A gallery view of MC Escher’s woodcuts Freighter, and Porthole.

The Amazing World of MC Escher: a master of graphic illusion mesmerises in new show at Dulwich Picture Gallery

By James Brewer

In spring 1936, the Dutch graphic artist Maurits Cornelis Escher – whose woodcuts and lithographs are famed worldwide for their extraordinary optical illusions and ‘impossible’ perspectives – took ship to sail the Mediterranean. Although reasonably well-off, he had written to the Adria Shipping Co offering to produce prints illustrating their ports of call in return for free passage and board. To his surprise, his offer had been accepted.

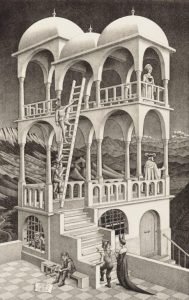

Belvedere, May 1958, lithograph. By MC Escher. Collection Gemeentemuseum Den Haag.

The two month voyage took him to Venice, Palermo and Genoa, where his wife Jetta joined him.

Two detailed woodcuts that resulted from that long cruise are among 100 works which feature in the Dulwich Picture Gallery exhibition The Amazing World of MC Escher (until January 17 2016). Transferred from its July-September 2015 showing at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, it is the first major UK retrospective of original work by the artist.

One of the Mediterranean woodcuts is named simply Freighter and is a masterpiece of marine art – there is no need for artistic trickery here. Escher was clearly fascinated by the interplay of ship’s paraphernalia. The exhibition notes say that “the complicated criss-crossing lines of mast and rigging make this unassuming woodcut a tour de force of printmaking technique. The thickness, character and finish of each line is carefully judged so that the cutting technique and the image depicted vie equally for our attention.”

His print Porthole is partly based on a photo taken in May 1936, when the ship was berthed in Savona, and partly on a drawing when he was in Malta on the return trip. “Ever the brilliant technician, Escher conveys the tone of a wall, and its slightly different tone when seen through the glass, and moreover adds the light reflections that play upon the glass – all through the simple criss-crossing of cut lines, ” say the curators.

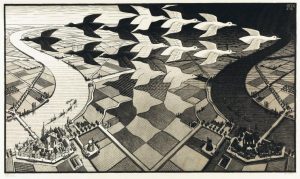

Day and Night, February 1938, woodcut in black and grey. By MC Escher. Collection Gemeentemuseum Den Haag.

This was the mystique of the sea captured by Escher on a voyage in which he plainly delighted.

Disembarking, Escher spent time at the great Alhambra palace in Granada, where he marvelled at the mosaic of tiles of interwoven patterns and launched a personal mission of expressing, as he saw it, eternity and infinity in a single print. He began, full-tilt, to develop his intriguing style in which reality metamorphoses into fantasy.

The Dulwich exhibition carefully traces the entire career of MC Escher (1898–1972) who forged his own artistic pathway at a time when printmaking was largely out of fashion in the established art world. The results were some of the most popular and familiar images of the 20th century.

+please read caption at the end of the article

His genius was to appreciate that what we see is always transient, and that a material scene has within it the power to transform into its inverse or opposite. His capacity for creating tessellations seemed endless: angels into devils and vice-versa, seabirds into cultivated fields, cities into chessboards. One of his devices for drawing infinity was a tableau of inter-locking fish.

Celebrated images include hands drawing hands (he was, like Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Dürer and Holbein, left-handed) to reveal the concept of eternity in art; staircases without an end; and self-portraits in the distortion of spherical mirrors. Here is as representative a collection as might be, supplemented by archive material from the collection of the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, The Netherlands.

Patrick Elliott of Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art.

Throughout he was a dedicated draughtsman and master of the fine line. When he took the plane-shifting type of exercise as one of his modules in art school in Haarlem, he had never thought that in elevated importance this would be the future of his art. The surrealists played with plane-enhancement, but Escher took this skill to what, forgive the expression, might be called new heights.

He moved from topographical themes of dizzying cliffs in Corsica and Amalfi (he travelled through Italy taking a bird’s eye view of landscapes, mountains, towns and buildings) to playing his tricks with reality: in Still Life with Mirror (1934) we see Escher using surreal illusion perhaps for the first time. Here is the exemplar of how obsessive he was about detail. The closest look at this work is repaid handsomely: who else could show so evidently the difference between the quality of the bristles on a toothbrush and those on a hairbrush?

Porthole. Woodcut from two blocks. By MC Escher. Collection Gemeentemuseum Den Haag.

Hampering his early recognition was the fact that he did not belong to any art grouping, said Patrick Elliott, senior curator of the Scottish gallery, but this is today seen as a plus. Mr Elliott said that Escher had been the Edinburgh institution’s most popular show after van Gogh. “He ranks alongside Dalí and Magritte, one of the giants of 20th century art. There aren’t many artists whose work makes your jaw drop, but he’s one of them. The odd thing isn’t that we are showing Escher’s work, it’s that few people thought of showing him before.”

Ian Dejardin, Sackler Curator at Dulwich, said that his images were better known than his name, and that probably every art student had one of his prints on their wall. In spite of his popularity he is difficult to pigeonhole. “He was a one-man act, ” said Mr Dejardin. “He never saw himself as part of a movement (but) it is difficult to think of an artist with a broader appeal than M C Escher. His images are so magical, and so incredibly clever, that he creates impossible images that feel utterly real, like the very best fantasy writers.”

Escher’s designs have been absorbed deep into popular culture, notably his tessellation technique as exemplified by the lithograph Reptiles (1943), where creatures emerge from a two-dimensional drawing into the 3D world. A coloured version of this startling piece was used on the LP cover of the group Mott The Hoople in 1969. His constructs have been adopted in films classic (Labyrinth) and contemporary (Inception), and been referenced in TV shows (The Simpsons, Family Guy) and even in the gaming app Monument Valley.

What were taken as his ‘mind-bending’ as well as logic-bending ideas appealed to the hippie generation of the 1960s, but the artist jealously guarded use of his images. He turned down a written request from Mick Jagger to contribute to a Rolling Stones album cover, as he seemingly had never heard of the rock star, and objected to being addressed familiarly by Jagger as ‘Dear Maurits.’

Whether or not that was a wise decision, his acuity of vision throughout his life made of his artistry a paragon of perfection.

The Amazing World of MC Escher is at Dulwich Picture Gallery until January 17 2016. www.dulwichpicturegallery.org.

+caption of photograph no 4: Relativity, July 1953, lithograph. By MC Escher. Collection Gemeentemuseum Den Haag.

All MC Escher works C 2015 The M.C. Escher Company The Netherlands.

All rights reserved. www.mcescher.com