Dr. James Lewis

Half a millennium on, the calamitous East Asian War of 1592-98 reverberates in international relations, historian James Lewis tells London meeting of Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation, By James Brewer

It was the equivalent of one of the great wars that originated in Europe and unleashed huge destruction in the 20th century, but the East Asian War of 1592-98 is to most Westerners just a footnote in history.

Dr James Lewis, lecturer in Korean history and Fellow of Wolfson College at Oxford University, told an audience in London of the need for greater understanding of the epic nature of the seven-year conflict, which continues to impact relations between the nations involved – Japan, China and Korea – today. After all, these are today the world’s third, second and 13th (South Korea) biggest economies. Dr Lewis was speaking at a meeting of the Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi, referred to by some as the Napoleon of Japan, set out to conquer Korea, China, India and then the rest of the world, said Dr Lewis, who has edited a new book, The East Asian War, 1592-1598: International relations, violence, and memory (published by Routledge). If victory against China had been the order of the day, Hideyoshi would have transferred the Japanese Emperor to the throne in Beijing, while Hideyoshi himself would have gone to Ningpo to plan the invasion of India and beyond. In reality, there was only humiliation: the Japanese armies, worn down by attrition and stymied at sea by a brilliant Korean naval commander, had to withdraw and got nothing except what they pillaged from Korea. Hideyoshi (1536-1598) had to reduce his goals to what he saw as the permanent seizure of Korean land.

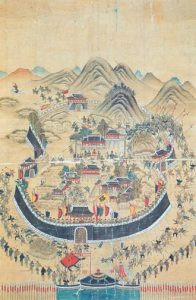

A Depiction of Patriotic Martyrs at Tongnae (National Treasure No 392) painted by Pyŏn Pak, Courtesy of the Korea Army Museum, Korea Military Academy.

With contributions from 17 Japanese and Korean experts, the 402-page book presents a comprehensive analysis of the war, which transformed relations between the three nations, and its military, political, social, economic, and cultural aftermaths.

The aim is to deepen insights into the strategic concerns that continue to resonate in the region. “I argue that the history of East Asian relations is still largely unknown and a mystery to the West where scholars are failing to alter their European-derived theories, ” said Dr Lewis.

He compared the conflict with the great international wars of Europe and continental Asia. It is a war that has many names (including the East Asian War, the Hideyoshi invasions of Korea, and the Seven Year War), but has received little attention in Western scholarship, he said. By contrast, the subject is firmly on the curricula of schools in the region.

It was the only massive slaughter on an international scale in northeast Asia between 1400 and 1894, and involved the largest overseas landing in world history up to that time.

Numbers of combatants may have reached 500, 000, and Korea was devastated. Japan had been in the depths of civil conflict between competing warlords, until guns changed the dynamic and Hideyoshi united the country. At the same time the Japanese were active all over the western Pacific, “so I would like to ask you to throw away the notion that Japan had been isolated, ” said Dr Lewis. The 16th century was a piratical time throughout the region. Japanese pirates – in effect licensed by the regime – from the Japanese islands and freebooters who would put on Japanese garb had long raided the Korean and Chinese coasts. One week they would be pirates, the next appear as successful traders.

In 1523 the Japanese had lost their tally trade (a system under which the Japanese and the Chinese during the Ming dynasty engaged in official trade: the tally was a document which Japanese ships would carry to Chinese ports to demonstrate that they were legitimate merchants). The breakdown came with a row over the “imposter envoys” who claimed to be bona fide businessmen, and who had plundered a ship of the powerful Hosokawa clan in Ningpo harbour and gone on to ravage the Chinese countryside.

Man in Korean Costume, about 1617. Black chalk with touches of red chalk in the face. By Rubens. J Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Hideyoshi viewed Korea as Japanese territory that was in revolt, but Dr Lewis sought to dispel the ‘myth’ that Japan possessed any part of the Korean peninsula, at that time under the Chosŏn dynasty. The Japanese landed at the port of Pusan with a force of 158, 000 troops and pushed northwards, to the Chinese border.

Dr Lewis drew attention to a painting from the Korea Army Museum that is used as an illustration for the front cover of his book. This is “A Depiction of Patriotic Martyrs at Tongnae” painted by Pyŏn Pak in 1760. The painting shows the Tongnae Magistrate Song Sanghyŏn and people inside the walled city of Tongnae in Pusan harbour resisting the 1592 Japanese invasion.

“Note the defenders on the walls with bows facing the Japanese with rifles, the magistrate in the centre maintaining his calm as the invaders threaten him, the Korean general in the upper left fleeing, and the women who have climbed on to the roofs hurling tiles down on the Japanese, ” said Dr Lewis. “The women with roof tiles are the most effective Korean defence depicted in the painting.” He added: “The Japanese thought a lot of the magistrate as a worthy opponent, although he was killed on the spot.”

