The Deluge.

Dulwich Picture Gallery gives painter of genius Winifred Knights first retrospective 70 years after her death

By James Brewer

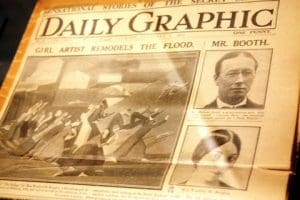

A “Streatham girl of 21” was prominently featured in the Daily Graphic (price one penny) of Tuesday February 8, 1921. “Girl artist remodels the Flood, ” ran the headline. This referred to “Miss Winifred Knights” and her prize-winning masterpiece The Deluge which the paper described as “the work of a genius.

The “girl” would be lauded by some of her greatest contemporaries for her purity of line in the spirit of Leonardo da Vinci, no less.

Daily Graphic story, April 1921.

Despite the accolades, the work of Winifred Knights (1899-1947) has been mostly neglected for years (although The Deluge is perhaps best known as part of the Tate collection), and the shameful disregard is bring rectified by a bold exhibition at Dulwich Picture Gallery, which will continue until September 18 2016. Winifred never had a dedicated exhibition during her lifetime, and her masterpieces have been brought together for the first time, supported by more than 70 of her preparatory studies, on which she lavished intense care.

The gallery has reintroduced her as one of the most thoughtful and original artists of the 20th century. The picture that emerges is of a woman of nobility of purpose and a superb craftsperson — even her unfinished paintings won prizes – and of the producer of work, as the gallery phrases it, which “embodies the fighting spirit of women artists at the time.”

Winifred Knights, self-portrait, 1920. Pencil on tracing paper. C Trustees of the British Museum.

As the curator, Sacha Llewellyn, says, “she was surrounded by strong women in her life, ” who served as models, consciously and otherwise, for her output, and as role models. She rarely portrayed male figures.

The Scottish artist Sir David Young Cameron perceived a heritage of draughtsmanship worthy of the highest praise for he “saw much of Leonardo da Vinci in Winifred.” She indeed admired and re-elaborated the output of the Quattrocento, the great Italian art of the 15th century, fitting its progressive elements into concepts of her own time and personal life.

She presents herself in all her paintings as a central protagonist, so these have become documents of what she is living through at the time, and the viewer is granted a rounded picture of her loyal and distinctive personality.

Winifred Knights was born in Streatham, the eldest child in an enlightened middle class family, with both parents believing strongly in women’s education as a pathway to individual freedom and independence. From 1912 she attended a girls’ school in nearby Dulwich where her artistic talent was manifest. Her first success came at the then male-dominated Slade School of Fine Art, where she originally thought to train for a career as a book illustrator, and examples of this pursuit are to be seen in the first gallery of the new exhibition.

Photo of Winifred Knights.

In her years at the Slade School from 1915-16 and 1918-20, she was fortunate to have tutors who stressed the importance of meticulous configuration including the use of scale drawings, full-size sketches and life studies. It was this determined “compositional purity” which was of great interest, said Sacha Llewellyn.

Before she was out of her teens, her social conscience was to the fore in her championing through her representations on paper and on canvas of the subject of women’s rights. This was partly because of her family background, in particular her close personal affinity to another wonderful woman, her aunt Millicent Murby. Millicent was treasurer of the Fabian Women’s Group, and as a member of the Women’s Trade Unions a campaigner for emancipation including equal pay and the right for married women to work; her writings had a great influence throughout Winifred’s life. Millicent is seen in Winifred’s 1917 pencil drawingPortrait of Millicent Murby.

The first of Winifred’s compositions to portray fraternisation of male and female workers was The Potato Harvest of 1918

Leaving the Munition Works, 1919. Watercolour over pencil on paper. Private collection.

Leaving the Munitions Works, from the following year, celebrates the female munitions workers who were drafted into factories, signalling although temporarily progress for women in their economic status and towards independence.

In 1919, A Scene in a Village Street with Mill-Hands Conversing was much more than the title indicated: a leading role is played by her aunt Millicent as a red-jacketed trade union inspirer for women to press for improved conditions, in this case at Roydon Mill, Essex. Winifred herself is in the scene, listening intently to the discussion. In this moving work, Winifred’s use of egg tempera, a medium of the Renaissance, is testament to the strong pull which study of that period was exerting.

Sacha Llewellyn says that the smooth surface, contemplative mood and harmoniously restricted palette employed by Winifred recall early Renaissance frescoes, adapted to everyday subjects from her own time.

The “missing” year at the Slade is explained by the shock of the Great War, which was shattering the way of life and the expectations of millions. Her home area of Streatham was a target of bombing raids, and she witnessed at first-hand one explosion which gave her a mental breakdown and the need to convalesce in the countryside. London had suffered the awful Silvertown explosion which shook the east of the city when 50 tons of TNT blew up at a munitions factory, killing 73 people and injuring 400 more. The blast was heard for many miles, with factories, docks and warehouses devastated.

Sacha Llewellyn, curator.

