Impressionists on Paper: Degas to Toulouse-Lautrec, a stunning show at the Royal Academy

By James Brewer

Here are van Gogh, Cézanne, Degas, Gauguin, Monet, and other luminaries of the late 19th century, but not quite as most people know them.

A rich, well-rounded exhibition at London’s Royal Academy of Arts gives an insight into the vision and techniques of some of the world’s best-loved artists. It is a catalyst for yet another resurgence of interest in the irrepressible Impressionists. Causing a stir throughout Europe and beyond, the Impressionists in their varied ways revelled in the latest art techniques and applications, and used pastels, watercolours, tempera, and gouaches in convenient forms.

This allowed them to produce sketches that claimed a shared aesthetic with traditional, formally rendered canvases. They extracted the maximum impact from sometimes the minimum of lines. Their innovations unveiled a new pageant of treasures.

Presenting Impressionists on Paper: Degas to Toulouse-Lautrec the Royal Academy celebrates a polyphony of endeavour and is a valuable opportunity to view works rarely put on show because of their fragility. The institution can only be congratulated for mining this glittering seam of pièces de résistance.

Van Gogh is familiar to millions for his celebrated chair and pipe, sunflowers, starry night and much more painted thickly with oils in dramatic colours. He insisted though that drawing was “the root of everything” and made more than 1,100 drawings. He sold few works, but this did not still the pen of the consummate draughtsman for he was able to exploit a bountiful pictorial harvest of subjects: people at their chores in the fields and domestically. Many such studies he effected from 1883 to 1885 while living in the village of Nuenen in North Brabant, to where his parents had moved. His understanding of their ways fed into his first masterpiece The Potato Eaters, which shows a family tucking into a dish of potatoes and eager for their cups of coffee.

In his most distinctive pen drawings, van Gogh applied ink in an enormous variety of strokes using both metal and reed nibs. He might use a mixture of inks, charcoal, or chalk in a single drawing. It must be remembered that over the years, his pen sketches have degraded from black and purple into brown.

Among his many rural scenes, the last made in Nuenen was of a group of cottages in winter. Thatched Roofs in ink, graphite, and gouache on paper, and held by the Tate Gallery, is one of the gems at the Royal Academy show. Also on view is a drawing from 1885 of a peasant woman carrying wheat in her apron, in black chalk, grey wash and gouache on laid paper, from the Kröller-Müller Museum, which is located deep in the Netherlands’ De Hoge Veluwe National Park, and which possesses the world’s second largest van Gogh collection.

Before moving to Nuenen, while starting his career as an artist, van Gogh made a series of city views, one of which was The Entrance to the Pawn Bank, The Hague. He drew this in 1882 on laid paper in pencil, pen, and brush in ink, opaque white watercolour, and grey wash. His uncle Cornelis van Gogh in Amsterdam paid 2.50 guilders for what was the first paid commission from an artist whose oeuvres would one day sell for millions of dollars.

From his time in Paris, 1886-88, where he honed his personal style, van Gogh mastered a combination of graphite, chalk, watercolour, and gouache in such as The Fortifications of Paris with Houses, now in the collection of the Whitworth, University of Manchester.

Axel Rüger, the secretary and chief executive of the Royal Academy, knows such works well, for he is a former director of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. He emphasised that the works in the show are at risk from exposure to light, and many are normally kept in cabinets. Being framed soon after being composed has helped preserve many. Those in pastel especially are flimsy and vulnerable to vibration. The Van Gogh Museum and others continue to battle against the effects of chemical reaction of the inks, which eat into the paper.

The RA chief underlined that from the moment the Academy was set up, drawing was its priority in training artists. He cited the German word handzeichen as expressing the predominance of the hand in drawing.

A rollcall of incomparable craftsmen and craftswomen is behind the 80 works on paper. They include Mary Cassatt, Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Paul Gauguin, Eva Gonzalès, Claude Monet, Berthe Morisot, Odilon Redon, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Georges Seurat, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, van Gogh, and lesser lights, contributing to a vivid history of how artists seized with gusto on new means of expression.

The Impressionists, who were once also known as the Independents or Intransigents, came to prominence during the late 1860s and early 1870s, first exhibiting in Paris as a group in 1874. Through many differing approaches, they shared enthusiasm for scenes from everyday life in city and countryside. Vivid colour, a quickfire touch, and unconventional viewpoints, with in many cases a deliberate lack of finish, let them capture the fleeting effects of light and nature. Many of the drawings might be relatively unknown today, but their impact was as radical as their paintings.

