By James Brewer

Black was the new black for the prolific artist John Singer Sargent. He portrayed his sitters in bold dark fabrics and was unafraid to ‘order’ to a complete change of dress colour to help materialise the images he wanted.

He is a forefather of the Instagram age. Sargent (1856-1925) and the women and men he painted paid elaborate attention to how well each outfit would translate to the canvas, manipulating the messages to send to wider society. The rapport between fashion and painting was well understood: a French critic declared that “there is now a class who dress after pictures, and when they buy a gown ask, ‘will it paint?’”

Collectively, Sargent’s portraits make for a radiant tour of fashionable high society at the turn of the 20th century, but it was one daring black dress that brought him some of his greatest fame, and infamy. His 1884 portrait of a socialite named Amélie Gautreau, dressed in a close-fitting black evening gown affronted some critics who saw it as erotically charged, and the title of the work was later changed to Madame X.

The intriguing painting turned out have a more long-lasting legacy than Sargent could have imagined, becoming a precursor of the “little black dress” phenomenon that endures to this day. Since the late 1920s especially, Hollywood and stage stars including Edith Piaf, Audrey Hepburn, Marilyn Monroe, Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, and Maria Callas have followed the fashion, as did Diana, Princess of Wales, in 1994 in an off-the-shoulder figure-hugging number.

Sargent and Fashion at Tate Britainspells out brilliantly how he in effect transformed himself into a stylist to craft the image of the sitters, with whom he often had close friendships. He once said, with only a little exaggeration, that he regarded himself as a “dressmaker as well as a painter.”

While there is little revelation of any psychological depth of the sitters nor many hints of narrative in the results, that reflects the social context and the milieu in which the artist moved. Sargent was using fashion to testify to the self-assurance and aura of a procession of non-shrinking violets – prosperous members of the bourgeoisie. Usually soberly suited himself, he regularly chose the striking outfits of his patrons, sometimes initially against their wishes, or steered the way they were worn,

Organised in collaboration with the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, a city with which Sargent was closely connected, the exhibition highlights 60 paintings – works drawn from the Tate and the Boston museum’s extensive collections, and rare loans, an awesome number of which are life-size. Lending the experience extra pizzazz are a dozen period dresses, fans and other accessories, well preserved after over a century and many of which were worn by the sitters. Several of the garments are ‘reunited’ for the first time with portraits of their wearers.

Sargent, born in Florence, Italy, to American parents, could take more than usual creative liberties with portraits that were not commissioned, such as his distinctive 1883-4 masterpiece of the glamorous Mme Gautreau (1859–1915), the Louisiana-born wife of a Paris banker. Sargent had persuaded her to pose, saying he would make “an homage to her beauty.” Admired in Parisian circles for her attractive appearance, which she enhanced with striking gowns and pallid, slightly bluish make-up, Mme Gautreau is depicted in the popular perception of her as “a living statue.” The designer of her satin and velvet dress has not been identified, although she often bought clothes from the elite Paris couture house Maison Félix.

What caused a stir at the 1884 Paris Salon was that one of her jewelled dress straps was shown teasingly slipping from her shoulder. Sargent insisted he painted her “exactly as she was dressed” and she described the portrait in a letter to a friend as a masterpiece. The poet and novelist Judith Gautier, a friend of and a sitter for Sargent, insisted it was “the precise image of a modern woman scrupulously drawn by a painter who is master of his art.”

Was the problem that the portrait brought to prominence in the French capital two ambitious figures of North American origin (Gautreau and Sargent)? Detractors denounced the “the indecency” of the dress; the offending strap was subsequently painted-in more conventionally, but Mme Gautreau’s mother fretted over the cost to the reputation of Amélie, and Sargent left for England, his good name also questioned.

Sargent retained his portrait of Mme Gautreau until after her death in 1915, when he sold it for $1,000 to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. In a letter to the director of that institution, Sargent wrote: “I suppose it is the best thing I have done,” but he requested that the museum rename it so as not to rake up the scandal, and the lady became Madame X. Just as fascinating and with a certain cachet is an unfinished replica of the allegedly undignified original. That version, again with the right shoulder strap missing and with the dress incomplete at the base, was acquired by the Tate after his death. Perhaps he meant to add the strap in due course.

