In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900–1930s. An epic exhibition at the Royal Academy, London

By James Brewer

She was a brilliant artist who helped revolutionise theatrical set and costume design in Ukraine and Russia, and well beyond. A hundred years ago, Alexandra Exter created daring and flamboyant stage wear, including applying body paint instead of clothing, paving the way for countless fashion trends.

One of a swathe of talented and pioneering Ukrainian artists many of whose names were to be blotted out of history or “forgotten,” Alexandra and her contemporaries were a huge influence on modernist art in Europe, and ultimately in the US.

She and others are given her due in an outstanding exhibition that has just arrived at London’s Royal Academy: In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900–1930s.

Alexandra was among a cohort that linked the flowering of modernism in Ukraine, the Cubists of Paris, the Futurists of Italy, and radical art movements of Russia. She moved in a crowd of figures such as Picasso, Braque, and Léger, all cutting loose from traditional creative forms. It was an era when the Ballet Russes were sending shock waves through stage, design and music.

The Royal Academy has mounted this exhibition at a time when Ukraine and its very existence are under a global spotlight. Once again, Ukraine is “in the eye of the storm.”

The appellation itself of Ukraine presents a puzzle. It is uncertain how the country’s name came about. It has been traced to a word translated as “at the edge,” and has been viewed thus geopolitically by among others the occupants of the Kremlin. A growing body of opinion prefers the translation of the term as “a country or a region.”

This latter sense suited the essence and spirit of the country in the early 1900s because artists there were far from being “on the edge” of breakthroughs in artistic vision. They were central to European achievement. The complex historical background resulted in a vibrant mix of Ukrainian, Polish, Russian and Jewish elements that created a distinct cultural profile. Ukraine had for centuries indeed been a borderland, with its territory divided between empires and its people perceived as a single nation only from the late 19th century. Short periods of independence were propitious to asserting a Ukrainian identity.

The exhibition relates how when the Ukrainian entity was divided between the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires, its cities were not even allowed their own art academies. Aspiring artists had to move elsewhere to complete their studies and find a more welcoming milieu, but this proved a boon. They initially gravitated to the Imperial Academy in St Petersburg, but increasing numbers moved to Munich and Paris, experimenting with the new visual languages they found there such as Cubism, geometrical concepts, fragmentation of the picture plane, and Futurism with its impassioned energy. Amid war and revolution, they advanced towards abstraction, sometimes coupled with the vivid colour and rhythmic impetus of Ukrainian folk and decorative art. Vigorous new groundwork was constantly essayed in art, literature, theatre and cinema.

Highlighting the rich range of artistic styles, the new exhibition proceeds crisply through thematic sections. Interspersed are brief captions with snatches of the story, little known in West Europe, that unfolded.

In chronological order, the show unfolds a jagged trajectory. There are neo-Byzantine paintings by the followers of Mykhailo Boichuk and experimental works by members of the Kultur Lige (the Jewish Culture League), who sought to promote contemporary Ukrainian and Yiddish art, and fanciful stage designs. The names of some who were born and started their careers in Ukraine gained international renown, among them Alexandra Exter, Wladimir Baranoff-Rossiné, Sonia Delaunay, Kazymyr Malevych and El Lissitzky. The mostly male participants egged on one another to more and more radical practices, as seen in the show’s 65 works, many of which are on loan from the National Art Museum of Ukraine and the Museum of Theatre, Music and Cinema of Ukraine.

The exhibition explores theatre design as one of the most vigorous expressions of modernism by Ukrainians, highlighting work by Exter, Vadym Meller (who triumphed in Ukraine, Paris and New York) and Anatol Petrytskyi (a designer in opera, ballet and drama in Kharkiv, Kyiv, and Odessa. He also designed sets for performances in the Moscow Bolshoi and Malyi theatres). Exter’s friend Les Kurbas, later executed after being framed up by the state, shaped the distinct character of theatre in Ukraine. The censure of theatre has resonance in the current brutal war: in the decade since the Maidan demonstrations which led to the country shrugging off links with Russia, Ukrainian playwrights and producers have flourished – but Russia has stood accused of shelling Mariupol’s theatre, causing the death of 300 people who had been sheltering there.