Artists were newly enabled by the portability of drawing materials – pencil, pastels, watercolours etc – and the new dyes that were available. Japanese paper and different types of board suited their styles and facilitated direct observation and trial and error. The eight Impressionist exhibitions in Paris included many works on paper, and dealers who recognised a commercial opportunity in showing and selling such works encouraged the trend.

The mood of visitors to the RA is borne aloft from the outset by seascapes and other works from the early years of the 1860s and 1870s including Eugène Boudin’s glorious display of scattered light Sunset over the Sea in pastel on buff paper. French landscape painter Camille Corot called Boudin “the king of skies.” Degas makes an early appearance with his enigmatic Woman at a Window of 1870-71 (housed by the Courtauld, London), done in essence which is oil paint dissolved in turpentine. Among those who favoured pastel was a one-time pupil of Edouard Manet, Eva Gonzalès, represented here by a delicate meditation from 1879 entitled The Bride, a portrait on canvas of her younger sister and frequent model, Jeanne Gonzalès, who was an artist in her own right. This study has been dated to 1879, shortly after Eva’s marriage. For the portrait, Eva, who would die in 1893 at the age of only 36, lent her sister her own satin wedding dress.

At the Impressionists’ final group exhibition, works included one of Monet’s luminous landscapes in pastel, Cliffs at Etretat: The Needle Rock and Porte d’Aval, from around 1885 (National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh). Monet played down his history with pastels despite his using the medium with flair, promoting the notion that he always worked straight onto canvas. The Royal Academy in 2007 staged the first exhibition devoted to the pastels and drawings of Monet, highlighting 80 works of that often-overlooked aspect of his talent,

Pierre-Auguste Renoir began to work with soft chalk and pastel after his large paintings met a disappointing response. The technique, which he used both for preparatory studies and finished works, helped him to regain commercial success. To illustrate his skills, the Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge, has lent The Picnic, of around 1895, which is in sanguine (reddish-brown chalk) and black chalk on paper. It warmly echoes the artist’s appreciation of the countryside as a place for relaxation. Renoir praised the invention of handy metal paint tubes, saying: “Without paint in tubes, there would have been… nothing of what the journalists were later to call Impressionism.”

Camille Pissarro’s maxim was: “It is good to draw everything, anything – when you have trained yourself to see a tree, truly you know how to look at the human figure.” Among the best-turned of his scenes of life the community where he lived to the northwest of Paris is The Market Stall from 1884. Such compositions he sometimes prepared with many figure studies. A finished work such as The Market Stall reveals Pissarro’s skills in integrating those figures realistically in their quotidian setting. In this picture, he handles watercolour, tempera, and chalk with a panache that has all the stamp of a grander-scale painting.

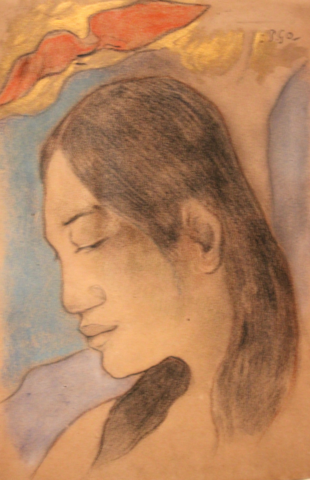

In 1892, the year after he arrived in Tahiti, Gauguin (1848–1903) drew, probably from life, Head of a Tahitian Woman. For the portrait of the seemingly unadorned youthful female, he used coloured chalks heightened with pastel. Her reflective expression embodies the spirituality and mystery with which he as a European of the epoch objectified very young Polynesian women. In that context, while on the island Gauguin met a girl of around 13 who became his ‘native wife.’

The explosion of creativity on the walls of the exhibition continues to weave its spell as it plucks delights from the drawing boards of the 1890s and 1900s. Among other glories of that golden age of pastel are the drawing by Degas of ballet dancers, his famed voyeuristic tendencies evident as he chronicled the young women at rest, one of them yawning after her exertions.

Degas was a great student of movement, obsessed by poses or combinations of poses he observed, re-using them on papers of different colours – he had been impressed by the new Japanese prints that were popular. Degas began to use pastels after 1880.He found their saturated colours well suited to the chromatic effects he sought, fixing and superimposing layers of powdery pigment.

