By James Brewer

Her Bed-in with John Lennon in the cause of world peace; the once-banned Bottoms film; the confusion of an all-white Chess Set; a ‘refugee boat’ on which to chalk personal and political messages: such, together with re-runs of other classic ‘happenings’ bring the cool and conceptual world of Yoko Ono to London again.

Staged by Tate Modern, this is the UK’s largest exhibition celebrating the work of the gentle art rebel Yoko Ono although similar extensive displays have taken place in the last few years in other European. US and Japanese cities. This is a reminder though that London means an enormous amount to her, not least because it was where, in 1969, she met her future husband John Lennon with whom she memorably collaborated in ventures including recording with him as a duo in the Plastic Ono Band.

Yoko celebrated her 91st birthday on February 18, 2024, four days after the Tate’s grand retrospective-plus opened. She lives these days on a large farm she bought with the ex-Beatle in New York State, having late last year left her Manhattan residence, sadly the scene of her husband’s murder in 1980.

She is a reminder that you don’t always need large canvases or flamboyant gestures to make an impact in art.

She is a pioneer – in her initially minimalist and unhurried style – in conceptual and participatory art, film and performance, a celebrated musician, and an indomitable campaigner for world peace. Spanning seven decades of continuous multidisciplinary practice, Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind traces how she became a lodestar within contemporary culture. Her practice is very much a mixed bag, a description that the title of one of her early sights Bag Piece suggests.

Conceived in close collaboration with her studio, the panoramic survey gathers more than 200 works including haiku-like injunctions for delicately opening the mind, and much other creative endeavour, especially from the formative 1960s.

From the beginning, Yoko reached beyond the dominant art frameworks, seeking to stimulate and unlock minds and imaginations. The exhibition title is taken from her Music of the Mind concerts and events in London and Liverpool in 1966 and 1967. The whole is an ode to Ono that reflects her concept of silent music, that is, to produce sound in the listeners’ fancy. Trained in classical music, Yoko in 1966 explained her concept: “When a violinist plays, which is incidental: the arm movement or the bow sound [?]… I think of my music more as a practice (gyo) than a music. The only sound that exists to me is the sound of the mind.”

A patchwork of radical ideas is variously expressed in poetic, humorous and profound ways. On the website Imagine Peace, she has an article from 1971 entitled What is the relationship between the World and the Artist? “Violent revolutionaries’ thinking is very close to establishment-type thinking and ways of solving problems. I like to fight the establishment by using methods that are so far removed from establishment-type thinking that the establishment doesn’t know how to fight back.”

So ostensibly simple are her projects that she has been called pretentious by some critics; but she dismissed such taunts by asserting that “art is not a special thing. Anyone can do it… if everybody were to become an artist, what we call Art would disappear.”

The exhibition underlines that her trajectory was set when in 1964 she joined in artists’ protests ahead of that year’s Tokyo Olympic Games. The artists performed in public in the Japanese capital to disrupt what they called the “superficial happiness” in society. Leaving flowers on the street, Yoko’s contributions were subtler than the sometimes-destructive actions of her male companions. On the roof of a gallery hired by independent artists, she acted out what she dubbed Morning Piece, selling shards of glass from a broken bottle. Each piece was labelled with a date from the past or future and a time of the morning (“until sunrise,” “after sunrise,” or “all morning.”) In New York the following year, she presented Morning Piece on the roof of her apartment.

Fifty years later, she renamed the project as Morning Peace saying of the shattered glass “You can see the sky through it” to experience something as simple and universal as the dawn.

Film and stills from Ono’s arresting performance work, Cut Piece, make for one of the shocks encountered shortly after entering the Tate exhibition. The piece was staged in 1964 and raised among the viewers disturbing moral questions. Men and women in an audience were invited to cut away at her chic costume with a pair of tailor’s shears while she knelt uncomplainingly. She was impassive throughout except for a wince and slight eye-raising when a man sliced off a large piece of the material to expose her underwear. The manifestation has been variously interpreted but could be seen as the embodiment of taking advantage of a vulnerable woman.

This was 10 years before Marina Abramović echoed the format in her Rhythm O by opening herself to humiliation, sitting at a table on which were scissors, a gun, a scalpel, a rose, a whip, and other objects for an audience to use as they wanted. The Serbian artist has since been at the forefront of this genre of personal contact.

Continuing to upend convention, Yoko has unceasingly used her art and global recognition to advocate for peace. She continued to write ‘instruction pieces’ – short, lyrical sentences asking people to imagine, experience, make or complete a work. Some are a single verb, and some are encouragement to an activity, cerebral or otherwise, like ‘Listen to a heartbeat’ and ‘Step in all the puddles in the city.’ There are imaginary exercises like ‘Painting to be Constructed in your Head’. All this might be difficult to convey in a physical exhibition, but Ono’s collaborators and Tate’s curators manage to render how important to the irrepressible Yoko are such interventions.

