Lesvos: Between Hope and Despair. Margarita Mavromichalis shows London her moving photo series

By James Brewer and John Faraclas

In a series of 35 dramatic photos on display at the Hellenic Centre in London is crystalised the refugee crisis that gnaws at the eastern Mediterranean region, and the whole continent.

Through her camera lens, Margarita Mavromichalis has starkly recounted the realities, harsh and harrowing, for thousands of people in limbo on the periphery of the European Union.

At her first solo show in London, the exceptional photographer appealed to what might be called the civilised world to address the plight of asylum-seekers with fellow-feeling.

More than 6,500 people have been living as best they can in shipping containers and flimsy tents at the squalid Moria refugee camp on Lesvos. The number is way beyond the detention centre’s official capacity of 3,100. There are a further 2,000 in a nearby area.

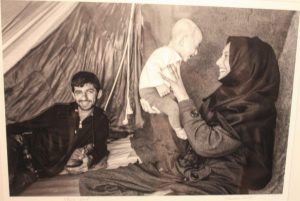

In a short speech at the private view of the photo exhibition, Margarita – “I usually like to hide behind the camera” – said that she was highlighting an aspect of humanity “that is very close to my heart.” The refugees had crossed dangers on land and over rough sea, out of pure desperation, seeking a place to realise their hopes for a better life. Her images showed emotions that we could all relate to. The conflicting feelings of desperation and hope were manifest in their faces.

Greece lacked the resources to cope with something that came at a difficult time for the country, she said. The country had shown its generosity, “but much more needs to be done.”

“The numbers of people on the move around the world are just staggering and we all have to come to terms with the reality in the most humane way.”

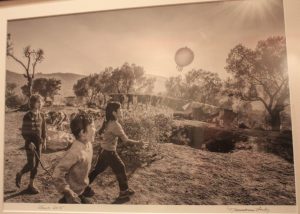

The Greek photographer who lives and works in London drew attention to the two images that end the sequence, and the clear contrast between them. The first was taken on her visit to a graveyard for the many who “did not make it” and in one section most of the buried were children under the age of 10. The final image showed three children playing with a balloon they made from a surgical glove.

Her stirring call for action, optimism and compassion was greeted with prolonged applause from the throng at the Friends’ meeting room of the cultural centre.

Margarita’s photography is a masterclass in composition, balance and extraordinary subtlety. Her juxtapositions – such as adjacent studies of sunrise and sunset – point to the conflicting societal response to the waves of migration that are as much a factor of human history as they always have been. For Lesvos, she chose to make black and white prints to set off the subject matter and impel the viewer to focus as sharply as she does on the human condition.

It is hardly surprising that for her Lesvos photos she has just been named as winner of the documentary and human rights categories of the 12th edition of the Julia Margaret Cameron awards (she also took first place in the people category for a set entitled “A British Social” and first place in self-portraiture for “Unedited”).

The scheme honours Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) who was an early British photographer known for her soft-focus portraits of celebrities of her time. The competition is open to women working in all photo mediums and was entered by 760 photographers from 72 countries in all categories. The prize will be formally presented to Margarita when she has a solo exhibition in Barcelona in April 2019.

Margarita’s work is meanwhile featuring at the Yixian Festival, Atlas of Humanity in China, in November and December 2018. The festival is inspired by the Unesco declaration on cultural diversity.

On her own initiative, Margarita began documenting the refugee crisis on the Aegean island in 2014, with her latest visit being earlier in 2018.

The portraiture of her selected images speaks volumes. In a note accompanying the exhibition, she writes: “We can argue about politics, the economy, religion and all else we can think of, but there should be no arguments when it comes to human lives in peril. I come from a country, Greece, that has been facing the worst economic crisis it has ever known in modern history and its people have been suffering more than anyone living outside of the country will ever know. However, Greece has had to deal with yet another drama, the humanitarian crisis of the refugees.”

Thousands of people had flooded the nation’s coasts and many lost their lives on the way. “They arrive in boats, piled like cattle, hungry, wet, cold and exhausted. The few belongings they own fit in a backpack and some don’t even have that.” Upon safe arrival after the perilous crossing, some dance and sing, others burst into tears.

