By James Brewer

An engrossing masterclass in one of the predominant artistic trends of the 20th century is dazzling spectators at London’s Whitechapel Gallery. Epic canvas after epic canvas tells the story of how women artists helped shape Abstract Expressionism, the individualistic genre that burst onto the scene as a reaction to, and offshoot of, the collective memory of the second world war.

The exhibition Action, Gesture, Paint: Women Artists and Global Abstraction 1940-70 opens with Helen Frankenthaler’s 1974 grand-scale painting April Mood, one of the best representations of artistic exploration of the variable physical characteristics of paint, abandoning many of the accepted conventions around structure and composition. April Mood is a striking example of the 1970s Colour Field canvases of Frankenthaler (1928-2011). Despite its abstract nature, its aura of spontaneity in which saturated hues float like drifting clouds in an exuberant spring landscape, lifts the spirits of the viewer. Its sense of poignancy and elation confounds the notion that Abstract Expressionism is a forlorn niche that lacks power to connect with the emotions. In fact, the many canvases and the backstory of their creators, as carefully collated by this exhibition’s curators, speak to the global weight of what was a simultaneous out-pouring of anxieties of the age. What emerges is art that while abstract is also expressive and indeed could be seen as poetic, inspiring a different way of looking.

The four-metre-long acrylic canvas April Mood is a manifestation of why Frankenthaler is a major figure in the movement, if such a scattered and splattered story can be thus called. In New York in 1952, she evolved a signature form of abstraction achieved by working on the floor, diluting her paint, and allowing it to soak into the fibres of a canvas. This achieved a rich yet luminous watercolour effect and billowing forms. She described the resulting body of work as ‘drawing with colour’ and made increasingly monumental paintings that influenced generations of artists.

For this expansive show, the gallery has brought together more than 150 paintings and drawings wrought by what it describes as an overlooked generation of 80 international women artists, and insightfully tells their story. While every canvas is devoid of human figuration, each seizes the viewer’s attention with its forceful vitality.

Throughout, the paintings are bold and, assembled as the Whitechapel has done, are a cataclysmic expansion of the narrative to date of Abstract Expressionism, in which the spotlight has been chiefly on white, male painters. This puts on record that numerous women artists (a few hiding behind masculine pseudonyms) were in the forefront of picking up their paintbrushes and palette knives to dash and sometimes slash their marks in what became known as gestural abstraction.

It is stressed that this field of art arose as geopolitical conflict, civil war and unrest flared in nations large and small. Propelled by creators mostly based in New York City, it became known as the New York school. The name reflects an endeavour to create non-European styles of painting, and some proponents were inspired by the surrealist concept that art should come from the unconscious mind as suggested by the Catalan artist Joan Miró, who once said: “I try to apply colours like words that shape poems, like notes that shape music.” Even though some practitioners took up the idea that they should “let the paintbrush do the work” there was no sapping of energy in the search for new expressive forms in an investigation of the nature of existence. In the US, led by Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, so-called action painters often used large brushes or paint dripped from brushes or pots to splurge their marks on canvases sometimes placed on the ground.

The exhibition disentangles some misconceptions – it underlines that, while New York catalysed Abstract Expressionism, artists all over the world mid-century were exploring similar themes, ranging in Europe from Art Informel (which turned its back on classical artistic principles) to Arte Povera (Italian artists using cheap, commonplace materials); in East Asia with calligraphic abstraction; and in Central and South America and the Middle East with experimental, highly political stances.

Some of the American women associated with Abstract Expressionism, including Helen Frankenthaler and Lee Krasner (1908-1984) did become widely known, but they were exceptions. April Mood came after momentous changes in Frankenthaler’s life, including her divorce from another leading Abstract Expressionist, Robert Motherwell, and a wave of professional success including a retrospective at the Whitney Museum in New York. The eminent art critic and historian Barbara Rose wrote: “Her paintings are not merely beautiful. They are statements of great intensity and significance about what it is to stay alive, to face crisis and survive, to accept maturity with grace and even joy.”

