British Surrealism: strange dreams in the frame at Dulwich Picture Gallery

By James Brewer

“Delve deeply, fly faster, love to your heart’s content; what do your dreams reveal?” This is the invitation to a voyage through one of the 20th century’s most influential artistic styles as Dulwich Picture Gallery casts its net widely in its new exhibition British Surrealism.

In aid of a persuasive call to anyone who defines surrealism as merely “Salvador Dalí, René Magritte, Max Ernst and other giants from mainland Europe,” Dulwich sounds a roll call of UK artists, some of them long faded from prominence.

Some of the top artists took a draught briefly from the surrealist well before moving on, but many of those who featured throughout the fanciful, surrealist century will be unfamiliar names. They deserve to be brought back into the limelight. Whose interest could fail to be piqued by surprises such as one of the largest works in the show, with its curious title Abandonment of Madame Triple-Nipples and its raw impact?

Dulwich takes a somewhat romanticised view in defining surrealism, as did the founder of its modern incarnation, André Breton. The gallery prominently quotes Breton declaring in 1935: “Were one to consider their output only superficially, a goodly number of poets might well have passed for surrealists, beginning with Dante and Shakespeare at his best.”

This could hardly be disputed when one thinks of the strange characters on the island where the shipwrecked passengers wash ashore in The Tempest.

Getting to grips with the British angle on modern surrealism requires some background reading – the show catalogue written by the show’s independent curator David Boyd Haycock and fellow experts curator Sacha Llewellyn and archivist Kirstie Meehan, is a rewarding avenue for approaching the task.

In a selection of 70 works supported by archive material, the gallery tackles both the origins of surrealist art in Britain and elements which it says go back to 1620. In the 20th century, some Britons plunged directly into surrealism, while others were significantly haunted by it, disrupting established ways of looking at society and the intellect and emotions.

Here are 40 artists, with a scatter of their paintings, sculpture, photography, etchings and prints over three centuries. Creatures real and imagined and subverted architecture populate the visions, in a wild miscellany of experimentation.

The first thing we need to know is that this is the centenary of modern surrealism, for Breton began his experiments in surrealist writing in 1920, attracting a string of talented adherents but ejecting many from his circle.

According to Breton, the aim of surrealism was “to resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute reality, a super reality.” Thus, in their art and poetry the surrealists fed from the fantasy and freedom of dreaming. They were encouraged to delve into the concepts of automatic writing and free association, techniques that Breton took from Freudian psychoanalysis.

The subliminal mind and inner voices provided the canvas for transfiguring logic into bizarre scenes often with highly sophisticated draughtsmanship.

Britain played a big part in the inter-war prominence of the genre: London was chosen in 1936 to host the first international surrealist exhibition, which was formally opened by Breton and visited by 23,000 people. It was a platform for home-grown talent including Paul Nash, Eileen Agar (the only British woman participating), John Banting, Edward Burra, Merlyn Evans, David Gascoyne, Humphrey Jennings, Henry Moore and Julian Trevelyan. The main sensationalists there were the overseas contingent – Dalí delivered a lecture while wearing a deep-sea diving suit to represent plumbing the depths of the unconscious — while the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas proffered to visitors a cup of boiled string, asking them if they would like it “weak or strong?”

At Dulwich, one of the poster paintings is The Old Maids created in 1947 by Leonora Carrington (1917-2011) who was one of the last surviving surrealists from the 1930s. Leonora painted this strange tea party seen as a celebration of feminine creativity and power, in which interestingly the figure of the maid is taller than the women she is serving.

Carrington rejected the stereotypes in surrealism and the wider art world of women as subservient objects of desire, and drew on many sources: pagan stories of women with magic powers, Celtic literature, Renaissance painting, Central American folk art, medieval alchemy, and Jungian psychology.

The daughter of a Lancashire textile manufacturer, she had spent her childhood surrounded by animals and reading fairy tales, revisiting these memories in trauma after her partner, Max Ernst, was arrested by the Gestapo in France. She took refuge in the Mexican embassy in Lisbon before settling in Mexico. She was a champion of equality between the sexes and a founding member of the Women’s Liberation Movement in Mexico.

Another admirable woman surrealist was Marion Adnams, who was influenced by Dalí, Magritte and Nash and two of whose works stand out here. L’infante égarée (the Distraught Infanta) from 1944 shows a finely wrought paper figure modelled on Maurice Ravel’s composition Pavane pour une infante défunte which was dedicated to the arts patron Princesse de Polignac.

Two years later Adnams produced Aftermath, an oil painting alluding to the death and destruction of World War II. The setting of the of Dalí-esque composition is the English seaside, with the intrusion of an animal skull tied with a bow ribbon and of barbed wire. Adnams (1898-1995) lived and worked most of her life in her native Derby, learning from her drawing tutor, the surrealist painter Alfred Bladen.