There are previously unseen photographs showing her first ‘instruction paintings’ at her loft studio in New York – where she and composer La Monte Young hosted experimental concerts and events – and of her first solo and low-key exhibition during the hot summer of 1961 at the AG Gallery of Lithuanian American artist George Maciunas (1931–1978) in Madison Avenue. There, she spoke most of her instructions, inviting viewers to complete the paintings. Maciunas founded an international network of artists, named Fluxus after a magazine which featured musicians and artists close to avant-garde composer John Cage. Maciunas said that Fluxus sought to promote a revolutionary flood and tide in art, a democratic form of creativity that was open to anyone. This was in line with Yoko’s vision, although she was not formally a member of the movement.

Soon after the AG exhibition, Yoko pinned up at a Tokyo exhibition more than 30 instructions for paintings, without accompanying canvases. Typed up, these instructions were later compiled in her self-published anthology Grapefruit (1964), extracts from which are in sheet-by-sheet formats along some of the Tate walls. Why grapefruit? Yoko loved the fruit as a child and sees it as a spiritual hybrid between East and West.

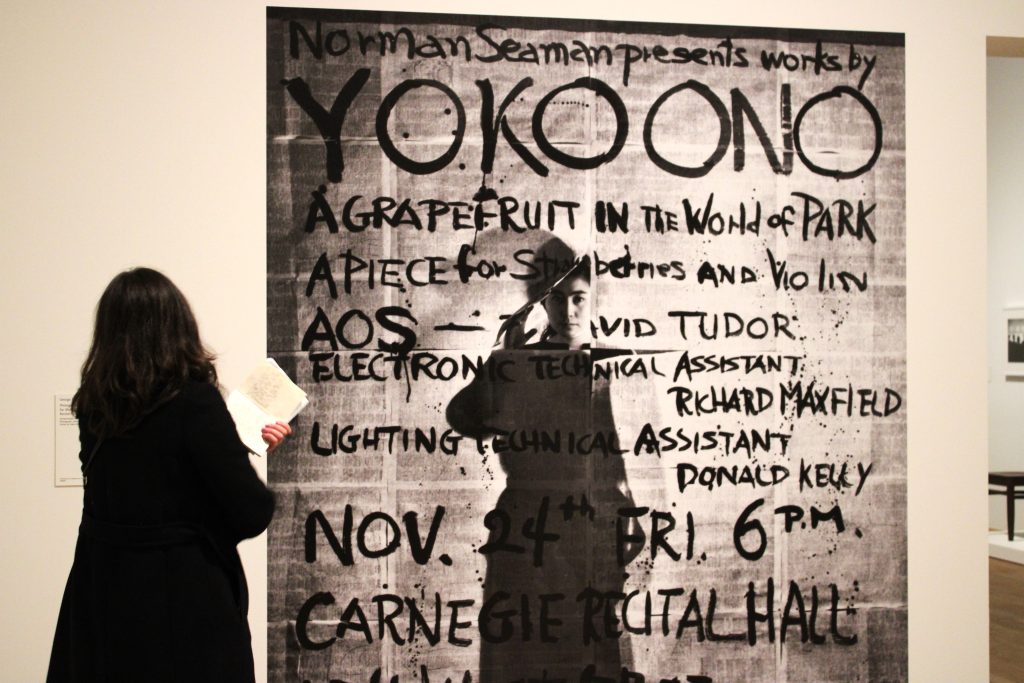

There are posters for AOS – To David Tudor, an ‘opera’ conducted in darkness, illuminated only by matches and torches, and A Grapefruit in the World of Park, a poem-like performance based on a 1955 story she had written, which she read on stage while some 20 artists, composers, musicians, and dancers followed her instructions, laughing and playing atonal music. In the original story, a group of characters discuss what to do with an unwanted grapefruit, before peeling and eating it.

In Bag Piece from the same era, gallery visitors are invited to enter black cloth bags and follow her instructions, and in the next room to mix and draw their shadows in Shadow Piece, an idea dating from 1963. Shadow Piece tells people to “Put your shadows together until they become one” and judging by the reactions, it’s good fun.

