Philip Guston, artist who mocked the banality of the Ku Klux Klan, in retrospect at Tate Modern

By James Brewer

At the end of the 1960s, the artist Philip Guston turned his back on his years of abstract output, to produce large-scale paintings of ghastly but comic-style hooded characters. He posed the question of who and what was behind the mask – the mask being the white hoods of the savage Ku Klux Klan fanatics.

Tate Modern, in its landmark retrospective of Guston (1913-1980) delves deep into his 50-year career, of which the most memorable period can be said to be his depiction of the Klan as ‘everyday’ perpetrators of racism. His ridiculing of the Klan as banal delinquents was of a piece with his lifelong disgust at such barbarisms. He said of the Klan: “They plan, they plot, they ride around in cars smoking cigars. We never see their acts of hatred. We never know what is in their minds. But it is clear that they are us. Our denial, our concealment.”

Musa Mayer, the artist’s daughter, and head of the Guston Foundation has said more recently: “My father dared to unveil white culpability, our shared role in allowing the racist terror that he had witnessed since boyhood when the Klan marched openly by the thousands in the streets of Los Angeles.”

In Guston’s garish pictures, the hooded figures can be seen driving around town, waiting at home, or even with paintbrush in hand making art. His paintings satirise attempted projections of violence and intimidation which are laughable in one sense, but unsettling in being so trite. The Klan had a long history of thuggery, having been founded in 1865 (the name Ku Klux Klan comes from the Greek kyklos, meaning circle, and the Gaelic word clan) being especially active in the first third of the 20th century, and again in mid-century, with night assaults on African Americans and their homes, and lynchings. The masked bands were able to take the law into their own hands as their “invisible empire” infiltrated sections of the police, sheriffs, members of state legislatures and even judges.

Guston sometimes refers to the murderous crimes of the Klan by splashes of red paint on the sinister hoods and such devices as a jumble of legs trailing a car. A gruesome, peachy early morning light is a reminder that evil can be present even in the glow of dawn. This suffusion of a rosy, pink hue became a trademark of Guston’s work of this type. His stylisation of the figures was of an innocent inspiration: the comic strips he had loved as a boy, particularly Krazy Kat, which ran in publications from 1913 to 1944 with surreal landscapes and twisted character relationships.

By presenting images of Klansmen carrying out activities that are ordinary for most people – the hooded emblem made to appear even on a school blackboard – Guston suggests that evil lurks everywhere. The paintings and those that followed established him as one of the most influential painters of the late 20th century.

Guston had renounced the abstraction he had practised in the 1950s and 1960s and embraced figuration. In chronicling his explorations, Tate Modern’s retrospective is a bold survey of an artist responding to personal inner dilemmas and to political outrages over the decades.

The exhibition itself has its own turbulent history, as a touring show that was postponed by four institutions, with one curator resigning before being suspended. It was due to open in June 2020 at the National Gallery of Art Washington DC before being moved to the Museum of Fine Art Houston, Tate Modern and finally the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Covid struck and an eight-month delay was announced, and then the four institutions caused dismay by postponing the opening until 2024 “until a time we think that the powerful message of social and racial justice that is at the centre of Philip Guston’s work can be more clearly interpreted”. This was a reaction to the atmosphere of huge protests over the murder of George Floyd, but the delay was ultimately recognised to be too extreme a response, and after consultations with curatorial experts, the show has gone ahead.

The delay allowed the show’s curators to conduct further research and make a film of a mural which the artist helped create in Morelia, Mexico (The Struggle Against Terrorism, 1934-35). With Reuben Kadish and Jules Langsner Guston had travelled to work on the huge fresco which cries out in resistance to violence and persecution, from medieval times to the rise of fascism in Europe and includes three Klan-like figures. At Tate Modern, the mural is projected at a scale of 5 metres tall. Guston was an assistant to muralist David Siqueiros who described him as one of “the most promising painters in either the US or Mexico.”

The exhibition is the first major retrospective on the artist in the UK in nearly 20 years, and one third of the work has never been seen before in the UK. Through more than 100 paintings and drawings from Guston’s momentous career, the show offers new insight into his formative early years and activism, and his genre switches, as an artist who defied categorisation,

It begins with Guston’s early years in Montreal as the child of Jewish immigrants who had escaped persecution in present-day Ukraine, and the family’s subsequent migration to Los Angeles in 1922. He became serious about drawing at the age of 12 and pored over reproductions in books of Renaissance paintings. He loved the large frescoes, and that awakened is ambition to be a great painter in that tradition, his daughter suspects. Largely self-taught, he was only briefly at art school alongside Jackson Pollock, with whom he shared an interest in European contemporary art, especially surrealism and the work of Pablo Picasso.

Against a backdrop of rising fascism and Ku Klux Klan activity, Guston’s work soon became increasingly political. Moving to New York in 1936 and changing his name from Phillip Goldstein to Philip Guston in 1936, as antisemitism in America and around the world spread, he created murals for the government funded Federal Art Project, before in 1948 making the first of three trips to Italy. Returning to the US, he turned towards an increasingly abstract language, becoming an influential figure in the New York School alongside Pollock, Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko.