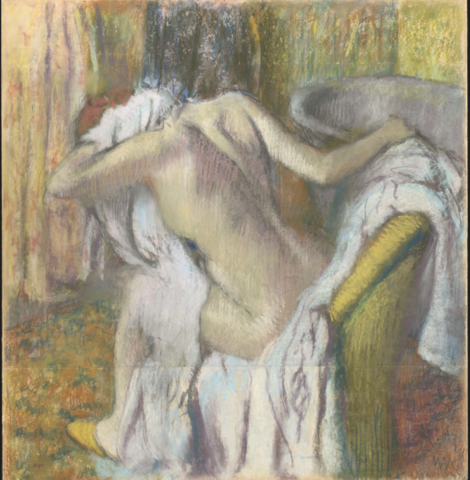

In a series of nudes, he depicted real women engaged in everyday washing and bathing. This was a deliberate snub to the tradition of the classical nudes of ancient Greece and Rome. He wrote: “Hitherto the nude has always been represented in poses which presuppose an audience, but these women of mine are honest and simple folk… It is as if you looked through a keyhole.”

Of a piece with this outlook is his pastel After the Bath, Woman Drying Herself, from between 1890 and 1895, courtesy of London’s National Gallery, whose curators commented: “A woman sits beside a bath, drying her hair… The ungainly but authentic-looking pose makes it easy to believe that Degas was present in the woman’s room, catching her before she could straighten herself. She was actually a model posing in his studio and would have held the position for some time while Degas made the preliminary drawing.”

The experiments of Degas with pastel were echoed by his friends especially the American Mary Cassatt and the Venetian Federico Zandomeneghi who arrived in Paris in 1873 and 1874 respectively. The former was one of the few female artists of such circles alongside Berthe Morisot. Mary first caught sight of Degas’s pastels in an art-dealer’s window. Her 1894 study in pastel on paper Portrait de Marie-Thérèse Gaillard is of the six-year-old daughter of a patron and friend and is emblematic of her images of the social and private lives of women, including the intimate bonds between mothers and children.

The final section includes examples of Cézanne’s contemplative watercolours and of his compositions with flowerpots, the latter a now a popular item with poster collectors. Cézanne spoke of the centrality of watercolour: “The more the colours harmonise, the more precise the drawing becomes.” Focusing on motifs associated with his native Provence, “he created timeless worlds with spare strokes and patches of translucent colour,” say the curators. Close by we can marvel at Odile Redon’s glowing outré and poetic reveries, such as Two Human-Headed Flowers in a Vase, in charcoal done on paper on board from 1880; and be reminded of the zest of Toulouse-Lautrec’s Montmartre’s pleasure haunts.

Exiting the final room of the exhibition is akin to leaving a gilded cage. That is a tribute both to the wonders on display, and to the skills of Ann Dumas, one of the Royal Academy’s highly experienced curators, and Christopher Lloyd, author and Surveyor of The Queen’s Pictures from 1988 to 2005, who together worked to organise the project for three and a half years.

The Royal Academy reminds us that the French avant-garde’s contribution to drawing and the remarkable range of their production had far-reaching consequences, including landmarks in 20th century art such as Abstract Expressionism.

Captions in detail:

Head of a Tahitian Woman, 1892. By Paul Gauguin. Coloured chalks and pastel heightened with gold paint on wove paper. Private collection.

The Fortifications of Paris with Houses, 1887. By Vincent van Gogh. Graphite, black chalk, watercolour, and gouache watercolour. Photo: © The Whitworth, University of Manchester. Photography: Michael Pollard.

Thatched Roofs, 1884. By Vincent van Gogh. Ink, graphite, and gouache on paper. Tate. Bequeathed by T Frank Stoop, 1933.

The Entrance to the Pawn Bank, The Hague, 1882. By Vincent van Gogh. Graphite, pen, brush and ink, watercolour, and grey wash on laid paper. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation).

Sunset over the sea, c 1860-1870. By Eugène Boudin. Pastel on buff paper. The Syndics of Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge.

After the Bath, Woman Drying Herself, c 1890-95. By Edgar Degas. Pastel on wove paper laid on millboard. The National Gallery, London. Bought 1959. Photo: © The National Gallery.

The Bride, 1879. By Eva Gonzalès. Pastel on canvas. Palais Princier de Monaco.

Study of a Woman from Behind, 1890-97. By Federico Zandomeneghi. Pastel on cardboard. Galleria D’Arte Moderna, Milan. Photo © Comune di Milano – All Rights Reserved.

Portrait de Marie-Thérèse Gaillard, 1894. By Mary Cassatt. Pastel on paper. Private collection. Photo: © 2007 Christie’s Images Ltd.

The Market Stall, 1884. By Camille Pissarro. Tempera and watercolour over black chalk on board. Glasgow Life Museum (Burrell Collection).

The Picnic, c 1895. By Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Sanguine and black chalk on paper. The Syndics of Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge.

Impressionists on Paper: Degas to Toulouse-Lautrec is at the Royal Academy of Arts until March 10, 2024.