Dalí/Duchamp: Royal Academy reveals a deep dialogue

By James Brewer

In the April 1959 edition of ArtNews magazine, Salvador Dalí listed 13 reasons why a single title by Duchamp is “worth miles of pseudo-decorative modern painting.”

The flamboyant, absurdist-moustachioed Dalí was as handy and outrageous with the pen as with the paintbrush: the first artist-celebrity of his era.

Marcel Duchamp, 17 years his senior, set out too to blast away the cobwebs of the art world by confronting it with the shock of conceptual art.

Despite their diverging artistic and political paths, the two were long-standing friends. The Royal Academy of Arts compares and contrasts their careers in its remarkable exhibition Dalí/Duchamp.

It is the first presentation of the art of the two effervescent non-conformists as the kind of dialogue in which the two art heretics would have revelled.

The curators acknowledge that Duchamp (1887–1968) and Dalí (1904–1989) are usually seen as opposites in many respects, but they shared enough attitudes to art and life that drew them together. Among other facets, they brought their fascination with the erotic to the forefront of their activity, personal and artistic. Apart from the sexual allusions, they had a common interest in optics optical illusions and in found objects. It made for mutual admiration.

The King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes (verso with Paradise: Adam and Eve), 1912. By Marcel Duchamp.

Dalí felt impelled to bring creepy and vulgar motifs into many of his paintings.

Duchamp was fond of casually outraging ‘good taste.’ He is seen in a 1963 photo seated at a table playing chess with a naked Los Angeles author and “party girl” named Eve Babitz. He was 76 years old, she was 20. Apparently, Duchamp won most games, but Eve said that she triumphed in making her boyfriend jealous, which was what she had set out to do.

Chess was a big draw in the life of Duchamp. He saw it as a “visual form of movement” and even gave up involvement in the art world for the chessboard at one stage. Chess, science and sex were intertwined fascinations: he links sexual activity with electricity.

It was Duchamp’s painting of 1912, The King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes, which led to Dalí’s praise about it being worth as much as other modern paintings put together. At the time, it was common to refer to electrons being “built swiftly.” From that point, Duchamp found ways other than painting to express himself, searching for how to convey the idea of motion.

The dual-artist theme for the exhibition came from Dawn Ades, an independent art historian, and William Jeffrett of the Dalí Museum of St Petersburg, Florida. To accomplish the curation, they were joined by Sarah Lea and Desiree De Chair of the Royal Academy.

Prof Ades said that many people would have their prejudices alert before stepping into the four rooms devoted to the show, “but I think they will leave without them.” Still, visitors are warned to “please note, this exhibition contains some adult content.”

The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even. By Marcel Duchamp (reconstruction By Richard Hamilton).

Ms Ades drew attention to Duchamp’s 1911 painting of a coffee grinder, which saw him begin to draw in a much more technical manner. This work was not intended for public view, but is seen as a forerunner to the element identified as a chocolate grinder in his work The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) in which the bachelor grinds his own chocolate, considered by analysts a sexual metaphor.

Both men were egocentric, of course Dalí notoriously to excess, while Duchamp spent time putting together in a suitcase a miniature museum of his own work. Dalí was alleged by rivals to be so grasping that André Breton who expelled him from the Surrealists group nicknamed him Avida Dollars, an anagram of Dalí’s name. Dalí and Breton were politically opposite, for Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, Marquis of Dalí de Púbol was a supporter of the Franco regime; the Frenchman was satirical rather than political.

Although one was a showman and the other a more contemplative type, the two were united their humour and scepticism, which led them to challenge conventional views of art and life.

Covering what one gallery chief a little nervously called “virgin territory,” the display brings together 80 works, including some of Dalí’s most inspired and technically accomplished paintings and sculptures, and Duchamp’s novel assemblages and ‘ready-mades.’ It has film of the pranks of Dalí, vitrines with his photographs, and correspondence between the two artists.

Taking their friendship – they met through mutual contacts in the Surrealists group – as its starting point, it demonstrates the aesthetic, philosophical and personal links between them. They met in the early 1930s, and in 1933, Duchamp made his first visit to the fishing village of Cadaqués, near Dalí‘s home of Port Lligat, where they were photographed lying on the beach, playing chess.