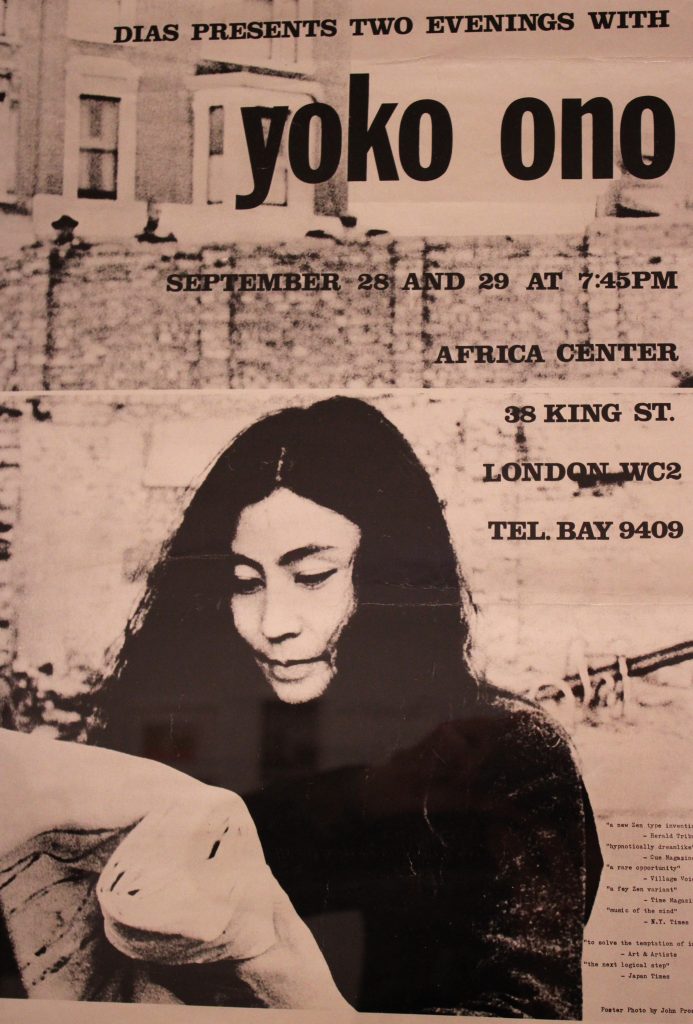

Yoko was invited to London in 1966 to take part in the Destruction in Art Symposium, a month-long series of concerts, talks, events and performances, mostly at the Africa Centre in Covent Garden. She had intended to stay briefly in London but became involved in the countercultural scene.

This led to exhibition offers, the first of which was Unfinished Painting & Objects at the Indica Gallery, where she met John Lennon. He was intrigued by Painting to Hammer a Nail, for which visitors were invited to bang a nail into a white panel to help cover the surface with nails. The banging heard throughout the Tate’s hall is a reproduction of the performance piece – pick up the hammer and have a go! Lennon told her he would use an imaginary nail, a remark that chimed with her, and which was to have historic consequences…

Installations from Yoko’s exhibitions in London feature, include the affecting Half-A-Room, a living room in which just half of each domestic and personal accoutrement is shown – bookcase, chairs, shoes etc, possibly symbolic of an emotional schism.

Yoko was meanwhile preparing for Wrapping Piece which was to cover in cloth the famed bronze lions in Trafalgar Square (rare photos of this event, for which police permission was granted, are shown), although she was not the first to stage such wrapping acts on a grand scale: for instance, the Paris-based couple Christo and Jeanne-Claude had started on that route years before.

Over an hour long and part of her peace campaign, Yoko’s once -banned Film No. 4 (Bottoms) of 1966-7 is based on – horrors! – close-up shots of bottoms. Her outlandish score begins with the instruction: ‘String bottoms together in place of signatures for a petition for peace.’ The bottoms footage was filmed in the West London home of an art dealer. The soundtrack has interviews with the participants who tell why they took part. The British Board of Film Censors banned the work after it was shown at a private viewing, which prompted the Royal Albert Hall to cancel a screening, deeming it ‘not suitable for public exhibition.’ There are photos of Yoko protesting with daffodils outside the Board’s offices.

Lennon and Ono were married in 1969 in Gibraltar and staged week-long Bed-In for Peace campaigns in Amsterdam and Montreal. They wanted to do the same in New York, but Lennon was refused a US visa because of his earlier conviction in London for marijuana possession. He said later of the Bed-Ins: “I participated almost like a spectator because it was Yoko’s way of demonstrating.” Peace campaigners and activists were among those invited to join the couple in their hotel rooms. At their bedside in suite 1742 in the Queen Elizabeth Hotel in Montreal there were American and Canadian reporters; comedian and musician Tommy Smothers; singer Petula Clark; beat poet Allen Ginsberg; psychologist and drug guru Timothy Leary; civil rights activist and comedian Dick Gregory; Radha Krishna devotees; and others. There, the couple recorded Give Peace a Chance which was soon adopted by protesters against the American war in Vietnam.

