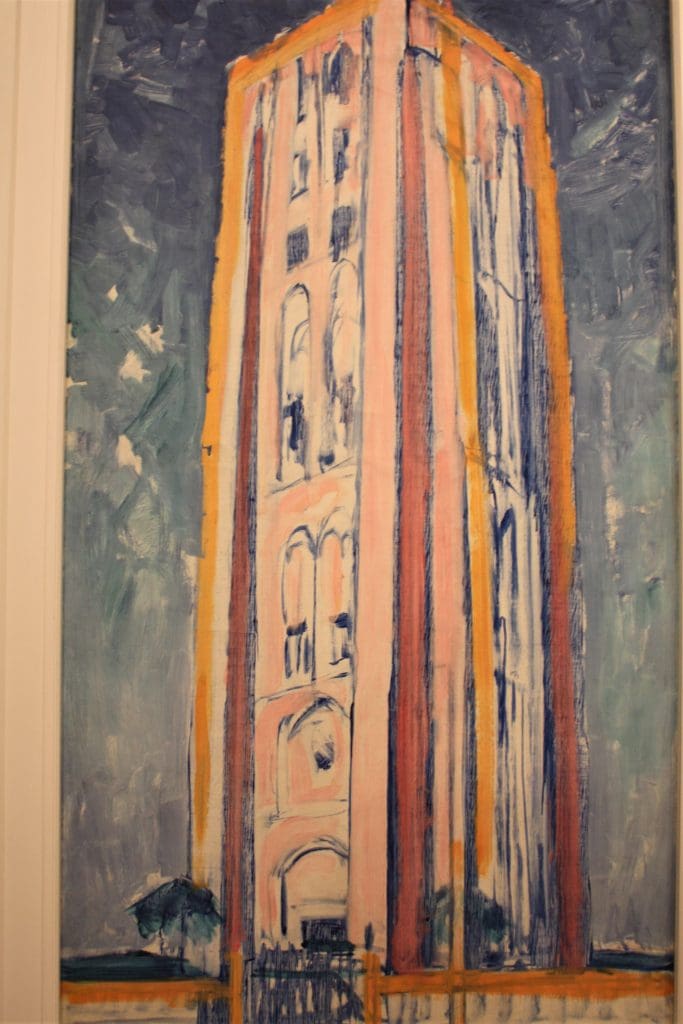

Still in Domburg, Mondrian gradually refined his images of the town’s towers and sea views until they shaded into abstraction. His study of the towers led him to the focus on horizontal and vertical principles that are characteristic of his abstract work. Searching for artistic forms to express fundamental life-processes, he set out to reduce painting to its basic principles, removing individual aspects (which he called ‘tragic’) to express the ‘universal.’ He saw the verticals as the ‘male’ principle, representing the spiritual, and the horizontal as expressing the ‘female,’ material principle. His goal was to ‘plastically express’ a universal harmony based on the balance of oppositional forces. During this period, he painted the Evolution triptych of 1911 which has been seen to represent humanity’s progress from the physical towards the spiritual realm.

His abstracts are thus full of intended meaning.