Lee Krasner had a fruitful inclination for themes of mythology and symbolism. Her work Bald Eagle (1955) has returned on loan to Whitechapel Gallery for the first time since a retrospective in 1965. It typically enlists organic elements in autumnal colours. She was an established artist with a distinctive style when she married Jackson Pollock – she is at least as interesting as her husband for her role in abstract expressionism – and worked with him on collage images which included torn fragments of paintings by both artists which she let fall to the canvas. Their marriage was failing but mourned his death in a car accident in 1956, taking over his barn studio as her work grew in scale and ambition. This was the background to her turn to what became known as her Umber Paintings, with an earthy palette of umber, cream and white, the repeated marks suggesting foliage, swirling wind, feathers, and wings. Shown here alongside Bald Eagle is Feathering, from 1959, an example of painting at night under artificial light amid her insomnia.

Audrey Flack, born 1931, is another strongly individual US artist. While a student at art school she became a member of the influential 8th Street Club – opened in 1949 at 39 East 8th Street, Greenwich Village as a social centre by a group of Abstract Expressionists and a short distance from another artists’ haunt, the Cedar Tavern. A proposed club rule that women be barred was soon dropped. Audrey Flack produced works that were structurally ordered yet gestural and fluid, often naming them after artists she admired.For instance, Abstract Force: Homage to Franz Kline, painted in oil in 1951-52 is a tribute to Franz Kline (1910-1962) who made abstract, monochromatic paintings using domestic paint brushes following his earlier compositions in colour. Later in her career she became a pioneer of photorealism. She has said: “Artists do not just paint for themselves, and they don’t simply paint for an audience. They paint because they have to.”

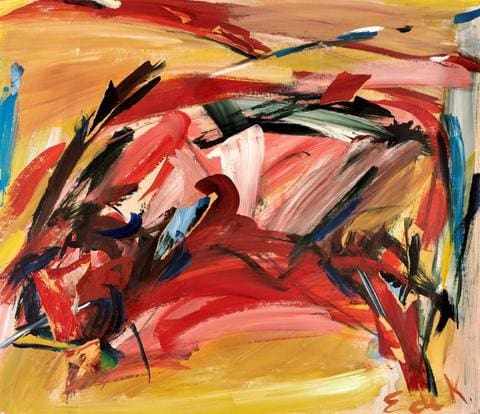

Another fixture in the New York School of the 1940s and 50s, Elaine de Kooning (1918-1989) chose to sign her artworks EDK to avoid her paintings “being labelled as feminine in a traditionally masculine movement” and to distinguish them from those of her husband, Willem de Kooning. Willem employed a frantic style disciplined by geometric planes, while Elaine brought Abstract Expressionism to bear on figurative subjects such as bullfights and portraits of friends and family. Among her works on show here is The Bull from 1959 in acrylic and collage on Masonite.

More than half of the works at the Whitechapel have never been on public display in the UK. These include untitled pieces from the 1960s by South Korean artist Wook-kyung Choi (1940-1985). These evoke dissonance but tactility, with white and blue stripes juxtaposed against acrylic patches in intense greens, yellow, orange and red. Influenced by Korean Art Informal and by Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art in the US, her paintings are constituted with rapid and seemingly chaotic brushwork, alongside passages of more controlled application. She moved from South Korea to the US in the early 1960s and had a short but prolific career before her early death.

Gestural abstraction emerged in South America as part of popular defiance of dictatorial regimes. Notable in the protest movement is Marta Minujín (born in 1943 in Buenos Aires), a pioneer of happenings, performance art, soft sculpture, and video, making work that is monumental yet fragile. In the examples on show, two untitled works from 1961, she worked on the floor using sand, lacquer, chalk, and carpenter’s glue to form highly textured surfaces, and coated them with thick layers of paint.

In her long artistic career in Argentina, the US and Europe, Marta Minujín has used surprise, provocation, and even violence. Once she destroyed all her sculptures that had been exhibited just a few days earlier in her studio – symbolising a protest against the transformation of art into a consumer product and attempting to demystify art as an object. She went to New York in 1966 on a Guggenheim Fellowship, readily engaging with the avant-garde there and collaborating with artists including Salvador Dalí and Andy Warhol.