In 1920, Winifred secured a great advance in women’s recognition in the arts, in a determinedly male arena, and it reinforced the path she had trodden thus far. She was the first woman to win the Prix de Rome three-year scholarship in Decorative Painting awarded by the British School at Rome. This was the most important such award in the British Empire, with an allowance of £250 a year.

This put her name on the map, and there was endorsement from illustrious names, principally John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) the celebrated landscape painter and portraitist who had close links with Italy.

The Prix de Rome in 1920 was awarded for her canvas The Deluge, a compelling canvas which is to be seen, although this is not specifically stated, more as revulsion from the horrors of conflict than from flood. The Biblical deluge was frequently cited at the time as a metaphor for the Great War.

In this composition, the artist painted 21 men and women who are struggling to reach what they desperately hope will be the safety of a mountain, as they are threatened by the irresistible flood. Winifred draws herself as the central figure, amid a landscape of flattened perspective, a bleak no-man’s-land. Sacha Llewellyn said that the focus was on the victims fleeing an explosion, reflecting the trauma and sense of panic the artist had suffered during terrifying raids by Zeppelins, huge airships, over parts of London between 1915 and 1917. Streatham was hit by one in September 1916.

The Potato Harvest, 1918. Watercolour over pen and ink on paper. Private collection.

In this apocalyptic vision, there is thought to be an allusion to an 1874 poem by James Thompson, The City of Dreadful Night, which tells of London as a place of despair. The curator commented: “There is no message of hope; it is very much the idea of the artist’s trauma suffered during the war.” She had turned her back on religion after the death of her baby brother.

Perhaps the highpoint of the Dulwich exhibition, The Deluge is accompanied by numerous studies which underline the painstaking efforts taken to create the masterwork. Most fascinating is Compositional Study for the Deluge. The picture shows the influence of the war paintings of a previous generation of Slade students including Paul Nash, Stanley Spencer and CRW Nevinson. Her style around this time has particular resonances of Spencer, in particular his Zacharias and Elizabeth (1913–14) drawn from the Gospel of Luke.

Winifred designed and wore elegant clothes with loose bodice, and particular attention to shoes, was in demand herself as an artists’ model, and was courted by many of the male artists at the British School, Her five years in Italy was her glory, and Sacha Llewellyn says that she saw the country as a living landscape that revitalised her creative spirit. This led her to produce further dramatic work blending Renaissance technique with modernism.

Most significant is The Marriage at Cana, in which she appears several times as one of the wedding guests and the bride within a loggia, as does her future husband and Rome Scholar for 1922 Thomas Monnington, and former fiancé, Arnold Mason.

The Goose Girl, May 1918. Pencil and watercolour on paper. Collection of

Robin de Beaumont.

The meticulous planning of every scene is recorded in many preparatory studies. Even after two years labour, the work was unfinished, but members of the painting faculty reported that it they were “entirely satisfied with the manner in which she had fulfilled her duties as a scholar.”

Each student at the British School was required to submit a large-scale decorative painting to demonstrate that they had studied the great frescoes of Italy, and understood their technical excellence. Like many before her and since, Winifred loved the series Legend of the True Cross by Piero della Francesca at Arezzo. The Marriage at Cana has been lent to Dulwich by the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

Of her late Italian sojourn, Edge of Abruzzi boat with three people on a lake, was painted after Winifred and Thomas spent the summer of 1924 at Lake Piediluco, Umbria. The picture has Mélusine, a feminine spirit of sacred springs and rivers, in mind.

Her final composition from Italy was The Santissima Trinita, with a group of peasant pilgrims, and Winifred shown sleeping peacefully on the ground.

Despite all this success, and her work being highly sought-after by collectors, on her return to England in 1926 she once more came up against chauvinism. In 1928 she was awarded a prestigious commission to design an altarpiece for St Martin’s chapel in Canterbury Cathedral, on which she worked for five years, but it was in vain – it was in place for only a short while. The finished piece, Scenes from the Life of Saint Martin of Tours, is as most of her work autobiographical, expressing her anguish at giving birth to a stillborn son in January 1928. Among the onlookers in the scene are her mother who had suffered the distress of losing a baby son, and husband Thomas.

The outbreak of World War II was another blow. She became distraught and her only concern was for the safety of her surviving son. This brought her work to a standstill until 1946, a few months before she died of a brain tumour.

Sacha Llewellyn, a freelance writer and curator, and director at Liss Llewellyn Fine Art has approached her task with love and deep insight. She said of Winifred: “Like so many women artists, heralded and appreciated in their own day, she has disappeared into near oblivion.”

Although never part of the modernist avant-garde, she “engaged with modern-life subjects, breathing new life into figurative and narrative painting to produce an art that was inventive and technically outstanding. This exhibition, in bringing together a lifetime of work, will create an irrefutable visual argument that she was one of the most talented and striking artists of her generation.”

Winifred Knights (1899-1947) is part of Dulwich Picture Gallery’s programme of exhibitions devoted to critically neglected modern British artists.

All iimages © the Estate of Winifred Knights.

Caption to The Deluge, 1920. Oil on canvas, Purchased with assistance from Friends of the Tate Gallery 1989. © Tate, London 2016.