City of London at War 1939–45. New book tells of courage amid carnage in the Square Mile

By James Brewer

Here is a story that could hardly be more appropriate for citizens under siege – it is a saga of an existential struggle. A new book, City of London at War 1939–45, has a title to make us shudder at how the core of the great metropolis withstood relentless battering by an enemy; the menace then was starkly visible, in the shape of bombers unleashing firestorms from the skies.

This reminder of what Britain and many other countries went through in savage conflict comes as national leaders in the current desperate times evoke the wartime spirit.

War in Europe raged for a day short of six years. The coronavirus emergency – the fight against a sinister and unseen foe – will surely last for nowhere as long, although its after-effects will be felt by men, women and children and our societies for years after the eventual conquest.

Packed with detail, the 169-page book comes from Stephen Wynn, who since retiring from long service as a police constable in Essex has specialised in recording the history of English cities and towns in the first and second global wars.

In World War II, the City of London did its best to carry on as normal – in contrast to the “stay at home” instructions that have characterised the spring 2020 offensive aimed at curbing the spread of pandemic.

The capital including its business district came under ferocious bombardment – it was targeted on 79 occasions during the war and at one stage the Luftwaffe carried out raids on 57 consecutive nights.

On the first evening of the Blitz, an onslaught which lasted between September 7, 1940 and May 21, 1941, some 350 bombers escorted by 600 fighter aircraft killed 450 civilians and seriously injured 1,300. On December 29, 1940, incendiary and explosive bombs caused a firestorm so intense it was called the Second Great Fire of London.

In all in the Blitz, some 6,000 people died in London and 12,000 were injured. Nationally, 43,000 civilians perished.

That was just a start. The worst raid on the City was on December 29, 1941 when Hitler’s air force dropped hundreds of incendiary devices on historic edifices and on homes in the capital. Buildings crumbled as teams of courageous firefighters did their best to tackle the inferno. Some of the structures had to be blown up to prevent the conflagration spreading. From mobile canteens, members of the Women’s Voluntary Service served cups of tea to the exhausted brigades and to frightened civilians.

The Guildhall, home to the City corporation, was on fire, with a Union Jack fluttering from the front of the building like an act of defiance, as was the criminal court, the Old Bailey. St Paul’s Cathedral was endangered, but cathedral staff bravely put out incendiary bombs that fell on the roof, and neighbouring fires were kept at bay just in time. Cannon Street, Cheapside and Moorgate were among areas shattered.

Amid this devastation, a remarkable human story emerges. Stephen Wynn concentrates on chronicling the City in terms of the effect on the population – the number of residents was small, but thousands commuted into the Square Mile to work.

The author chooses this tack rather than relating the fate of the business sectors, such as shipping, insurance and the legal profession, some members of which decamped for the duration. That would have been too much for the compass of a modest-sized book. Many institutions kept going: the London Stock Exchange was closed for only a few days because of bomb damage.

Grand occasions continued doggedly at the Guildhall and Mansion House (where Churchill gave many of his speeches), possibly to convey the message that the City was capable of functioning as normal. Princess Elizabeth, later to be Queen, in May 1944 paid her first official visit alone to the City, to preside over the diamond jubilee meeting of the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children.

The princess had already committed to an auxiliary role. Despite the misgivings of her parents, Elizabeth Windsor joined the Women’s Auxiliary Territorial Service as a second subaltern and trained in the capital as a mechanic and military truck driver. It was hardly surprising that her address to the nation on April 5, 2020 seeking to foster unity in the pandemic crisis revived what she saw as the spirit of World War II, and she recalled her first radio broadcast, with her sister Margaret in 1940. At the end of the war, the sisters crept out of Buckingham Palace to join crowds celebrating in London.

In the face of day and night assaults aimed at spreading fear and panic, says the author, “British morale never wavered, well maybe a little bit, but it certainly did not have the desired effect of demoralising Britain into surrendering.”