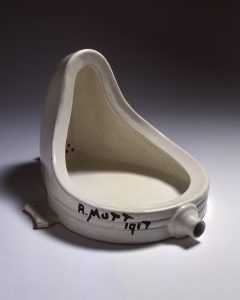

Each experimented initially with the artistic trends of their recent times, Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism and Futurism. Duchamp stopped painting on canvas in 1918 in favour of conceptual work such as his iconic Fountain, a ‘ready-made’ of a year earlier, nothing more than a porcelain urinal signed with the pseudonym R. Mutt, and submitted to the Society of Independent Artists. Then Duchamp parodied the Mona Lisa by adorning a postcard of the painting with a moustache and goatee, and writing L.H.O.O.Q. underneath, said to be an abbreviation for “She has a hot arse.”

Of a piece with that, although from 20 years later, is Dalí‘s Lobster Telephone, joining two objects that for him had aphrodisiacal connotations. He associated the lobster with erotic pleasure and pain, and in his works used the creature to cover the female sexual organs of his models. Dalí drew a close analogy between food and sex. In Lobster Telephone, the crustacean’s tail, where its sexual parts are located, is placed over the mouthpiece. For the 1939 New York World’s Fair, Dalí created a multi-media experience entitled The Dream of Venus, which included dressing live models in costumes of fresh seafood. The version of the work on show at the Royal Academy was inspired by the English poet and collector of Surrealist art, Edward James. In 2013, an Australian designer offered a red lobster mobile phone case, admitting that it was “a deterrent through its awkward and inoperative design, resulting in minimal enjoyment of function, zero fashion credibility and lastly, reduced mobility for the user.”

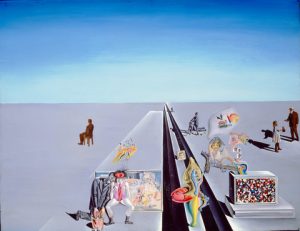

In The First Days of Spring, an ironically-titled canvas painted in 1929 before he joined the Surrealist movement, Dalí has Freudian symbols and details that he would develop later, and plenty of sexual graphics.

The curators highlight works they say illustrate a shared fascination with perspective: Dalí’s Christ of Saint John of the Cross from 1951, Apparition of Face and Fruit Dish on a Beach from 1938; and The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even (a later reconstruction by Richard Hamilton. Duchamp made this last composition an allegory of male and female desire and suffering, perhaps a function of his interest in what he called a “playful physics.”

The surprise element for the visitor is a reconstruction of Duchamp’s installation Twelve Hundred Coal Bags Suspended from the Ceiling over a Stove shown in Paris in 1938. This has been interpreted as comparing spectators to coalminers, tunnelling into the unconscious. By the late 1930s, France had seen much industrial unrest by the miners among others, and was facing political and industrial collapse.

Picture captions in detail:

Lobster Telephone (red), 1938. Salvador Dalí and Edward James. Photo: West Dean College, part of Edward James Foundation/© Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, DACS 2017.

Fountain, 1917. (replica 1964). By Marcel Duchamp. Rome, National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art. Photography: © Schiavinotto Giuseppe/© Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2017.

The King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes (verso with Paradise: Adam and Eve), 1912. Oil on canvas. By Marcel Duchamp. Philadelphia Museum of Art © Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2017.

The First Days of Spring, 1929. Oil and collage (paper, photograph, postcard, linoleum, transfer decal) on wood panel. By Salvador Dalí. Collection of the Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida. © Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, DACS 2017.

The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), 1915 (1965-6 and 1985). Oil, lead, dust and varnish on glass in metal frame. By Marcel Duchamp (reconstruction by Richard Hamilton), Tate: Presented by William N Copley through the American Federation of Arts 1975. Photo © Tate, London, 2017/© Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2017.

Dalí/Duchamp is in Galleries 1, 2 and the Weston Rooms, Royal Academy, until January 3, 2018. It will transfer to The Dalí Museum, St Petersburg, Florida, from February 5, 2018.