Nikolai Astrup landscapes on show at Dulwich.

Painting Norway: Nikolai Astrup. First UK show of ‘messenger of the Norwegian Spring’ is staged by Dulwich Picture Gallery

By James Brewer

Although he spent much of his life amid rural tranquillity, one of Norway’s greatest 20th century artists was stirred by the folk memories of Viking exploits and culture that date back more than 1, 000 years. When he visited mountain farms, and walked among the old wooden houses with their turf roofs, Nikolai Astrup (1880-1928) reflected on the long tradition of the seafaring communities – not so much for their renowned skill in their longships, as for the beautiful crafts and designs they created — woodcarvings, jewellery and other artefacts. Such are the Viking achievements too often overlooked by non-Scandinavians.

March Atmosphere at Jølstravatnet. Before 1908. Oil on canvas. Private collection, Oslo.

Dwelling in a quiet landscape halfway between Bergen and Trondheim, Astrup was far from provincial, and touched by all the latest European artistic and intellectual developments.

At the same time, he was conscious of the history of the unification of Norway as a consolidation of small counties: first, under Harald Fairhair in the ninth century, and then in the 1270s when Norway adopted its first national legal code. He is one of the most Norwegian of artists, and Dulwich Picture Gallery is presenting the first UK exhibition of his paintings and prints. It is a magnificent show which repays digging into the context through reading the biographical and artistic research produced by co-curators Ian Dejardin, MaryAnne Stevens and Frances Carey, and others, for the catalogue.

Astrup’s home in the western Norway region of Jølster was in a splendid but remote setting, 218 km from the country’s then commercial capital Bergen, or 145 km as the crow flies. It is a journey that takes close to four hours by modern car. While dedicating himself to working and to family life in Jølster and remaining a quintessentially national artist (critics called him the messenger of the Spring of Norwegian Painting), Astrup travelled overseas to view contemporary and ancient art in Berlin, London (at the Tate he loved the work of Constable and Turner) and Paris (where at the Louvre he admired Greek vases and photographed Egyptian art). Many of his letters to friends, containing strong and articulate personal opinions on all facets of art, have thankfully survived. For instance, he distrusted the Impressionists because of their sense of trickery, as he saw it. This was an era when, as one Danish periodical said at the time, “artists of all nations are on the march.”

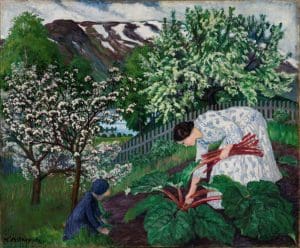

Rhubarb, 1911. Oil on canvas. The Savings Bank Foundation DNB/The Astrup Collection/ KODE Art Museums of Bergen.

He was keenly aware of international events, for instance praising the defence by Emile Zola of Alfred Dreyfus, the French army officer of Jewish background falsely accused of treason.

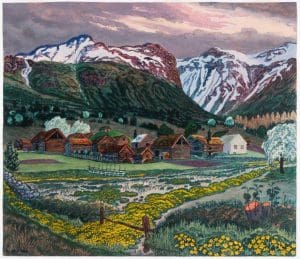

The beginning of the 20th century was an important time for affirming national cultural identity. Norway wrested independence from Sweden in 1905, when the artist was 25 years old. As the sense of national liberation flourished, his work grew to be considered a paean to the landscape that borders the fjord-like Jølstravatnet, and as MaryAnne Stevens says he was receptive to the burgeoning interest in Nordic myth and sagas. Jølstravatnet, described by an American writer as beautiful expanse of clear water, was becoming a tourist attraction. The lake was crossed several times a day by a small steamer, and a few kilometres away there were sea connections to Bergen.

Dulwich traces Astrup’s artistic development from his early years of realistic representative paintings, to the more experimental techniques after 1911. Throughout his life he was troubled by asthma and tuberculosis, which with pneumonia complications brought on his death. Tuberculosis was sadly common in his home region and had struck down several of his friends at an early age.

Marsh Marigold Night, c 1915. Colour woodcut on paper. The Savings Bank Founation DNB/ T he Astrup Collection/KODE Art Museums of Bergen.

In Astrup’s work there is much calm contemplation of the intensified colours in everyday scenes around him. As he put it, “the close proximity of the sea makes the air so pure that all colours appear intact as though they are near.” Or as Ian Dejardin, Sackler director of the gallery, said: “In western Norway he could see right through to the colour, no matter how far away.”

At one point the artist wrote, “I wished… to wash myself in the colours of western Norway, ” but as Ms Stevens qualifies, there was a more nuanced dialogue with other influences.