Alexandra Exter (1882–1949) lived in Kyiv for more than 35 years. She worked with ballet dancer and choreographer Bronislava Nijinska’s School of Movement and was a co-curator and designer of the folk-art exhibition at the National Art Museum in 1906. With Mykhailo Boichuk she led the charge of new ideas into Ukraine and was the first to publish a detailed analysis in Russian of Cubism. She moved to Paris in her twenties, returned to Ukraine, and later lived in Russia before returning permanently to France. She inspired much of the Art Deco movement in the 1920s and 30s, and devised scenography for many plays, worked in fashion and created textiles and interiors. In 1925 came those ‘epidermic’ ballet costumes, using body paint instead of clothing. Just ahead of that were her ‘Martian’ costumes and set designs for Aelita: Queen of Mars, a 1924 science-fiction film. Those costumes were made from acrylic, aluminium, glass, celluloid, and sheet metal.

Through peasant workshops she united folk art with the avant-garde. In the traditional needlework of Ukrainian countrywomen, Alexandra saw designs echoing the abstractions of the studio modernists. She employed embroiderers to turn designs by the Kyiv-born Kazymyr Malevych into rugs, scarves and pillows. On display in London is Alexandra Exter’s oil on canvas, Three Female Figures, from 1909-10. From 1924, she settled in Paris – just as well, as among other reasons it meant she could not be reached by the Stalinist purges that began in the 1930s.

The art section of the Kultur Lige had brought together young artists such as El Lissitzky to stimulate a blend of the Jewish art tradition and the European avant-garde. The league was founded in Kyiv in 1918, in the face of antisemitism and the horror of pogroms. Marko Epshtein (1899-1949) was prominent in the league, producing book illustrations, and started the Museum of Jewish Art, housing paintings by Marc Chagall and others.

In surviving prints by Epshtein we see him rejoicing in dynamic line and a charming element of whimsy. The Tailor’s Family, Woman with Buckets (The Dairy Maid) and Cellist dating from around 1920 are worked from basic materials — Indian ink and watercolour on paper pasted on cardboard. Epshtein escaped the Ukraine repression, moving to Moscow. By the mid-1920s, the Kultur Lige was shut down under pressure from the Soviet regime.

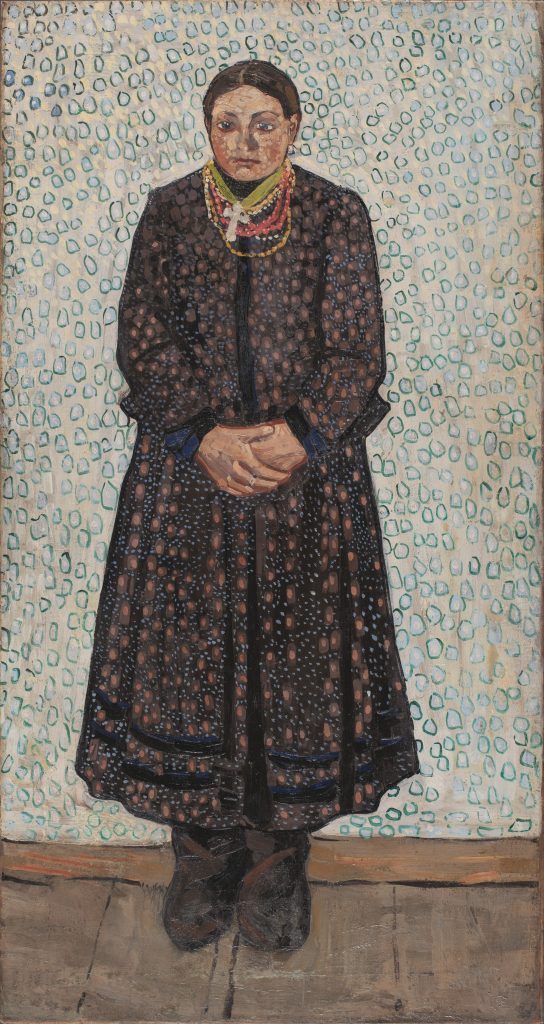

Like Exter, Mykhailo Boichuk (1882-1937) who gave his name to a Ukrainian school of monumental art and frescoes, brought ideas from the West, in his case inspired by Giotto and Cimabue and by Byzantine iconography. He esteemed the working women he pictured as did his brother, Tymofii (1896-1922). The latter recorded scenes from rural life including the tempera on cardboard Women under the Apple Tree, 1920, seen in the exhibition. The brothers worked together, and Tymoffi painted frescoes and large scenes in the Kyiv Theatre of Opera and Ballet.