A highlight of the spectacle Bed Peace (a Bag Productions film) is John and Yoko calmly batting away the jibes of the self-important satirical cartoonist Al Capp (1909-79) who introduced himself with the words “I’m a dreadful Neanderthal fascist. How do you do?” and later sarcastically congratulated John and Yoko over their picture standing naked for their Two Virgins album cover. Capp becomes increasingly discomfited. He had once been a liberal but had become bitterly conservative.

Asked about their unusual strategies, Yoko says: “We are using our money to advertise our ideas so that peace has equal power with the meanies who spend their money to promote war.” The public poster campaign WAR IS OVER! (if you want it) appropriated the language of advertising. Acorns for Peace saw Ono and Lennon send acorns to world leaders.

Popular with visitors is White Chess Set – a ‘game’ first realised in 1966 designed to illustrate Yoko’s anti-war stance. It has white pieces only on a board of white squares, with the instruction ‘play as long as you can remember where all your pieces are.’ A supposed version of chess that does away with confrontation, perhaps.

Yoko refers repeatedly to the ‘sky’ as a metaphor for peace, freedom, and unlimited potential. This has its origin in her evacuation to the countryside during the bombing of Tokyo in World War II. She and her younger brother found solace in the sky as one of the few beautiful things at the time in her life. Her book Grapefruit urges readers to view the sky or engage it as a musical instrument: “Painting to See the Skies. Drill two holes into a canvas. Hang it where you can see the sky. (Change the place of hanging. Try both the front and the rear windows, to see if the skies are different.)” Again, more than 50 years ago in London, she proposed SKY T.V.: “a TV just to see the sky. Different channels for different skies, high-up sky, low sky, etc.”

More recently, from the ever-flowing river of her mind, Yoko’s project Add Colour (Refugee Boat) which stems from 2016 invited people to draw words in blue on the white gallery walls, the floor and a white replica boat while reflecting on global issues of crisis and displacement. Yoko’s appeal reads: “Just blue like the ocean. You are invited to contribute your hopes and beliefs in blue and white chalk.” This is repeated at Tate: within a couple of days there was hardly a centimetre of the boat and the room untouched by slogans about Palestine and the gamut of 2024 concerns. Yoko conceived the work after being moved by press coverage of the thousands of refugees risking their lives to reach by sea what they believe to be safe countries. The exhibition label quotes the UN Refugee Agency prediction that, in 2024, the number of people world-wide forcibly displaced and stateless will rise to more than 130m.

The exhibition concludes with more from her sympathetic imagination: Yoko’s installation My Mommy Is Beautiful, first realised in 2004, featuring a 15-metre-long wall to which visitors can attach photographs and personal messages about their mother. The Wish Tree, originating from 1996, greets allcomers at the entrance to the gallery, inviting them to make individual wishes for peace.

Throughout her long career, Yoko Ono has been steadfast in her aspiration for people to share a better world. Now the question is how the desire can be transformed into materiality amid the intensifying global horrors of conflict and hunger. She famously said: “A dream you dream alone is only a dream. A dream you dream together is reality. Whisper your dream to a cloud.”

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind is supported by among others investment banker and philanthropist John J Studzinski CBE. The exhibition is organised by Tate Modern in collaboration with Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf. It is curated by Juliet Bingham, curator of international art at Tate Modern and Patrizia Dander, head of the curatorial department of Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, with Andrew de Brún, assistant curator of international art, Tate Modern, and Catherine Frèrejean, assistant curator of Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen.

Captions in detail:

Cut Piece 1964. Performed by Yoko Ono ‘New Works by Yoko Ono,’ Carnegie Recital Hall, New York, March 21, 1965.

Photograph conceived by George Maciunas as a poster for Works by Yoko One, Carnegies Recital Hall, New York. November 24, 1961. Poster by Yoko Ono.

Yoko One on poster for Destruction in Art Symposium in London. Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

Yoko Ono and John Lennon during Bed-In for Peace, Amsterdam, 1969. Courtesy Yoko Ono. Photograph by Ruud Hoff. Image: Getty Images/ Central Press/ Stringer. © Yoko Ono.

Add Colour (Refugee Boat) by Yoko Ono in Tate installation, detail with visitors’ graffiti.

Close-up of Add Colour (Refugee Boat) by Yoko Ono in Tate installation with visitors’ graffiti.

White Chess Set, first realised in 1966, in Tate installation.

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind is at Tate Modern, London, until September 1, 2024.