One wonders if the title of one of the oil paintings of Asma Fayoumi (born in Jordan in 1943) was a premonition of the destruction unleashed by the earthquakes of February 6, 2023. Requiem for a City is dominated by fragmented blocks of deep red, that hint at architecture tumbling among sharp slivers – one of them reminiscent of a dagger – that might easily signal cries of anguish.

In fact, Requiem for a City was painted in 1968 and being inspired by traditions of city of elegy and later by city elegy as in the prelude to odes addressing the ruins of abandoned encampments. Fayoumi’s rendering aligns with the profound way artists have drawn on the region’s rich cultural heritage translating them to international modes of abstraction. She was a key figure in 1960s Syrian Abstraction which emerged against a background of social change, opposition to Western influence and the search for new artistic identity. After initially painting cityscapes, she moved to more abstract forms and gestural expressionism. Her later works featured female figures drawn from mythology.

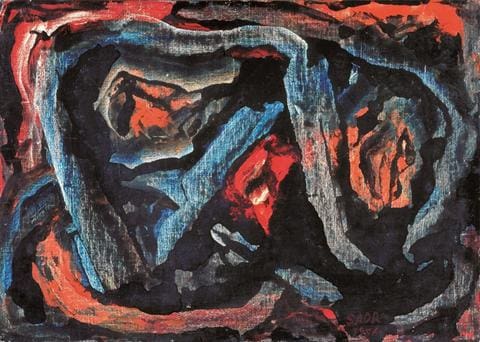

Painted in 1956, an intimate untitled work by Iranian artist Behjat Sadr (1924-2009) recalls her preoccupation with the colour black. From a dark background emerges an interplay of oppositional reds and blues in thick, layered strokes, of the kind she sometimes made with a palette knife or with her hand. The year was critical to her career, for it was when she exhibited in the Italian pavilion at the Venice Biennale, being one of the first women on the international biennale scene. She had gone to Italy four years earlier on a grant from the Italian government, continuing her art studies in Rome, and graduating from Naples Fine Arts School. Sensitive to political movements of emancipation and insurrection, she experimented with kinetic shapes and Op art.

Early in her stay in Rome, Behjat Sadr met the inspiring Forough Farrokhzad, a woman who was to earn a reputation as a leading Iranian poet. In Italy she developed a style of non-geometrical abstraction, ceasing to paint on an easel, saying: “I was entering an unconscious trance, applying paint pots and scrapers to my large canvas laid out on the floor.” She moved to Paris in 1980 after the Islamic revolution in Iran, and the Iran-Iraq war and her illness persuaded her to stay in France. She loved swimming in the sea and in 1991, wrote in her notes: “I like the sea more than the earth. In the earth, one ends up buried. At sea, one is immersed, as one is immersed in joy, in beauty, in happiness, in delirium, in work. . .The earth has mountains, hills, crevices, while the sea is endless, driving the eyes towards infinity.”

Gillian Ayres (1930–2018) was a leading exponent of the radical developments in abstract painting dominating British art in the 1950s and 1960s. Her heavily worked canvases reflected how she said she saw the world, in ebullient shapes and colours. She was among those who made early work by pouring paint directly onto the canvas. Her oil painting Break-off, featured here, marks a time when she reverted to using a brush, producing a greater sense of order and structure. London-born Ayres studied at Camberwell School of Art and exhibited with the Young Contemporaries in 1949.

We are introduced to lesser-known figures such as Mozambican-Italian artist Bertina Lopes (1924-2012) whose gestural work responds to Mozambican iconography and her growing anti-fascist and anti-colonialist views. On display are two works from 1969 made after she fled Mozambique for Portugal and later Rome.

Another often unsung heroine is Ukrainian-born artist Janet Sobel (1893-1968) who may have informed Jackson Pollock’s approach to dripped compositions – Pollock said that her method impressed him. Janet Sobel was a mother of five and a grandmother when she took up painting in her apartment in 1939. The curators say that she appears to transfer pure emotion directly onto the canvas in for instance The Illusion of Solidity (c 1945), where clouds of reds, yellows, greens and blues conflict with an evolving mass of pink and black swirls scored into the paint.