Kazymyr Malevych and El Lissitzky are memorable figures whose contributions continue to reverberate.

Malevych (1879-1935) adopted an approach known as Suprematism, which prioritised abstract visual language meant to express feelings and spirituality through colour and geometric shapes. His epochal Black Square was literally that, a painting “without any attribute of real life.” In one of many instances of the role of theatre in wider Ukrainian art development, this painting of a pure square is said to have first appeared in 1913, as the design for a stage curtain in the futurist opera Victory over the Sun.

Much later, Malevych abandoned abstraction for a more figurative style, as seen in Landscape (Winter), created after 1927. The current exhibition’s co-curator Katia Denysova has quoted art historians as saying that Suprematism first appeared in public not on canvases but deriving from the needlework of Ukrainian peasant women as advocated by Exter. Malevych returned to Ukraine in 1929 to teach at the Kyiv Art Institute and later moved to Leningrad where he was sidelined by the state. In every respect, political implications overshadowed Ukrainian modernism.

Lissitzky (1890-1941) was involved in Jewish cultural activities in Russia before going on to similar commitments in Ukraine. He designed propaganda and exhibitions for the Soviet Union. Under the influence of Malevych, Lissitzky became what was known as a Constructivist who believed that art should reflect the modern industrial world. His work eventually influenced the Bauhaus movement. Full of bright colours and bold shapes, Composition, from around 1918-1920 seems to owe much to his architectural breadth of view.

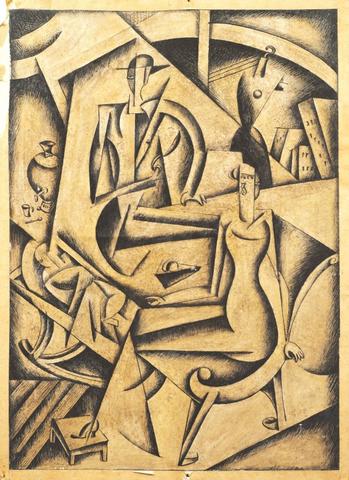

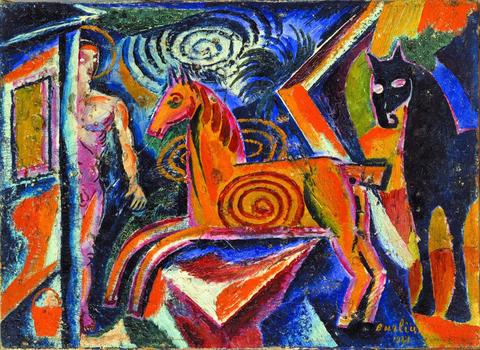

The art of Davyd Burliuk (1882-1967) who has been called “the father of Futurism” was influenced by Fauvist, Cubist, and Futurist styles. He was fascinated by Ukrainian folklore and Scythian culture, and according to an article in the Kyiv Post, gathered a group of writers, poets and artists which was known as Hylaea. That was the Greek name for the lands around the mouth of the Dnipro River, which Herodotus mentioned in describing the feats of Hercules, who in drawings in old maps was shown resting by the river after his victories.

Burliuk greatly admired Vincent van Gogh for his impassioned vision of nature and employed brilliant colours and vigorous strokes – the influence can be seen in his 1921 oil on canvas Carousel. In 1912, he and his wife lived in a hotel in Moscow where he and those of like mind produced the provocative Futurist manifesto “A Slap in the Face of Public Taste.” In early 1914, as the Futurists became more widely known, Burliuk, with the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky and Vasily Kamensky (a poet, painter and aviator) toured 17 cities of the Russian Empire, sporting animal faces, wearing gaudy waistcoats and with carrots in their lapels. Burliuk and his wife moved to the United States in 1922. Foreshadowing the New York modernists such as Jackson Pollock and their drip paintings he would “throw pigments with brushes, with a palette knife, smear them on my fingers, and splash the colours from the tubes.” In 1940, Burliuk petitioned the Soviet government to allow him to visit his homeland, but his request was turned down and he continued to be snubbed. Born in a village near Kharkiv, he was one of a large family of children of whom Volodymyr and Lyudmila also became artists, and brother Mykola a poet.