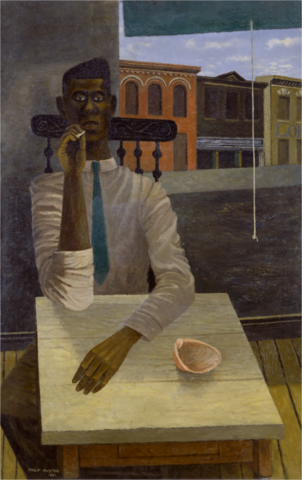

Works from the 1940s show him exploring portraiture, including a self portrait and a portrait of his wife Musa McKim. and Sunday Interior, which depicts an unknown sitter. At the time, he was a lecturer and artist in residence at State University of Iowa.

By the 1960s, Guston had helped pioneer a form of art known as neo-expressionism. As he struggled to find his new figurative way, he began drawing objects around him: ink jars, light bulbs, food, and books. “I must have done [i.e., pictured] hundreds of books,” he recalled. “They’re just such a simple form, but it seemed filled with possibilities… and then some of the books started looking like stone tablets. They keep changing.”

Calling American abstract art ‘a lie’ and ‘a sham,’ he made paintings such as satirical drawings of Richard Nixon during the Vietnam War. In 1966, he helped raise money for an organisation providing legal aid for activists and supported education and Black voter registration. He was troubled by episodes such as the police violence against protesters at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago. This and other events triggered his memories of the Klan and renewed awareness of the horrors of the Holocaust. It was the artist’s responsibility to “un-numb oneself to the brutality of the world,” he said, continuing: “that’s the only reason to be an artist… to bear witness.” He took up the question of societal complicity in violence and racism, and said of several paintings of Klansmen: “They are self-portraits … I perceive myself as being behind the hood … The idea of evil fascinated me … I almost tried to imagine that I was living with the Klan.”

A major show of paintings with hooded figures at New York’s Marlborough Gallery in 1970 included The Studio, in which he interrogated himself as well as society at large. Critical reaction was negative. After a spell in Italy, at his studio in New York state he took on a new artistic language of giant eyes, piles of legs, abandoned shoes, and everyday objects. The truncated body parts can be seen as skewering Holocaust barbarism.

The final decade of Guston’s life was, quietly, his most productive, when he created some of his most complex work. His late paintings were often dreamlike, with objects in precarious balance. Flatlands, from 1970, is a kind of catalogue of much of his late imagery, hoods and all.

Legend, from 1977, is littered with items from the studio, including an empty bottle, cigarette butts and a wooden wedge used to stretch canvases. The painting even draws visual parallels between a horse’s rear end and Guston’s sleeping head. The horse may be a reference to one of his favourite books, Red Cavalry by Isaac Bebel, from 1926. That book narrates events of the Polish-Soviet war of 1918-21, including persecution of Jews in what is now Ukraine, from where Guston’s parents had fled. There is a further reference to his personal history in a large canvas titled Aegean from 1978 and another, Black Sea, in which the crudely shaped heel of a shoe bestrides a dark green stretch of water. It was from Odessa that his parents emigrated in 1905. He often gave titles to his works only after they were finished. Aegean with its cloudless blue sky might evoke the Olympic battle of Greek gods.

Collaborating widely across disciplines, he was inspired by the poets of the time, among them by his wife, the artist and poet Musa McKim (1908-1992). Continuing to be wrapped up in his artistic visions, in 1977 he painted Sleeping, a monumental image of the artist in bed, vulnerable and dreaming. To the end, Guston remained as rebellious as ever, creating combinations of dream-like images and nightmarish figures.

In 2013, Guston’s abstract expressionist painting from 1958 To Fellini set an auction record at Christie’s when it sold for $25.8m. The work was an homage to the Italian film director Federico Fellini, whose dramatic imagery appealed to Guston.

The exhibition is co-organised by Tate Modern, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the National Gallery of Art, Washington, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Tate Modern’s presentation is curated by Michael Wellen, its senior curator of international art, and Michael Raymond, assistant curator of the same discipline.

Captions:

The Studio. 1969. Oil on canvas. Promised gift of Musa Mayer to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Legend, 1977. Oil on canvas. Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Museum purchase funded by Alice Pratt Brown Museum Fund.

Musa, 1942. Oil on canvas. Promised gift of Musa Guston Mayer to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Aegean, 1978. Oil on canvas. Private collection. Olympic. Philip Guston. The Estate of Philip Guston. McKee Gallery, New York

By the Window, 1969. Oil on canvas. (Roman Family).

Sunday Interior, 1941. Oil on canvas. Courtesy Private Collection © The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser & Wirth.,

Flatlands, 1970. Oil on canvas. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Gift of Byron R. Meyer. © The Estate of Philip Guston.

Philip Guston, the exhibition is at the Eyal Ofer Galleries, Tate Modern, London SE1, until February 25, 2024.