She was congratulated on her achievements at the private view which saw a substantial turn-out of friends and admirers. Among the gathering were ambassadors (she is married to His Excellency Dimitris Caramitsos-Tziras, ambassador of Greece to the Court of St James), former envoys and other diplomats, and people from shipping, business, the arts, entertainment, broadcasting, film, books (including author Victoria Hislop, who most recently regaled an audience at the World Travel Market London 2018 with stories of her love for Greece and its islands), music and science. The shipping-related contingent included International Maritime Organization secretary-general Kitack Lim, Stamos J. Fafalios who is also the Hellenic centre’s vice chairman of the executive board , Alex Kedros, Nick Skinitis, Sofia Konstantopoulou, Stratos Hadjiyiannis and many others.

A range of reactions to the images came in private conversation with the viewers. “There is no misery,” exclaimed one guest, scanning the faces in the photos which exuded a determination to make the most of their lot. Another spectator was transfixed by the eyes of the refugees held in a wire-mesh pen.

Some of the asylum-seekers have been on the island since 2015, for It can take years before their cases are processed. On some days, they spend hours waiting in line for food.

Margarita offered an insight into how one-to-one connections strike a chord when residents met the refugees. She said that the locals told her that history was repeating itself. Their forefathers were refugees when they arrived from Asia Minor. “The only difference”, they said, “is that no-one was waiting for us when we arrived. We were alone, slept in fields out in the cold and we had nobody to provide for us. We know very well what these people are going through, and we want to help.”

“I do not believe that my images do enough justice to what I have witnessed on my trips to Lesvos,” said Margarita. “However, if I manage to touch even a few people with these images, I will consider myself successful. There are still too many people out there who will conveniently shy away from this reality.”

l to r: IMO’s Secretary-General Kitack Lim, Margarita Mavromichalis and her husband Dimitris Caramitsos-Tziras.

Agatha Kalisperas, director of the Hellenic Centre, reviewed Margarita’s career, relating that she comes from a family of Greek diplomats and has spent her life living and traveling in many countries, and speaks five languages.

Mrs Kalisperas said that Margarita moved to New York in 2009, where she continued her studies for three years at the International Center of Photography. She returned to Greece from 2013 to 2016 where she devoted most of her work to covering the refugee crisis as it developed on Lesvos.

Benjamin Ward, deputy director of the Europe and Central Asia division of Human Rights Watch, said that Margarita’s pictures showed a shared humanity. “We often forget that basic shared humanity,” he said.

Mr Ward observed that the number of people making the crossing had fallen considerably since 2015-16, “but significant numbers of people continue to arrive” and a Human Rights Watch team which visited a few weeks ago saw nursing mothers siting in unheated tents with their children.

He insisted that “the islands are not equipped to deal with them,” but “the people of the islands have been welcoming and the local authorities have done what they can.”

It has been reported elsewhere that about 23,000 people have arrived in the Greek islands in 2018, down from 850,000 in 2015.

The willingness of other European governments to assist had reduced, said Mr Ward. Although the Greek authorities had moved quite a lot of the refugees, there was pressure to keep people on the islands and not move them to the mainland. “We are saying that other governments need to change their approach.” An encouraging example was a pilot programme by Portugal to take 100 asylum seekers from Greece.

Mr Ward said: “It is a challenge than can be met humanely in accordance with our values and securing our borders if it is done collectively.”

A Times journalist, Roger Boyes, added his support for Margarita’s project, saying that Greek citizens’ response to the swelling numbers of refugees had been incredibly positive. Climate change and “everything that is happening in sub-Saharan Africa” would continue to drive out people. The western world forgot about such countries, and it beggared the imagination that we did not have politicians that could express themselves more adequately on the subject in the UK, and across the West.

Lesvos: Between Hope and Despair, photography by Margarita Mavromichalis, is at the Hellenic Centre, Marylebone, London, until November 29, 2018.