Artist, poet and photographer Edith Rimmington (1902-1986) remained faithful to surrealism all her life. Here is her bold photomontage with gouache Family Tree from 1938 which is dominated by a double nautical chain stretching to the distance on a long pier. The motif might represent the strength of a loving family, but what of the wily snake coiling itself into the iron links – is this a reference to the serpentine politics of the time? The jetty is a sturdy construction above an ominous black sea, the ocean seen here perhaps in its capacity as the progenitor of humankind – the artist was closely interested in marine life – but storms were gathering in the year the work was created, and an eclipse (of values?) threatens.

Prize for the most intriguing title must go to Abandonment of Madame Triple-Nipples which is a pencil on paper sketch from 1939 by John Banting. Banting (1902-72) was a passionate anti-fascist. A year before he made this work, he was arrested when photographing Nazi troops marching into Innsbruck to enforce the incorporation of Austria into Germany.

The grotesque form and provocative title of The Abandonment is a gesture of savage social satire, an echo of his plunge into political life and his friendship with the rebellious Nancy Cunard (1896-1965) of the shipping family – her parents were Sir Bache Cunard, heir of the Cunard steamship line, and American heiress Maud Alice Burke. Nancy left privilege behind to become an activist and poet, organising relief missions for refugees from the Spanish civil war and fighting racism. Banting stayed with her in Harlem, New York, in 1932 and contributed to her Negro anthology of 1935.

Born in Chelsea, Banting at the age of 18 made drawings and wrote poems under the sway of vorticism, an earlier movement influenced by cubism and futurism. He went on to design for Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press and for two ballets at Sadler’s Wells.

Vorticism and surrealism were important in a highly practical way to Edward Wadsworth (1889-1949) although he was never formally associated with the latter stylistic genre. Towards the end of his service in World War I he was involved in the concept of applying camouflage designs to Royal Navy vessels which became known as Dazzle ships. The aim was to confuse enemy U-boats about the speed and direction of British ships. Wadsworth used nautical themes in his art for the rest of his career, including seascapes filled with oddly juxtaposed maritime-looking objects. Such was the case with his tempera painting on wood Satellitum in 1942.

Wadsworth was a member of Unit One, a grouping of modernist painters, sculptors and architects founded by Nash. In its brief existence from 1933 to 1935, the group helped establish London as a centre of modernist and abstract art and architecture.

Influenced by Wadsworth was John Bigge (1892–1973) who has a determinedly nautical work here, Composition, from 1936. Bigge wrote in the Unit One book that modern painting should avoid “sentimentality” and look for “Precision, clarity and simplicity.”

Bigge was a baronet – his full name was Sir John Amherst Selby-Bigge. After time in the forces in World War I (including serving as an inspector for the Macedonian mule corps in Greece, and later for the intelligence corps in Thessaloniki and Athens) he worked variously as a chicken farmer, in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford and as an estate agent. At the end of World War II, stationed with the British Red Cross in Austria, he was credited with saving the lives of anti-communist Slovenian civilians, managing to get rescinded an order to turn them over to the Tito regime which was torturing and executing returnees.

Bigge was captivated in the 1920s by an exhibition in London of the Italian artist Giorgio de Chirico (who was born in Volos, Greece), who founded the dream-like style known as metaphysical art. In the catalogue for a 2014 exhibition at Abbot Hall Art Gallery the collector Jeffrey Sherwin wrote of Bigge that “his landscapes and seascapes are considered among the most effective of any artist associated with the British Surrealist movement.”

The tortured and vicious politics of the 1930s had a huge impact on many of the artists, and among them women produced some of the most daring works, firmly rejecting their assigned roles in art as muse or femme fatale.