In the late 19th century, black dresses had become fashionable for women of all ages, although there was still an association with mourning. Sargent revelled in this change, as seen by the prevalence of black in his portraiture. Black was once described as “the most aristocratic colour of all” by Ukrainian American wood sculptor Louise Nevelson (1899-1988), who was among those who were captivated by its application in the visual arts. During the 1880s, Sargent painted almost half of his female sitters, of varying ages, in black gowns, and often against near black or dark brown backgrounds.

For him, black was not just black. Synthetic dyes introduced in the mid-19th century produced an intense black that enabled a new depth of colour. Sargent’s heroes included two 17th century masters of black, Spain’s Diego Velázquez and the Dutch artist Frans Hals, and he was surprised to learn that his friend Claude Monet worked without black.

Gallery visitors should not worry, though – the passion for black is far from monotonous or depressing – and Sargent has a dazzling facility to orchestrate contrasts of fabrics by wielding a luscious colour palette. There is so much to admire in the way he makes a dress melt into its folds, in the transparency of a sleeve. The curators guide us to the, so to speak, hidden wiring of his subjects.

To reinforce his rich visual language, Sargent often chose from the bespoke wardrobes of his sitters what they should wear. Even when women who arrived in his studio were in the latest fashions, he might seek to simplify and alter the details to bestow an entrancing freshness. One sitter wanted her young daughter to be painted in a green dress, but he said No, found a piece of pink fabric and styled it around the girl’s figure as though it were a dress: the result was a harmonious and sympathetic portrait in 1903 of Mrs Fiske Warren (Gretchen Osgood) with her eldest daughter Rachel. Mrs Warren, a member of a prominent Boston family, was an accomplished poet who had in Paris studied singing with Gabriel Fauré and drama with the great actor Benoît-Constant Coquelin (both friends of Sargent). The sittings are documented by photos In the exhibition.

Sargent’s love of music and theatre are seen in his settings, as with a portrait from his early career of Amalia Subercaseaux (1860–1930), wife of the Chilean consul and artist Ramón Subercaseaux. She is seated at a piano in the couple’s stylish residence on the Avenue du Bois de Boulogne.

From the start of the exhibition, we see how he skilfully handled clothing. A 1907 portrait of Lady Sassoon (Aline Caroline de Rothschild) overlooks the black taffeta opera cloak with discreet pink lining that she wore, “revealing how he pulled, wrapped, and pinned the fabric to add drama to the image,” say the curators, “just as an art director at a fashion shoot would behave today.” Sargent enjoyed a long friendship with the influential Sassoon family.

In 1904, he painted a portrait in Venice – the Grand Canal is just visible through a balustrade – of Lady Helen Vincent, Viscountess d’ Abernon (1866-1954) in a black satin evening gown. This is yet again an exuberant use of black, emphasised by her pink wrap, with a sufficiently revealing look that could be described as risqué. This society hostess was to become in wartime a nurse anaesthetist serving with the Red Cross in Europe, often dangerously close to the front. Before that, the sisters entertained frequently, including weekend house parties for a group of intellectuals known as ‘the Souls’.

Another society hostess, Mrs Charles Inches (Louise Pomeroy), sat for Sargent in Boston in 1887 during his first working trip to the US. In the exhibition she is partnered with the red velvet evening gown she wore. Louise Inches was a talented pianist who is said to have played duets with Sargent during sittings. When the painting was exhibited in Boston in 1888, a reviewer in the Boston Evening Traveller exclaimed it was “one of the most brilliant pieces of colouring that has been painted since the days of Titian.” The hauteur of the subject prompted another critic to write: “I think Mrs Inches looks as if she would bring you the head of Holofernes for the asking.”

A portrait in the UK for the first time displays the painter and photographer Mrs Montgomery Sears (Sarah Choate Sears) of Boston, and alongside is a dress by the House of the English Paris-based designer Charles Frederick Worth. Mrs Sears lent support to artists and musicians, including Sargent, and we see photographs of him at work. She collected pieces by French Impressionists and by Sargent, and approached him for a portrait in 1890, finally sitting for him nine years later. By that time, he had already painted her daughter Helen at age 6. Sarah took a photo of Helen wearing what appears to be the same dress and shoes, and Sargent observed: “How can an unfortunate painter hope to rival a photograph by a mother? Absolute truth combined with absolute feeling.”

Sarah loved colour, as witnessed by one of her lustrous evening gowns displayed near her portrait. The sleeveless dress with a low neckline is of bengaline, a shiny, ribbed fabric made from silk, or silk blended with cotton. It is adorned with hundreds of faux pearls, individually attached. Such gowns cost up to the equivalent in today’s money of £25,000.