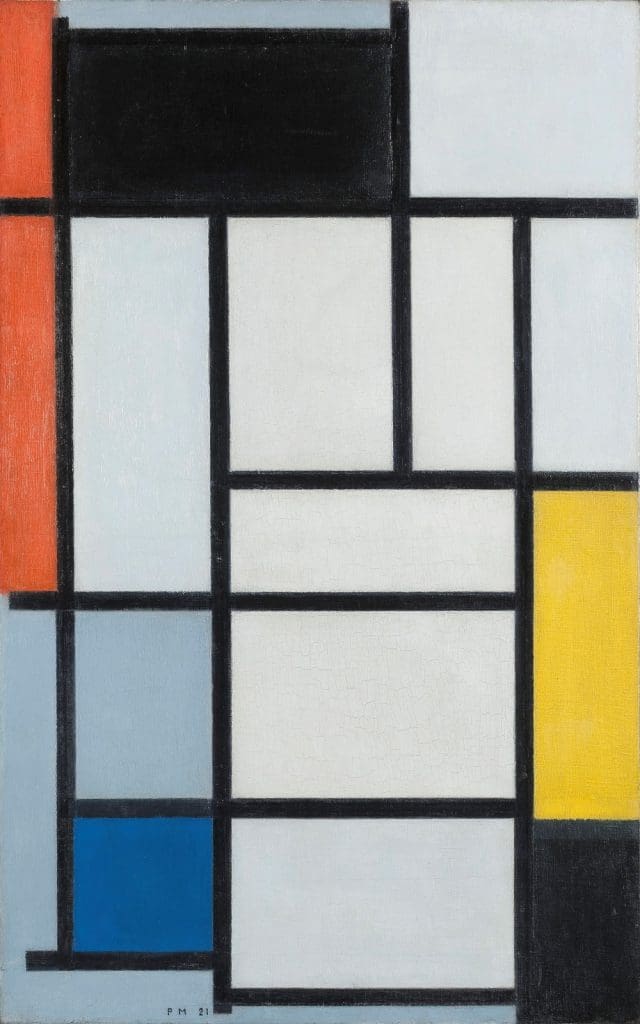

In 1917, he co-founded De Stijl, a movement which embraced basic visual elements such as geometric forms and primary colours. In his compositions of 1918 and 1919, Mondrian used a regular grid but created irregularities using colour, engendering a sense of rhythm and liveliness – to regard his work as detached from life oversimplifies its complex relationship to the world, contend the curators.

To Mondrian, the “deepest essence of art” was always to make “the beauty of life” visible, tangible and, most of all, perceptible. He wrote in 1919: “The natural does not have to be a certain depiction. At the moment I am working on a reconstruction of a starry sky, but without its natural ingredients.” This would be “a reconstruction according to the spirit.”

Mondrian emigrated to New York in 1940, where he died four years later.

Hilma af Klint was born in 1862 in Solna, a municipality in Stockholm. She became one of the first women to study at the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts. Alongside her work as a professional artist, af Klint (1862-1944) was a medium – she wrote 27,000 pages of notebooks about the occult – and believed that some of her paintings were commissioned by higher powers. Through theosophy and the work of a prominent philosopher Rudolf Steiner, af Klint would have encountered the notion of an invisible, fourth dimension of space. “My mission, if it succeeds, is of great significance to humankind,” she wrote in 1917. “For I am able to describe the path of the soul from the beginning of the spectacle of life to its end.”