There was a second invasion in 1597 (a year in which, incidentally, Hideyoshi executed foreign missionaries and their Japanese converts).

Japan did at first occupy the Korean Peninsula, capturing Seoul and P’yŏngyang, but were thrust back by Chinese battalions which came to the rescue of the Koreans, and the Chosŏn navy played havoc with Japanese supply fleets.

This was where Admiral Yi Sun-sin – little known outside Korea to this day – came in. His record is remarkable, including his concepts of superior ship design and his military talents. “He is a national hero, bar none, in Korea, ” said Dr Lewis, adding that “the man was a technical genius: the Japanese navy revered him.” Later historians claimed he had a better grip on battle tactics than even Admiral Nelson. He was never defeated in the 23 battles he fought at sea, and lost only two ships.

His great technical achievement was the Kŏbuksŏn ship, known from its appearance as the Turtle Ship. It was probably the first ironclad warship in the world, with substantial firepower and manoeuvrability. It could sink large numbers of enemy vessels, and was a morale-booster for Korean sailors in the face of the mighty Japanese navy, which in fact was handicapped in its choice of weaponry and lack of cannon.

The Kŏbuksŏn had a covered deck, which was the turtle’s ‘back’ made from planks covered with iron spikes to make it impregnable to boarders. The spikes were disguised by straw matting, and would impale any hostile intruder.

This was what kept the Japanese sea-power at bay and wrought havoc on the logistics network that was needed for the longer-term goal of invading China. The Japanese were also caught out by the waters off the south coast of Korea which are very shallow, with lots of islands. “If you do not know your way around, you are in trouble, ” said Dr Lewis.

This maritime success ran counter to the Japanese view that the Koreans were incapable of defending themselves – “culturally superior, but militarily inept, ” as one cynic had it.

“After one year, the Japanese losses were staggering, from battle fatigue as well as disease, ” recounted Dr Lewis. A second invasion in 1597 met a similar fate to the first, and on the death of Hideyoshi the following year, Japanese forces in Korea were ordered by the successor regime to return home.

Koreans have bitter memories of this period. The country had lost thousands upon thousands of civilians to war, disease and famine, the Japanese had looted and pillaged extensively, and the Chinese had extracted local supplies from a war-ravaged land.

Japanese troops kidnapped artists, musicians, scholars, potters, weavers, paper-makers and printers. In particular, styles of pottery were appropriated by Japan from their Korean captives, and the knock-on effect was the export of huge amounts of porcelain to Europe, some of which can be seen in the great houses of England today. Moveable metal type had been developed by the Koreans, possibly as early as the 13th century, and the Japanese toyed with adopting it but preferred woodblock production.

China weathered the financial burden of this and other wars in the 1590s, but within a few short decades the Ming Dynasty was toppled by the Manchus, who themselves sent two punitive expeditionary forces into Korea in 1627 and 1636. Eventually the Qing dynasty took over in China and trade relations between the three nations were repaired.

Hideyoshi is seen as having a scorecard of two sides. Despite the war he enjoys respect. “He is a hero in Japan not because of the war, which was a major mistake, a disaster, ” said Dr Lewis. “He is a hero in that he came from nowhere, as the son of a peasant, rising from a foot soldier to the most important man in Japan, with extraordinary accomplishments, eschewing the atrocities committed by predecessor lords.” He had unified Japan after a century of civil war, disarming the peasantry and bringing peace to the countryside. Hideyoshi encouraged landscape gardening, the tea ceremony, calligraphy, painting, and architecture, including the construction of Osaka Castle.

His military strategy was to appear before his opponents with overwhelming forces and “make them an offer they cannot refuse.” He absorbed his enemies rather than conquering them. But if you rebelled against him, you would be destroyed. He had built up a navy of 2, 000 ships. It is hardly surprising that he is of endless interest today to NHK broadcasters.

It was largely as a result of the war that Europeans ‘discovered’ Korea, shown for instance by the painting Man in Korean Costume of 1617 by Peter Paul Rubens (J Paul Getty Museum) who thus introduced a new part of the ‘distant’ Far East to the West.

Despite subsequent major conflicts, the East Asian War showed the importance to regional stability of the subtle relationship of Korea to both China and Japan, issues that “I believe are still hotly relevant today, ” said Dr Lewis, who is president of the British Association for Korean Studies.

The East Asian War, 1592-1598: International relations, violence, and memory, by Dr James Lewis, is published by Routledge. Details at www.routledge.com