Ena and Betty (Helena and Elizabeth), painted in 1901, were the eldest daughters of Asher Werthemer, a London art dealer and his wife Flora. He commissioned paintings of the entire family, making him one of Sargent’s most important patrons. The two women – note their seemingly elongated fingers, a feature of many Sargent oeuvres – posed in the drawing room of their home. Betty’s red velvet gown contrasts with Ena’s white damask finery. The picture was presented to the Tate in 1922 by the widow and family of Asher Wertheimer.

Amid cherry-coloured silk velvet filling half her picture of 1892 is Mrs Hugh Hammersley. Mary Hammersley hosted Sargent at her London home, alongside other artists including Walter Sickert and Augustus John. Her gown is trimmed with gold lace and her glittering standing collar is modelled after paintings of Rubens, “but the nervous intensity of the pose is wholly modern,” say the curators. Of sitting for Sargent, she recalled that “some days he would work the whole time without ceasing, as one possessed, whilst others were spent playing the piano, which he did charmingly.”

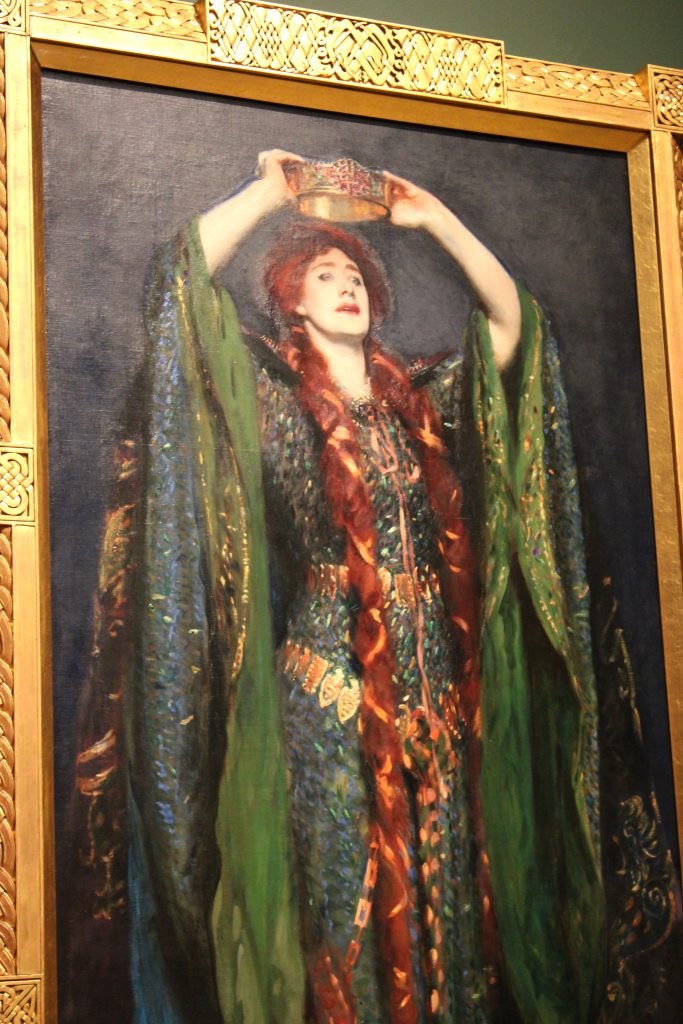

In addition to his wealthy clients, Sargent – always elated by visual spectacle – portrayed professional performers, including dancers, actors, and singers. One of the most eminent was the Shakespearean actor Dame Ellen Terry (1847-1928) of whom he crafted a magnificent image, currently lent by National Trust Collections, Smallhythe Place (The Ellen Terry Collection). She is pictured as Lady Macbeth in a spectacular costume (on display) sewn with iridescent beetle-wings, designed by Alice Comyns Carr and Ada Cort Nettleship. The project stemmed from Sargent’s exhilaration on seeing her on the opening night of December 27, 1888, of Henry Irving’s production of Macbeth at the London Lyceum. Typical of his unconstrained approach, he painted her in a scene which was not in the Bard’s script, placing a crown on her head following the murder of King Duncan. “From a pictorial point of view, there can be no doubt about it – magenta hair!” exclaimed Sargent. Seeing the work in progress, the Pre-Raphaelite Edward Burne-Jones offered suggestions which might account for the difference between the blues of the painting and the greens of the dress. Oscar Wilde, who saw Terry’s arrival at Sargent’s Chelsea studio, remarked: “The street that on a wet and dreary morning has vouchsafed the vision of Lady Macbeth in full regalia magnificently seated in a four-wheeler can never again be as other streets: it must always be full of wonderful possibilities.”