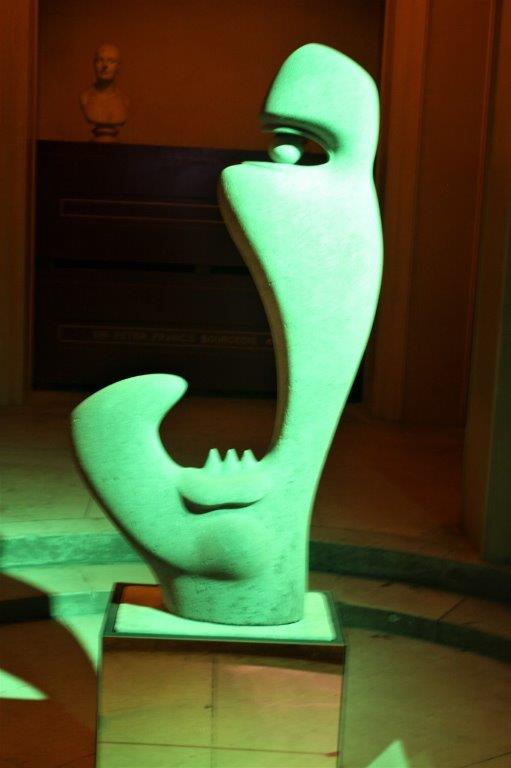

Brightly illuminated in a central alcove at the Dulwich gallery is the sculpture Spanish Head by FE McWilliam, made in 1938-9 from Hopton Wood Stone, which is quarried in Derbyshire. The influence of Picasso’s enormous painting Guernica of the agony of the bombing of the Basque town was profound upon sculptors including Henry Moore and on painters. In the McWilliams piece, the features are reduced to a single piercing eye and it is as though a scream from behind the bared teeth pierces the atmosphere. A contemporary and friend of Moore, Frederick Edward McWilliam (1909-92) was born in County Down. He made his name in London and established a reputation as one of the most important sculptors of his generation. Although the Spanish Head looks robust, we are warned by the gallery that it is fragile to the touch.

Inspired by artists such as Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí and Man Ray, Conroy Maddox rejected academic painting in favour of outrageous techniques such as the “ready-made.” Maddox’s Onanistic Typewriter (1940) is a typewriter with its keys upended into spikes. Maddox remained a committed surrealist for more than 70 years,

In his First Manifesto of Surrealism, Breton named 25 poets, novelists and playwrights from the 17th to the 19th centuries who he said inspired the movement, including William Blake, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Henry Fuseli, Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear.

In the current exhibition, Blake is hailed as “an ancestor par excellence of surrealism.” In 1803 he wrote the famed lines: “To see a World in a Grain of Sand/ And a Heaven in a Wild Flower/ Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand/ And Eternity in an hour/ A Robin Red breast in a Cage/ Puts all Heaven in a Rage…” and in Jerusalem he sought “to open the Eternal Worlds, to open the immortal Eyes of Man inwards into the Worlds of Thought, into Eternity ever expanding in the Bosom of God, the Human Imagination.”

Literary treasures here include a notebook with Coleridge’s 1806 draft of The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and a play script for Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1859).

Two of the most striking works are in the first room which majors on the realm of dreams: Heaviness of Sleep (1938) – depicting a mystic landscape that is both arid and fertile – by John Armstrong (1893–1973) and Burra’s macabre Dancing Skeletons (1934).

The final room explores the irrational, the impossible and the absurd, with highlights including works of nonsense and fantasy by Carroll, Francis Bacon’s contrarian Figures in a Garden which is a rare surviving work from early in his career in 1935; and from 1783 Fuseli’s scary Macbeth.

Curator Dr Boyd Haycock said: “Surrealism was probably the most exciting, transgressive and bizarre art movement of the 20th century. Its impact on a wide range of British artists, including a number of radical female artists, was enormous.”

Jennifer Scott, the Sackler Director of Dulwich Picture Gallery, said: “If you thought surrealism was solely born in France, think again! There is often something absurd and imaginative within British creativity, from Shakespeare to Lewis Carroll to Henry Moore.”

In one of its wall labels, Dulwich offers have-a-go encouragement to visitors: ““Scribble, riddle and rhyme. Let yourself go. You never know what you might find. Surrealism is a door open to everyone.”

Picture captions in detail:

Composition. 1936. By John Bigge. Photo: Ferens Art Gallery: Hull Museums, © The Estate of John Bigge.

Abandonment of Madame Triple-Nipples. Pencil on paper. 1939. By John Banting. Private collection. Anthony Wharton.

Satellitum. Tempera on wood. 1942. By Edward Wadsworth. Nottingham City Museum and Galleries.

Spanish Head. By FE McWilliam. © The Sherwin Collection / Estate of FE McWilliam.

L’infante égarée. 1944. By Marion Adnams, Photo: Manchester Art Gallery/Bridgeman Images.

The Old Maids. 1947. By Leonora Carrington. © Estate of Leonora Carrington/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019, UEA 27. Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, University of East Anglia. Photographer: James Austin.

Family Tree. 1938. By Edith Rimmington. The Murray Family Collection (UK & USA) © Estate of Edith Rimmington.

Aftermath. 1946. By Marion Adnams. Photo: 2006 Christie’s Images Ltd, © The Estate of Marion Adnams.

Onanistic Typewriter I. 1940. By Conroy Maddox, Photo credit: The Murray Family Collection (UK & USA). Given with the kind permission of the artist’s daughter.

British Surrealism is at Dulwich Picture Gallery until May 17, 2020.