Movingly, Mr Wynn lists the names and backgrounds of many of those killed in the rain of incendiary bombs on January 11, 1941, some of the victims happening to be near Bank underground station. Similarly, he details casualties at Liverpool Street railway station and near St Paul’s tube station, in Bishopsgate and Cannon Street. He has researched the backgrounds of many of those who perished and whose names are listed on monuments that can be seen in the City. This will for many readers recall the three Tower Hill memorials that are technically beyond the City bounds: the Mercantile Marine War Memorial unveiled in 1928; the Merchant Seamen’s Memorial unveiled in 1955 marking the heavy losses of ships and their manpower; and the commemorative tribute to merchant sailors killed in the 1982 Falklands War.

The City was always going to be a target for German bombers: it had no industrial plants or docklands, but it was proud of its ancient architecture and had plenty of intangible assets – a workforce of all the talents and the resolve of the wealthy and the poor alike to stand firm – that the Nazis sought to target. Elsewhere in London, especially the East End, the docks were pounded mercilessly.

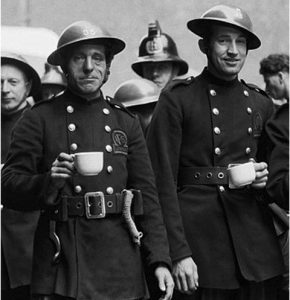

Many of the 50 illustrations in the book offer a glimpse of the heroism and fortitude of the population, including the resolute contribution of women.

Mr Wynn examples the bravery of staff at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, one of the medical facilities that remained open during the war. The hospital was quickly put to the test. On November 18, 1939, it had to take in and treat 107 survivors of the Dutch passenger ship Simon Bolivar which was blown up and rapidly sank after striking a German mine in the North Sea. The steamship had left Amsterdam with more than 400 passengers and crew, most of them British, Dutch and Norwegian and with some German refugees. A day after medically treating them, Bart’s released 91 people. Carrying over their shoulders paper bags containing their remaining possessions, they were taken to hotels. Five of the women had babies in arms and another five had young children with them.

The roles of volunteers, including the Home Guard which in the City comprised 25 battalions, and the Fire Watchers, are covered. There was extensive recruitment: many regiments, comprised of volunteers, members of the Territorial Army and regular soldiers, had connections with the City. The Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) lost 1,765 officers and men of whom 1,039 died fighting in Italy.

At first the government refused to allow people to shelter in the London Underground because they wanted to keep the lines free for commuters and troop movements. After two weeks of the Blitz and protests from civilians, ministers changed their minds and opened the gates. Soon, 150,000 people were sleeping in a total of 79 subterranean stations each night. Some people bedded down on the platforms, others between the tracks., amid dust, rats and the snoring of fellow Londoners.

At the outbreak of war one of the two MPs for the City of London was Sir Alan Anderson, whose father in 1878 had amalgamated the family shipping business of Anderson, Anderson & Co with Frederick Green & Co into the Orient Steam Navigation Co (which in 1966 became part of P&O). Anderson started in the family shipping business before becoming a director of the Midland Railway, and in World War I helped regulate the distribution of wheat supplies. In 1917 he oversaw the construction and repair of both Royal Navy and merchant vessels. He retired as an MP in 1940 but the following year was appointed controller of railways.

Despite the damage to its infrastructure and the suffering of its population, by the end of the war the City of London was ready to rise again, and to augment its role as an international financial capital. What had also risen again was a mountain of national debt, as had been the result of fighting the first world war, a sum that was still enormous on the eve of the second. Food rationing, which began in the UK in January 1940, ended fully only in 1954.

Stephen Wynn is conscious of the fortunes and misfortunes of war. His two sons served five tours in Afghanistan between 2008 and 2013 and both were injured. This led to the publication of his first book, Two Sons in a Warzone – Afghanistan: The True Story of a Father’s Conflict, published in October 2010. Both his grandfathers served in and survived the first world war, one with the Royal Irish Rifles, the other in the merchant marine, and his father was a member of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps during the Second World War.

City of London at War 1939–45 (paperback) by Stephen Wynn, is published by Pen & Sword Military in the series Your Towns & Cities in World War Two. ISBN: 9781526708304.