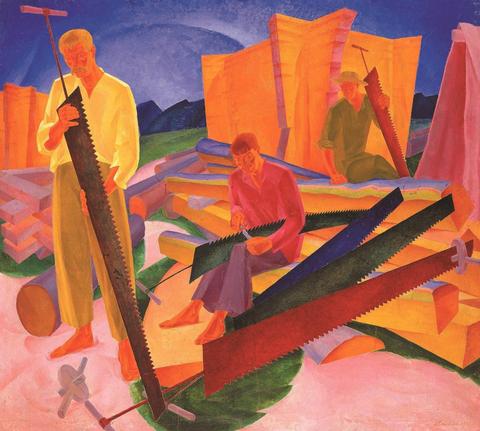

Oleksandr Bohomazov (1880-1930) was described in his homeland as “the Ukrainian Picasso” because of his succession of stylistic phases including Cubo-Futurism (1913-1917) and Spectralism (1920-1930). In 1914, he organised the exhibition Kiltse (The Ring) in Kyiv, of the works of 21 artists. The Royal Academy features Bohomazov’s bold oil on canvas Sharpening the Saws, from 1927.

A frisson of apprehension hangs over the procession of artist mini biographies because we know the awful fate that was to befall many. The purges, and abolition of independent art groups, wiped out the generation of modernist protagonists in Ukraine. Among the victims were Mykhalio Boichuk, who was executed in 1937, and his followers, many of whom were sent to labour camps. But their impetus was not squandered: for instance, since the Russian invasion in 2022, Boichuk’s works have gained increasing attention in Europe and the US.

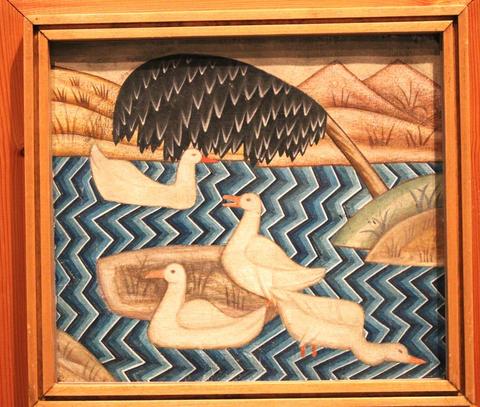

Painter and art restorer Mykola Kasperovych (1885-1938), a colleague of Boichuk, in 1917 joined his workshop at the Ukrainian State Academy of Arts. Among his paintings are The Creator of the Universe (1910) and an engaging study in tempera on cardboard, The Ducks (1920s). In 1924 Kasperovych became director of the Restoration Studio of the Kyivan Cave Monastery Museum, and later of the Restoration Studio of the All-Ukrainian Museum Village, in the grounds of the monastery. When the museum village was scrapped, Kasperovych worked as an art restorer in museums in Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Chernihiv.

Everything on display now was whisked out of Ukraine after the first stages of the Russian invasion of 2022, to avert the danger of destruction by bombing raids. Unesco has published a list of more than 400 cultural sites said to have been damaged since the incursion.

Konstantin Akinsha, an art historian, journalist and co-curator of the present exhibition, and others including Francesca Thyssen-Bornemisza, an avid contemporary art collector, in November 2022 gained approval from President Zelensky for the evacuation of cultural objects. The president provided a military convoy to escort the artworks, hidden in trucks, to the border with Poland, from which point insurers were able to provide coverage. The precious consignment arrived safely at Madrid’s Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza to start a tour taking in London, Cologne, Brussels and Vienna.

The exhibition is organised by Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, in collaboration with the Royal Academy, London; Museum Ludwig, Cologne; the Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels; Belvedere, Vienna; and Museums for Ukraine. Together with Konstantin Akinsha, it is curated by Katia Denysova, PhD candidate at the Courtauld Institute of Art, Olena Kashuba-Volvach, curator of 19th and early 20th-century art at the National Art Museum of Ukraine, and Ann Dumas, one of the Royal Academy’s most experienced curators.

In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900–1930sis at the Gabrielle Jungels-Winkler Galleries of the Royal Academy until Sunday October 13, 2024, 10am- 6pm Tuesday to Sunday and 10am-9pm Friday