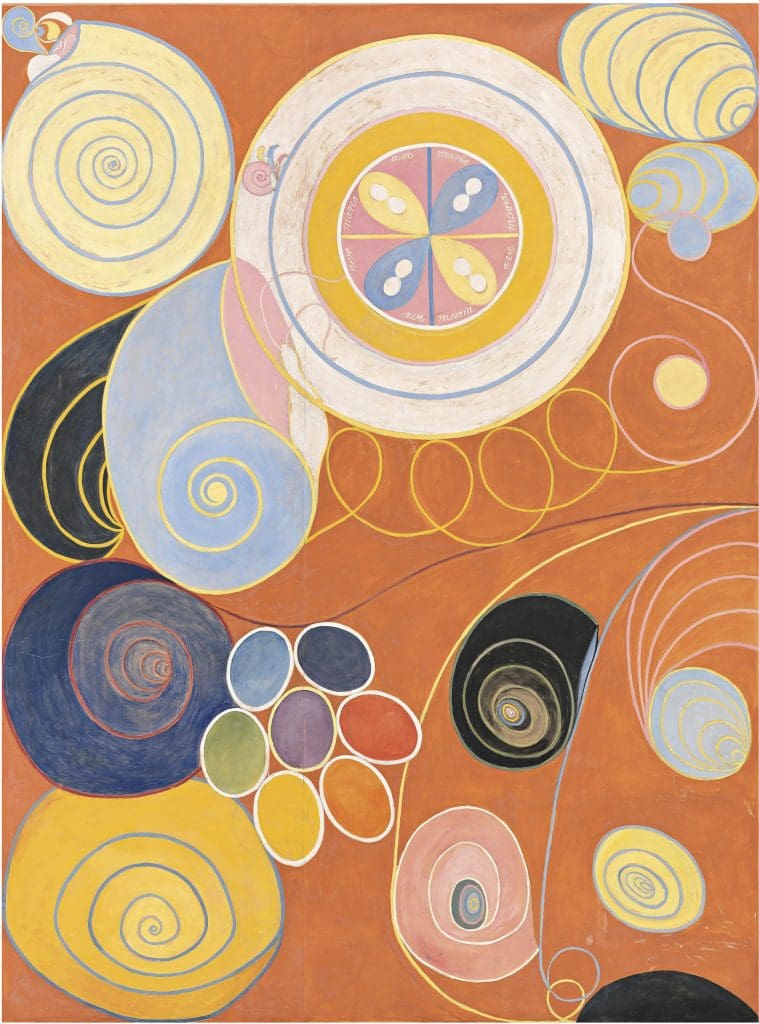

Among the largest presentation of Hilma af Klint’s work in the UK to date are all ten of her ambitious paintings – each canvas is 328 x 240 cm – from the 1907 series The Ten Largest, which fill one room, leaving spectators in awe. In 1896 af Klint had joined The Five (de Fem), a group of women artists interested in spiritualism, the natural world, and developments in science. During one of their séances, she believed that she was commissioned by a spirit to create a body of work “on an astral plane” to “proclaim a new philosophy of life.” She was to work on “ten paradisaically beautiful paintings” that would “give the world a glimpse” of the stages of life from childhood to old age. They are emblazoned with organic motifs and abstract geometries. Botanical forms morph into abstract ones, and the snail – representing the processes of growth and evolution – is reflected in a logarithmic spiral.

Such paintings were to be hung as a “beautiful wall covering” in a spiral-shaped temple, as ascending through the temple would be to move towards a higher state of being. In the exhibition is a model of such a temple. The artist described how as a medium, shapes, colours and compositions sprang into her mind. The Ten Largest are part of The Paintings for the Temple, a total of 193 works. Given the size of the works, it is likely that she painted each large canvas while it was lying flat on her studio floor.

From 1905, af Klint had begun her secret succession of mystical paintings, which she insisted should not be seen in public for at least 20 years after her death. In 1907, this included the Eros series, named after the Greek god of love, but she differs from the classic representation of Eros in appearing to balance opposing ‘male’ and ‘female’ forms. These pink-hued works take up the theme of polarity between male and female as the driving force of evolution. The diagonals evolve into forms reminiscent of flowers, leaves or ovals.

From Evolution of 1908 are seen examples of the Seven-Pointed Star Series. Seven is a sacred number in many cultures, associated with divine order, and the eternal harmony of the universe. In theosophy the star cluster, known as the Seven Stars or the Pleiades, is viewed as transmitting spiritual energy that eventually reaches the human plane.

Notable are af Klint’s references to the swan, an occult symbol of unity, discussed extensively by the theosophist activist Helena Blavatsky, who claimed to have psychic powers. The Swedish artist owned a copy of Blavatsky’s book The Secret Doctrine. The arc towards an eventual state of reconciliation in The Swan might have been af Klint’s response to massive political and social upheaval. She wrote: “Where war has torn up plants and killed animals, there are empty spaces which could be filled with new figures, if there were sufficient faith in human imagination and human capacity to develop higher forms.”

Both artists in the show wanted to express the interconnectivity of art with all forms of life. Seen from today’s perspective of environmental and planetary concerns, their contributions have become in the hands of the curators a conversation rooted in the present.

Captions in detail:

Composition with Red, Black, Yellow, Blue and Grey, 1921. By Piet Mondrian. Kunstmuseum Den Haag.

The Ten Largest, Group IV, No. 3, Youth, 1907. By Hilma af Klint, Courtesy of The Hilma af Klint Foundation.

The Ten Largest, Group IV, No. 7, Adulthood, 1907. By Hilma af Klint, Courtesy of The Hilma af Klint Foundation.

Red Amaryllis with blue background, 1909–1910. By Piet Mondrian. Private Collection.

Botanical Drawing, c 1890. By Hilma af Klint. Courtesy of The Hilma af Klint Foundation.

The Gein: Trees along the water c 1905. By Piet Mondrian. Kunstmuseum Den Haag.