Ms Stevens compares his “ecstatic” response to his Norwegian landscape to the musical reaction by the composer Edvard Grieg to the same stimulus.

Astrup inherited from the Vikings and their successors an appreciation of folk crafts, making designs for woven cloths as did his wife Engel (who was pregnant for much of her married life) and originated what we would today call an ecological garden by gathering plants from the region to bring his property at Sandalstrand, to which the family moved – from Ålhus on the opposite bank of the lake – in 1913.

Nikolai and Engel transformed Sandalstrand from its rudimentary state into the most distinctive and important artist’s garden in providing him with many artistic motifs which became the subjects of his paintings and prints such asRhubarb (1911) and Spring in Jølster (1925). He was famous in the district for his wine made from rhubarb, 10 varieties of which he propagated at Sandalstrand. Fruits and flowers produced in the short growing season of the garden were used to decorate the interior of the farm and to create works such as Interior Still Life: Living Room at Sandalstrand (c 1921).

The farmstead Sandalstrand is today known in honour of the painter as Astruptunet and is a popular visitor attraction.

The farmstead Sandalstrand is today known in honour of the painter as Astruptunet and is a popular visitor attraction.

In a charming picture, Birthday in the Parsonage Garden, Engel is shown wearing a dress of hand-printed fabric based on a picture she had seen in a Paris magazine. The dress, seen too in a painting by Astrup of his beloved rhubarb patch, survives and is on display at Astruptunet.

Dulwich has gathered 120 oil paintings and woodcuts, many on public display for the first time, supplemented by archive material which offers many insights into the practice of this remarkable man.The first room takes us right into the fjord and lake scenery around Ålhus and domestic views of his father’s parsonage and garden. His respiratory problems meant that he was often confined to the house, but he came at a young age to record everything that was accessible to him. The heavy rainfall which greens the area is captured inRainy Atmosphere beneath the Trees at Jølster Parsonage (before 1908). Farmstead in Jølster (1902) and other canvases illustrate Astrup’s determination to represent both foreground and background – an almost 360 degree view – with equal intensity.

When he returned to Jølster from studying at the Royal School of Drawing in Kristiania, his output continued to be influenced by the vivid impressions and images remembered from his childhood. Mr Dejardin said of Funeral Day in Jølster: “What I love about this is the absolute stillness, the limpid, realistic landscape… and when you look closely you will see what is happening. There is a funeral.”

The fairy tale strain was frequently lurking. In Grain Poles the subject matter is akin to an army of marching trolls, even with the suggestion of a face. Elsewhere there is the spirit of ‘troll’ trees; and a mountain known as the Ice Queen (1917) is shaped by Astrup into a naked woman in repose.

Astrup appears to have been uninhibited by his Lutheran background: witness a series of Midsummer Eve festival bonfire paintings, which shocked conservative society because of the pagan origin of such festivals and the free mixing of young men and women. In Midsummer Eve Bonfire (1915) the couples dance merrily to the tune of the Hardanger fiddle.

Engel Astrup, as seen in Birthday in the Parsonage Garden, 1911-1927. Oil on canvas. The Savings Bank Foundation DNB/The Astrup Collection/KODE Art Museums of Bergen.

In another form of picturing the landscape and traditional way of life and folklore, Astrup expanded the artistic possibilities of woodcuts, as did the better known Edvard Munch (whose work Astrup says at one point he “cannot abide” although he was pleased when Munch bought a couple of his prints).

Astrup was often not satisfied with the results of the woodcut impression, and he would apply texture and oil paints with a brush. The woodcuts on show at Dulwich, whether monochrome or coloured, are a delight. See for instance A Clear Night in June (1905–7), and his largest print Foxgloves which is displayed alongside a related oil painting of 1909.

Mr Dejardin said: “Hailed even as an art student as the great new hope of Norwegian art at the turn of the 20th century, Astrup deserves to be celebrated outside his native Norway. In painting he rejected the stylistic trickery of aerial perspective, resulting in canvases of intense immediacy and brightness of colour; in prints he followed his own innovative path, laboriously reworking his woodcuts so that every print is a unique work of art, and – as a final work of art in its own right – he built himself a home, Sandalstrand, on the precipitous shore of the lake that must be one of the most beautiful artists’ homes in the world.”

Painting Norway: Nikolai Astrup (1880-1928) is organised by Dulwich Picture Gallery with Henie Onstad Kunstsenter and Kunsthalle Emden. Principal collaborator is Savings Bank Foundation DNB. The exhibition continues until May 15 2016.

Caption of the fifth picture:Spring Night and Willow, 1917/after 1920. Colour woodcut on paper. The Savings Bank Foundation DNB/The Astrup Collection/KODE Art Museums of Bergen.