La Carmencita from 1890, depicts 21-year-old Spanish dancer Carmen Moreno, who performed in music halls across the United States, Europe, and South America. Sargent found her “bewilderingly superb” and saw her perform on many occasions in New York, where he painted her in a borrowed studio. She was renowned for her whirling routines – shown in original scratchy film footage close to Sargent’s painting of her which rejoices in her shimmering gold and white dress; and the dancer’s sparkling yellow satin costume adds to the splendour.

The exhibition features one of Sargent’s singular male portraits: Dr Pozzi at Home. from1881. The surgeon and pioneer of modern gynaecology Samuel-Jean Pozzi appears in a flamboyant red dressing gown and Turkish slippers, and viewers might be transfixed by his startlingly long fingers. Those tactile digits must have been a factor in him greatly impressing the women of Paris, including Sarah Bernhardt, and he was rumoured to have had an affair with Madame Gautreau (Madame X), among others. That was why he was nicknamed the love doctor. Aside from that, he was an art collector whom Sargent revered.

The regalia worn by Charles Stewart, sixth Marquess of Londonderry at the coronation of Edward VII is reunited with the painting to show how the artist conveyed rank and personality through clothing. The marquess is carrying the Great Sword of State dating from the 17th century which was in 2023 brought out as part of the coronation ceremony of Charles III.

Lead support for the exhibition with a generous donation came from the Blavatnik Family Foundation, and there was financial support too from the Terra Foundation for American Art.

The exhibition is curated by James Finch, assistant curator of 19th Century British Art at Tate Britain; and Erica Hirshler, Croll Senior Curator of American Paintings at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; with Chiedza Mhondoro, assistant curator of British Art at Tate Britain; Caroline Corbeau-Parsons, curator of Drawings at Musée d’Orsay; and Pamela A Parmal, Chair and David and Roberta Logie curator of textile and fashion arts emerita at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Captions in detail:

Gallery display of Madame X, 1883-84. Oil on canvas. Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Arthur Hoppock Hearn Fund, 1916.

Madame X. Study of Virginie Amélie Gautreau, born Avegno, c 1883. Oil on canvas. Tate. Presented by Lord Duveen through the Art Fund 1925.Tate, London.

Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth, 1889 (detail). Oil on canvas. Tate Britain, presented by Sir Joseph Duveen (the elder), 1906.

La Carmencita, 1890. Oil on canvas. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Photo © Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/ Patrice Schmidt.

Ena and Betty, Daughters of Asher and Mrs Wertheimer, 1901 Oil on canvas. Tate. Photo © Tate (Joe Humphrys).

Costume worn by La Carmencita, c.1890. Silk, net, beads, sequins. Private collection © Houghton Hall.

Mrs Joshua Montgomery Sears (Sarah Choate Sears), 1899. Oil on canvas. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Dress made from pearl-embroidered silk-based bengaline, c 1880 owned by Sarah Choate Sears. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Gift of Mrs JD Cameron Bradley.

Lady Sassoon, 1907. Oil paint on canvas. Private collection. Image © Houghton Hall.

Mrs Hugh Hammersley, 1892. Oil on canvas. Lent by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mr and Mrs Douglass Campbell, in memory of Mrs Richard E Danielson, 1998. Image copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence.

Dr Pozzi at Home, 1881. Oil on canvas. The Armand Hammer Collection, Gift of the Armand Hammer Foundation. Hammer Museum, Los Angeles.

Lady Helen Vincent, Viscountess d’Abernon, 1904. Oil on canvas. Collection of Birmingham Museum of Art, Alabama; museum purchase with funds provided by John Bohorfoush, the 1984 Museum Dinner and Ball, and the Museum Store.

Co-curator Erica Hirshler with painting of Mrs Charles E Inches (Louise Pomeroy), 1887, oil on canvas. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Anonymous gift in memory of Louise Brimmer, daughter of Mrs Inches.

Sargent is at Tate Britain until July 7, 2024.