Human Rights in Japan: Freedom of Expression, the Media and the Constitutional Amendment

By James Brewer

Fundamental freedoms are at risk in Japan, the world’s third largest economy, a meeting in London heard.

Draft revisions to the constitution prepared by the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) would extend the powers of the government at a time when its attitude to human rights is already under sharp international criticism.

The concerns were graphically documented by a UK-based specialist on human rights and privacy, Dr Sanae Fujita, when she delivered a presentation on Human Rights in Japan: Freedom of Expression, the Media and the Constitutional Amendment

Dr Fujita told a meeting on April 26, 2018, of the Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation that reforms in the last few years initiated by the LDP had already damaged the framework of human rights and freedom of expression, including the independence of the media.

She drew attention to the latest development, the proposed constitutional reform. She highlighted worrying features which had received little coverage compared to that given to the most dramatic feature of the revamp – the supplementing of two war-renouncing clauses in constitution article 9 with a new clause justifying possession of national Self-Defence Forces.

Dr Fujita was concerned that a proposed amendment to article 21 on freedom of assembly and expression would add that “activities intended to harm the public interest and public order, and associations for such powers shall not be permitted.” She quoted David Kaye, United Nations special rapporteur on freedom of expression, as declaring: “Japan should be proud of article 21 in the present constitution, and not make any changes.”

Another disturbing point in the draft constitution was the potential removal of the word “absolutely” in the following: “The infliction of torture by any public officer and cruel punishments are absolutely forbidden.”

Further, two articles are to be added giving a prime minister power to ask the cabinet for permission to declare an emergency. Under that provision, the cabinet would be able to issue executive orders with the same effect as law, and “every person shall be subject to instructions of the state and other public organs.”

Dr Fujita went into considerable detail to posit that media independence was in question. She recalled that when she came to England as a student in 1999 to study international human rights law, she was shocked to see the media here. She compared the relative freedom in the UK to the failure, as she saw it, of the press in Japan to act as a public watchdog.

She alluded to the so-called “kisha” journalism clubs in Japan – cartel-like organisations including daily newspapers, television stations and agency services that provide easy access to information from the central and local governments and business associations. Freelances, the foreign press and Japanese magazines often criticise the “kisha” system, complaining it shuts them out of news conferences and briefings both on and off the record.

The many such press clubs nationwide are seen by critics as a way of spoon-feeding outlets with tightly-controlled information.

In the World Press Freedom Index 2018 compiled by Reporters without Borders, Japan is at a lowly 67th place, although this is a recovery from 72nd to which it slumped in 2015. The country had been as high as 22nd in the ranking in 2012. Reporters without Borders said that “Japan is a parliamentary monarchy that, in general, respects the principles of media pluralism. But journalists find it hard put to fully play their role as democracy’s watchdog because of the influence of tradition and business interests. Journalists have been complaining of a climate of mistrust toward them ever since Shinzo Abe became prime minister again in 2012.”

The campaigning body added that “on social networks, nationalist groups harass journalists who are critical of the government or cover ‘antipatriotic’ subjects such as the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster or the US military presence in Okinawa.”

In her extensive background analysis, Dr Fujita spoke of the public outcry and demonstrations over the special secrets bill enacted in December 2013, in a day of “regret and humiliation” for the Japanese people. Despite calls for amendments from the UN, and even though out of 90,480 comments, 60,579 were against it, the controversial legislation went into effect a year later.

That law, which was seen as prompting a decline in Japan’s standing as a protector of the free press,

had “a chilling effect on the media,” she said, in its failure to comply with international human rights standards on freedom of expression and the right to information.

Dr Fujita said that under the law, any information that was not convenient for Government could be deemed secret including information relating to nuclear plants such as Fukushima, which suffered a huge disaster in March 2011. The new law was criticised for its vagueness, severity, and lack of independent oversight. Others charged that the law was enacted without sufficient hearings or consultation with civil society and global experts.

In its condemnation of the proposal ahead of it passing into law, the UK human rights group Article 19 drew attention to its vague definition of what constitutes “protected information” and the potential imprisonment of whistle-blowers and journalists who release information. The group takes its name from Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights which states: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.”

Frank La Rue, UN special rapporteur on freedom of expression, was among those expressing concern that the legislation “not only appears to establish very broad and vague grounds for secrecy but also includes serious threats to whistle-blowers and even journalists reporting on secrets.”

It extended powers of a 2001 law allowing the minister of defence to withhold information “especially necessary to be made secret for Japan’s defence,” to other categories of information, including defence, counter-intelligence, diplomacy, “designated dangerous activities,” and prevention of terrorism. Every cabinet ministry and major government agency are similarly empowered. Public officials and private citizens who disclose classified information face prison terms of up to 10 years, while journalists who seek to obtain such details could get up to five years.

Opponents said that the law failed to meet global standards on national security and the right to information, called the Tshwane Principles, which were drafted by 22 organisations and academic centres from around the world, in consultation with more than 500 experts and endorsed by UN special rapporteurs.

Prime minister Abe insisted that a tougher secrecy law was needed to create a National Security Council based on the American model, and that normal reporting activity of journalists must not be subject to punishment.

Navi Pillay, the UN high commissioner for human rights, upset the government by accusing it of imposing the legislation without sufficient debate. She called for proper safeguards for access of information and freedom of expression as guaranteed in Japan’s constitution and international human rights law.

Mr Kaye, the UN special rapporteur on freedom of expression, had planned to visit Japan in December 2015 but Tokyo issued a snub by postponing the trip.