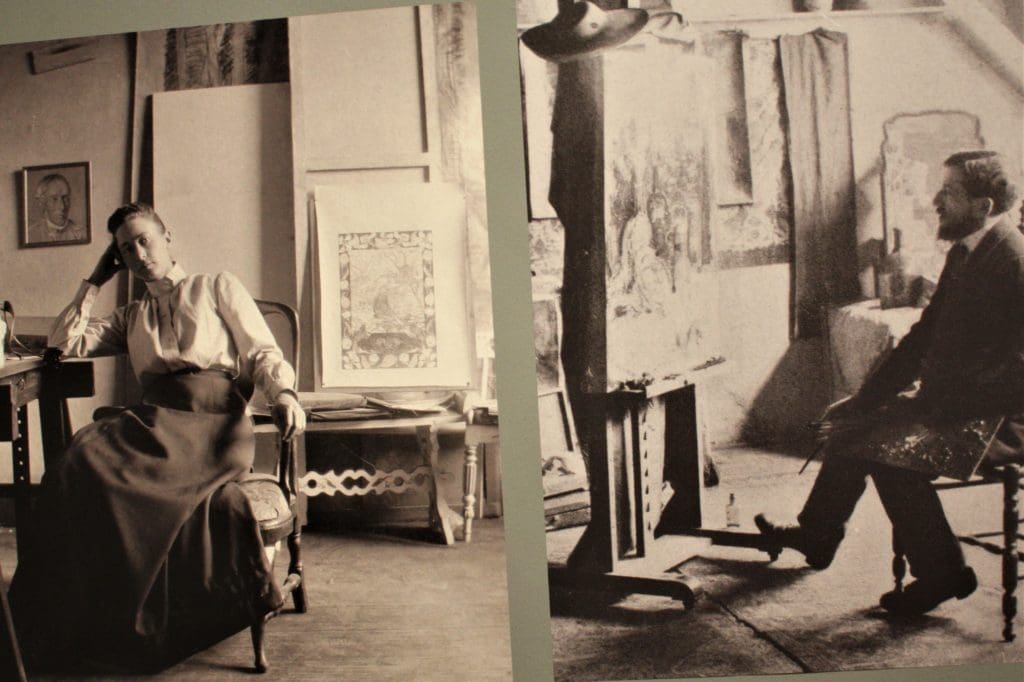

Hilma af Klint in her studio, Stockholm, 1895. Hilma af Klint Foundation; Piet Mondrian in his studio, Rembrandtsplein, Amsterdam. March 1906. Netherlands Institute for Art History.

Poppy. Undated. By Hilma af Klint. Watercolour and ink on paper. Hilma af Klint Foundation.

Evening: The Red Tree 1908-10. Oil on canvas. By Piet Mondrian. Gemeentemuseum Den Haag.

Lighthouse at Westkapelle, 1910. By Piet Mondrian. Oil on canvas. Kunstmuseum den Haag. Bequest Salomon B Slijper.

Portrait of Piet Mondrian. 1909. Photo facsimile. Netherlands Institute of Art History.

The Evolution, The WUS/Seven-Pointed Star Series, Group VI, No.15, 1908. By Hilma af Klint. Courtesy of The Hilma af Klint Foundation.

The Swan, the SuW/UW series, Group IX: Part 1. No 1. 1914-15. By Hilma af Klint. Oil on canvas. The Hilma af Klint Foundation.

Hilma af Klint and Piet Mondrian: Forms of Life is curated by Frances Morris, Tate Modern director; Nabila Abdel Nabi, curator, international art, Tate Modern; Briony Fer, Professor of art history, UCL; Laura Stamps, curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, Kunstmuseum den Haag, with Amrita Dhallu, assistant curator, international art, Tate Modern.

The exhibition is organised by Tate Modern and Kunstmuseum Den Haag. It runs until September 3, 2023.

It is presented in the Eyal Ofer Galleries, named after the chairman of Monaco-based Ofer Global, which is active in shipping, real estate, technology, banking, energy and other investments, with over 30,000 employees. He is on the board of Royal Caribbean Group. Mr Ofer established the group’s shipping division, Zodiac Group, in the 1970s alongside his father, the late Sammy Ofer, and it now operates a fleet of more than 180 vessels worldwide. The Eyal Ofer Family Foundation in 2013 donated £10m to support the expansion of Tate Modern.