Toko Shinoda (1913-2021) is said to have become the first prominent woman artist in Japan and was among the few Asian artists to be associated with Abstract Expressionism. On display are prints which demonstrate how, with rhythmic lines and gestures, she crossed the boundaries between East Asian calligraphy and Western-style modern art, and in doing so invented her own field.

Shown in the UK for the first time are two bold abstract compositions exploring nature and place, made in 1967 by Lea Nikel (1918-2005). She was born in Ukraine and moved to Israel, where she lived and worked for most of her life, developing a distinctive style of gestural abstraction.

Laura Smith, Whitechapel Gallery curator said: “Action, Gesture, Paint reveals how these international artists were redefining artistic practice as an immersive arena for action, process and consciousness, drawing on the avant-garde movements of Expressionism and Surrealism. We also see how they endowed the ideas and methodologies of the movement with their own specific cultural, political and subjective dimensions. Their paintings were regarded not as images but as events, and they were an important catalyst for changing ideas around aesthetics, poetry, philosophy, and politics in their distinct and particular regions.”

Many of the works are loaned by the British art collector Christian Levett, a former hedge fund manager now living in Florence, who developed his passion for art when working in Paris at the age of 25. During the Covid lockdown he started to collect female works of Abstract Expressionism for his home by the Arno River, conscious that women have “taken a back seat in art history.”

At Mougins Museum of Classical Art which he founded in the south of France and named after the village where he has a holiday home, he has amassed some 2,300 artworks. Opened to the public in June 2011, the collection houses thousands of Greek, Roman, and Egyptian artefacts and contemporary items, and loans them to other museums and universities. Mr Levett says that his idea is not to sell his artworks, but to leave them in heritage to his children and grandchildren.

A curatorial advisory board for the exhibition comprised Iwona Blazwick, Margaux Bonopera, Bice Curiger, Christian Levett, Erin Li, Julia Marchand, Joan Marter, Laura Rehme, Agustin Perez Rubio, Elizabeth Smith, Laura Smith, Candy Stobbs and Christina Vegh. After London, the show will travel to France and Germany: Fondation Vincent Van Gogh, Arles, from June 3 to October 22, 2023, and Kunsthalle Bielefeld, from December 2, 2023, to March 3, 2024.

The exhibition is supported by the Terra Foundation for American Art, with additional support from the Christian Levett Collection, Be Flâneur, Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Soo & Jonathan Hitchin, Galeria Nara Roesler and Richard Saltoun Gallery. Further thanks go to Atelier Ellis and Embassy of Italy in London.

Captions:

Abstract Force: Homage to Franz Kline, 1951-52. By Audrey Flack. Oil on canvas. The Christian Levett Collection.

April Mood, 1974. By Helen Frankenthaler. Acrylic on canvas. Helen Frankenthaler Foundation.

Two paintings by Lee Krasner. Bald Eagle, 1955. Oil, paper, and canvas collage on linen. Pollock-Krasner Foundation; and Feathering, 1959. Oil on canvas.

Requiem for a City, 1968. Oil on canvas. By Asma Fayoumi. Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah.

Untitled, 1956. Oil on wood. By Behjat Sadr. Courtesy of Behjat Sadr Estate © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2022.

Untitled, 1961-62. Detail. Sand, pyroxylin shellac, chalk, and carpenter’s glue on hardboard. By Marta Minjuin. Courtesy of the artist, Henrique Faria, New York & Herlitzka+Faria, Buenos Aires.

Two untitled works, 1960s. Acrylic on canvas. By Wook-kyung Choi. © Wook-kyung Choi Estate and courtesy to Arte Collectum.

Break-Off. Oil on canvas. By Gillian Ayres. Tate. Purchased 1973.

The Bull, 1959. Acrylic and collage on Masonite. By Elaine de Kooning. Courtesy the Christian Levett Collection © EdeK Trust.

Action, Gesture, Paint: Women Artists and Global Abstraction 1940-70 is at the Whitechapel Gallery until May 7, 2023.