Eventually, Mr Kaye made an official visit to Japan in April 2016 but came in for a verbal “bashing” from pro-government, right-wing interests, and 46 professors accused him of unfair and biased views. His official report was submitted to the 35th UN Human Rights Council and found that although freedom of speech is strongly guaranteed in Japan, in practice there were serious threats to it and to the independence of the media.

In response, the Japanese government said his report was based on inaccurate information, claiming that it was only the individual opinion of one special rapporteur. Mr Kaye said that as article 21 of the Japanese constitution protects all forms of freedom of expression, this liberty must be protected for democracy and civil society to function.

The rapporteur said that the Japanese media lacked the benefit of organised solidarity among journalists, a concern that has been raised by many of them. This allowed their employers to exert pressure on their reporting, especially when critical of the government.

Mr Kaye’s report said that the Broadcast Act gives the government power to revoke the licence of a broadcaster it feels is politically biased. This policy chilled critical reporting of the government, as journalists self-censor their reporting under the shadow of the threat.

Dr Fujita assisted the official statements by the UN special rapporteurs to the Japanese government on the Bills on the Protection of Specially Designated Secrets of 2013 and the Anti-Conspiracy Bill of 2015, and supported the UN mission to Japan.

Dr Fujita spoke of the anti-conspiracy law which was approved in June 2017. This amended an existing law against organised crime syndicates by adding 277 new criminal charges of conspiracy and committing criminal acts.

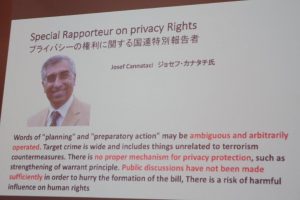

This sparked protests outside the parliament building, and Joseph Cannataci, the UN special rapporteur on the right to privacy, challenged the government over the contentious law. Mr Cannataci feared that public debate would be restricted, to the disadvantage of human rights.

The government argued the law was needed to improve security ahead of the 2020 Olympics, and to comply with a UN agreement Japan has signed. Critics said it weakens civil liberties and could be abused to monitor and target innocent citizens.

A further worrying episode was a statement in February 2016 by communications minister Sanae Takaichi that the government could suspend the operations of broadcasters if they repeatedly aired politically-biased programmes. In March 2018, Mr Abe sought to remove a political fairness clause in the Broadcasting Act as part of industry reforms.

Dr Fujita highlighted the so-called Moritomo scandal, one of the factors that has led to Mr Abe to his lowest opinion poll level since coming to office, with speculation that he may even step down during 2018. The scandal relates to a suspicious land sale in Osaka in 2016 involving allegations of favouritism and tampering with official documents.

Dr Fujita said that although a member of the Human Rights Council, Japan has not ratified optional protocols of any human rights treaties including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. As a result, Japan is the only developed country which has no access to any of the individual complaint mechanisms.”

Describing how tame the press could be, Dr Fujita cited as an example some of the Japanese coverage failing to show that when Ivanka Trump in November 2017 addressed a conference in Tokyo on women’s empowerment the hall was half-empty.

Dr Fujita referred to an April 2018 item on the BBC news site entitled #MeToo Japan: What happened when women broke their silence. The article said that in just a few weeks a spate of allegations had led to public figures being shamed and top officials resigning, but to a backlash against the women behind the claims. While denying allegations, Junichi Fukuda, the top bureaucrat in Japan’s finance ministry quit after being accused of sexually harassing a female journalist by making suggestive comments.

In the male-dominated media society of Japan, said Dr Fujita, women can be discouraged from speaking out. The BBC story quotes a lawyer as saying Japan’s law on sexual exploitation is way behind other countries.

At the same time, Dr Fujita was dismayed that media in other countries trivialised news from Japan – for instance a competition to celebrate baldness was featured in the British press at a time when Japan was going through serious political problems that needed to be debated internationally.

She said that in Japan only rich people could be candidates for parliament as a deposit equivalent to 46,000 euro was required to stand.

Originally from Osaka, Dr Fujita is an associate fellow of the Human Rights Centre, School of Law, Essex University. Since 2013, she has played an important role in raising international awareness of freedom of expression and information in Japan through links with UN special rapporteurs and other international experts. She teaches regularly in Japan on freedom of expression and the role of the media.

Journalist William Horsley, who chaired the Daiwa Foundation meeting, said that Japan for much of its history was under military dictatorship which curbed free speech. (Critics of the 2014 law have said it marked a return to the days when the state used the Peace Preservation Act to arrest and imprison political opponents).

There was too great a temptation for governments all over the world to make laws in their own interest, using control of the media to hang on to power in authoritarian ways, said Mr Horsley. In Japan, the system is very staid, less adventurous, and restricts media content. “My idea of journalism is that you pack in as much news from different sides as you can.”

Speaking on a day when the latest Reporters without Borders index on press freedom placed Britain in 40th place – it had been 22nd when the index was started in 2002 – Mr Horsley said that Japan was not uniquely at fault.

Mr Horsley is UK chairman of the Association of European Journalists and international director of the Centre for Freedom of the Media at Sheffield University. During more than 30 years with the BBC he was Tokyo bureau chief from 1983 to 1990 and later a BBC world affairs correspondent reporting on the reshaping of Europe’s political landscape following the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Jason James, Daiwa Foundation director, said the foundation was considering organising a discussion event assessing the impact on Japan of the #MeToo movement.